The Liberty Truck of WWI

The “Liberty” truck of WWI would lay the groundwork for the future of truck production.

It is not often that plans to design and develop a military vehicle or aircraft by a consortium of several or more companies actually succeed, but occasionally such an idea does work. One such example is the American-designed and built so-called “Liberty Truck”, which entered service during the later stages of World War I and went on to be used not just by the American Army, but also the Allied armies of France and Britain.

By 1917 the war in Europe had entered its third year and there was still a stalemate along the front line, which extended almost 500 miles from the North Sea coast of Belgium down to the Swiss border — an area known as the “Western Front”. Following a series of German acts of aggression, which included attacks against American vessels, the U.S. was provoked into entering the conflict. On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson requested a special session of Congress to declare war against Germany. On April 6, the Senate voted 82 to 6 to pass the resolution, which was followed by the House voting overwhelmingly 373 to 50 in favor of the act.

According to figures from the US Army Center of Military History, the regular standing army at the time numbered almost 130,000 men, with another 181,000-plus troops in the National Guard. By the end of the war in November 1918 the numbers of men mobilized would reach over 4.17 million, of which nearly 2 million would be sent to France.

Only a year before, the U.S. Army had some 600 motor vehicles in its inventory and their experience in recent military campaigns was limited to service along the Mexican border against rebel insurgents. Over the next 18 months the number of motor vehicles in service would increase to 82,500 through the combined output of the American auto industry — a demonstration of industrial capability that would be repeated 25 years later when the country was forced into another war.

Some American companies, such as the Peerless Motor Company of Cleveland, Ohio, had been supplying trucks to the British Army since 1915, and by 1918 that figure would reach 12,000 vehicles from just this single manufacturer. When the U.S. joined the fray, the American Army would require vehicles of all types as quickly as possible and would have to take priority over other end users.

At the time the U.S. entered the war, the American military was using some 294 different types of trucks, of which 213 were produced by American companies. Between them, the various builders used no fewer than 60,000 different parts which were of “non-standard”’ design between types of vehicles. Obviously, this was not efficient and something had to be done. The initiative was taken by Captain W.M. Britton of the US Army Corps of Engineers. He recommended to General G. Henry Sharpe that a fleet of trucks be created based on a standardized design.

Sharpe agreed and in July 1917 a meeting was convened for Captain Britton, accompanied by Major Charles Bryant Drake of the Quartermaster Corps. They met with representatives from the leading truck manufacturers of the day to discuss their idea for developing a uniform vehicle design which used common components that were interchangeable. The two officers were able to convince members of the Society of Automotive Engineers to compile a report that could be presented to the Army’s General Staff. The SAE was an organization involving leading vehicle manufacturers to engage in a “…free exchange of ideas” and included the likes of Henry Ford, Orville Wright, Thomas Edison, Elmer Sperry and Andrew L. Riker. The plan for standardization was eagerly endorsed by everyone involved.

John Norris

Drake was a highly decorated and experienced field officer, having served on campaign in the Philippines in 1904. Only a month after the meeting with the SAE he was tasked with organizing a new unit known as the Motor Transport Corps, separate from the Quartermaster Corps. It came into being later in August and would remain as a unit in its own right until 1920, when the troops and equipment reverted to being part of the Quartermaster Corps once again. Serving in the Quartermaster Corps, he would have known the importance of moving supplies as fast and reliably as possible and that would mean motor transport. No doubt he would have been aware of the fact that during the period between April and December 1917, the total supplies dispatched to France amounted to 484,550 tons. He would have also guessed correctly that this figure would increase and with the MTC, and it did — so much so that by the end of war the average monthly cargo being sent to France was 426,000 tons, all of which had to be distributed from railheads. It was a task that would only be possible with trucks.

The vehicle which emerged from the SAE report become known as the Class B Standard Military Truck, but was referred to as the “Liberty Truck”. It was the first properly standardized vehicle to be used by the Army and had been achieved by joint cooperation of the Army’s Quartermaster Corps and a consortium of 15 civilian companies that would build the vehicles using the best technology available at the time. Among those involved were the Bethlehem Motor Truck Company, Diamond T Motor Car Company, Kelly Springfield Motor Truck Company, Velie Motors Corporation and the Republic Motor Truck Company. Between them they would produce 9,364 vehicles of which around 7,500 were shipped to France.

Within 10 weeks of the decision to accept the design, the first two prototype vehicles were ready for field trails. They had been built by the companies of Gramm-Bernstein of Lima, Ohio and Selden of Rochester, N.Y.. Both of the companies were in line to produce 1,000 Liberty Trucks. The vehicles were driven more than 400 miles to the test ground at Washington D.C., on Oct. 19, 1917. There, they successfully completed the trials in front of Secretary of State for War Newton D. Baker, who approved of the design. The first production models were rolled out three months later in January 1918.

Contracts for more than 43,000 of the new trucks were placed, but by the time of the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918 the 15 companies involved had turned out 9,364 between them, ranging from just five from Packard in Detroit, to 975 delivered by Pierce-Arrow Motor Car Company of Buffalo, N.Y. From this figure around 7,500 would be sent to France and more than 51,500 sent to American forces.

The relatively low delivery figures were not due to poor productivity, but rather from the late arrival of vehicles in France. The first batch of Liberty Trucks sent overseas did not reach France until October 1918, at a time when American forces were engaged in the massive Meuse-Argonne Offensive, between Sept. 26 and Nov. 11, 1918. This operation pushed the Germans back and contributed to bringing an end to the war only weeks after the vehicles had been delivered. When the fighting stopped, all outstanding truck deliveries were canceled, leaving the group of 15 companies producing Liberty trucks with a surplus on their hands. But not for long.

Vehicles used by the American military were given categories to identify their load-carrying capacity. For example, the “AA” and “A” Classes could carry up to 1 and 1.5 short tons, respectively. The “B” Class was rated to loads of 3 to 5 short tons and it was into this heavyweight category the new truck, now being referred to as the “Liberty”, was consigned. One of the first units to receive Liberty trucks for service was the 3rd Infantry Division. The exact number of trucks used directly in supporting frontline units is unknown, but the supplies carried by those that did would have provided much-needed support where it was most needed.

In the immediate post-war years, new outlets were found to sell off those Liberty Trucks. Among the recipients were Polish forces engaged in fighting to secure the country’s borders against Russian forces between 1919 and 1921. Trucks already in France were sold off to civilians and put to use in various roles, including transportation. Likewise, vehicles coming from the factories were offered to civilian customers for use on farms, removal firms and a range of transportation roles. One of the last military duties for some Liberty Trucks was serving with troops of the American Expeditionary Force deployed to Siberia between 1918 and 1920. A few survived to remain in service beyond the end of the war and some were still operational into the 1930s.

The Liberty Truck was produced in two series and incorporated differences which were important to improving the overall performance of each vehicle type. For example, the First Series had electric lights throughout, dual ignition and magneto system with independent spark plugs. The Second Series had improvements made to the oil system, and a reserve fuel tank was mounted under the passenger seat with a manual pump for transferring fuel to the man tank. They two versions remained largely the same externally, with the driver’s cab being open apart from a canvas tilt cover supported on a collapsible frame to protect the driver.

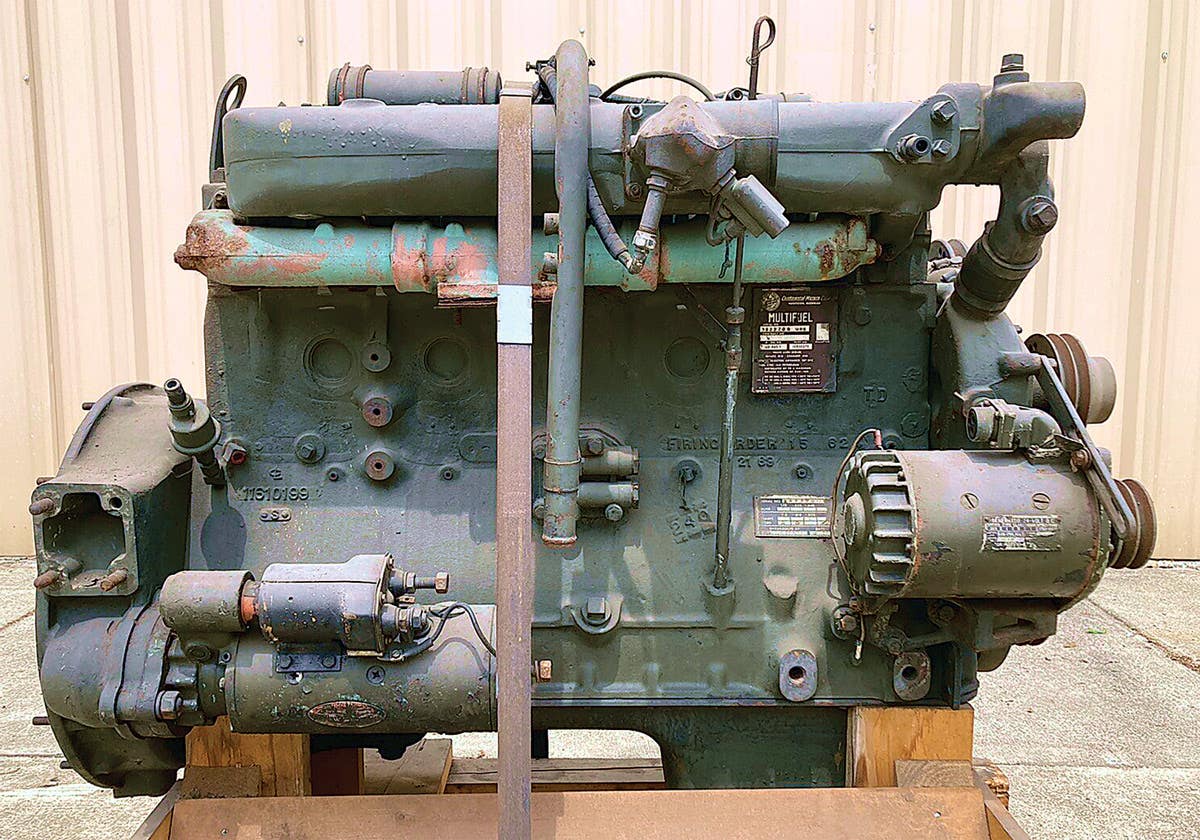

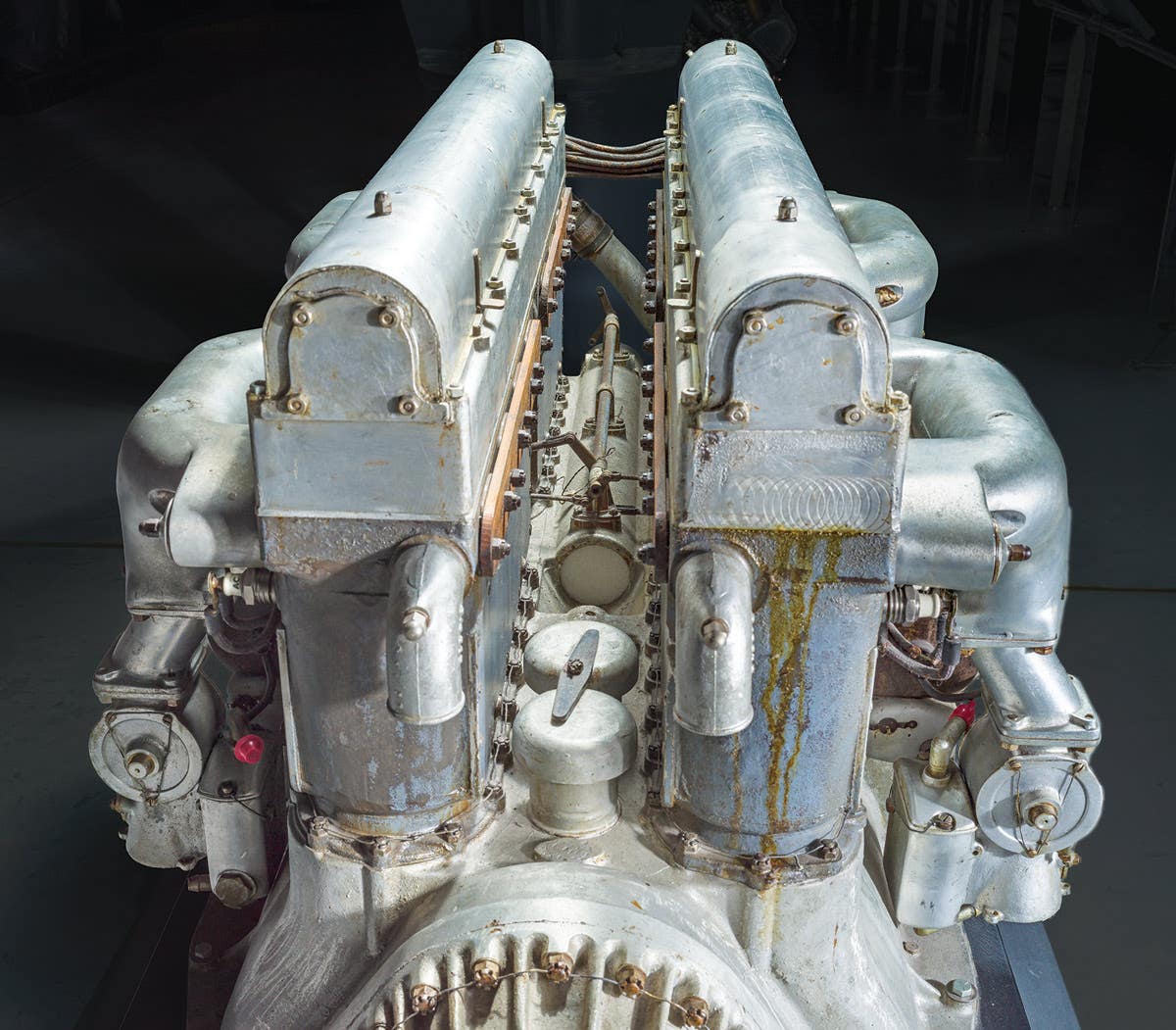

The engines were supplied by a collaboration of five companies, including the Hercules Engine Company, Wisconsin Motor Manufacturing Company, and Waukesha Engines. Fuel consumption varied between 3.5 and 7 miles per gallon, depending on operating conditions.

A post-war variant — a 5-ton rated “Class-C” 6-wheeled truck based upon the Class-B Liberty design — was considered. It would have had an extended rear cargo bed and been fitted with twin rear axles, a design which other types of truck had proved to be practical. However, in the end, the design was never pursued.

There are a small number of known surviving Liberty Trucks, probably as few as 16, to be found in aviation and military museums across America. The National Museum of the USAF in Dayton, Ohio, has a Second Series example, and The Oregon Military Museum has a Series One.

There are perhaps only four in working condition. An example of a Series One, sometimes referred to as a “First Series”, is held by Ian Morgan who resides in Dorset, England, where for the past couple of years he has exhibited it at the annual Tankfest Show. The truck has taken part in a display showing WWI vehicles, to the delight of the spectators on hand.

Morgan obtained his truck from a source in France. He has spent a considerable amount of time restoring it a high level of original specifications. When Morgan took ownership more than 10 years ago, the truck lacked the rear wooden bodywork, but using a set of original plans he was able to rebuild the body using the correct type of wood. In 2015 he replaced the seats and later the canvas tilt over the driver’s cab

In addition to Tankfest, Morgan enjoys taking his Liberty Truck to participate in other special events, including memorial commemorations in France and Belgium, where it always attracts much attention.

John Norris

John Norris