Tech Tips: With Steve Turchet

Advice on restoring a DUKW, trouble-shooting a radiator problem on a M151, helping out an overheating M38A1, and more, from “Tech Tips” expert Steve Turchet.

HOT DUCK

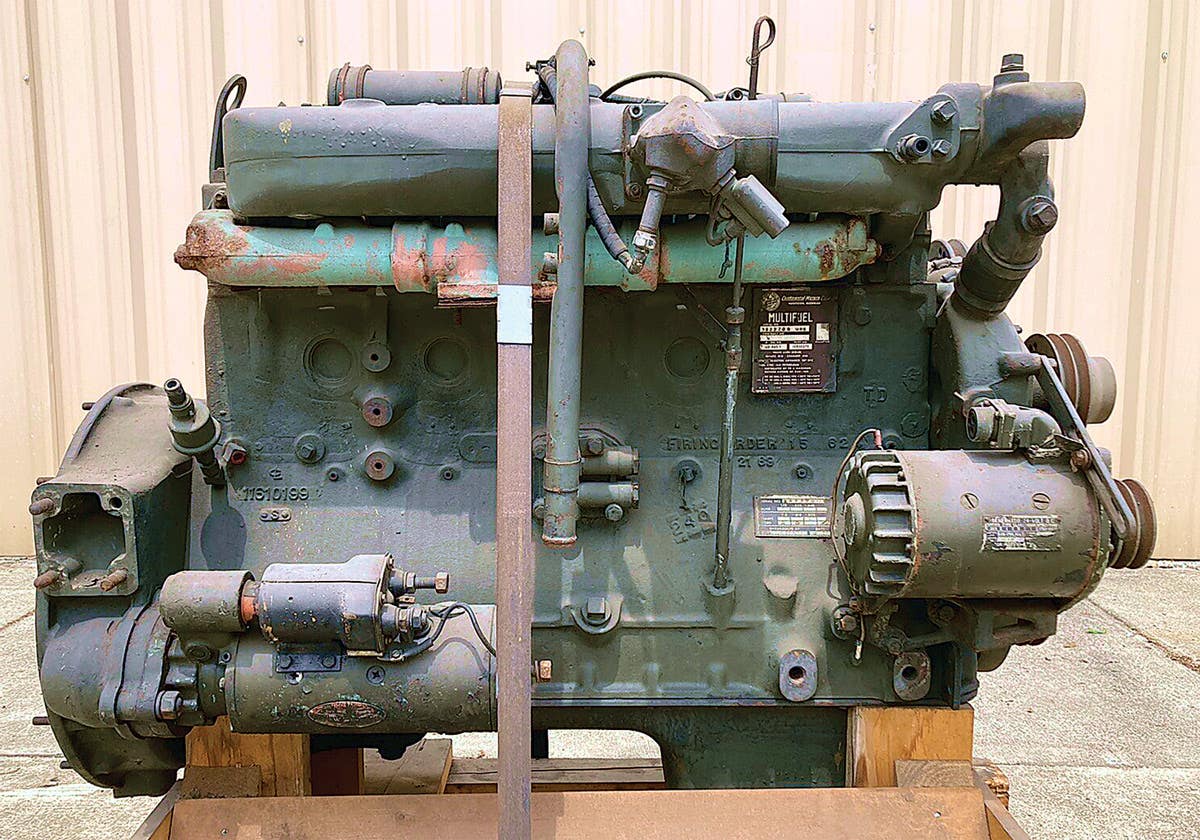

I recently bought a running and swimmable DUKW. It belonged to a marina but was garaged for many years. The data plate shows it was built in 1943. It is in good condition except for surface rust. I intend to restore it, but I worked on it for a week to go out on the lake to see what it would do. It ran very well and I was surprised at how well it ran in the water. But it seemed like the exhaust manifold got dangerously hot. I noticed there were shutters in the drivers compartment. Should these have been opened?—Ron Reeves

Congratulations on your new quacker. I assume you’re going to buy manuals before starting your restoration? Among these should be the operations manual. A DUKW has a pusher fan on the engine. Air is pulled in through the grating behind the driver’s compartment, pushed forward through the radiator into the bow compartment, then exits through the screened openings on the outside of the driver’s compartment.

Unlike a land vehicle driving down a road, there isn’t much air flow over the engine so a DUKW’s exhaust manifold becomes very hot. In fact, fledgling DUKW drivers on night training exercises were often startled to see the manifold glowing red through openings in the floorboards. This is normal, though one should avoid lugging the engine. A manifold vacuum gauge is a useful addition to any DUKW, showing how hard the engine is working. The greater the load, the hotter the exhaust manifold becomes, and gasoline engine exhaust can get hot enough to melt lead. The shutters you described are merely to heat the driver’s compartment and have no effect on engine temperature.

RADIATOR R.I.P.

I have a 1967 M151. The radiator is probably original because several tubes have started leaking. I plan to have it re-cored as soon as I can afford it but I would like to know if you think that using a stop leak is safe for the engine? If so, do you have any recommendations?

No radiator lasts forever and will eventually have to be replaced or rebuilt. One can usually get by for a while, or fix a minor damage leak, by using a good quality stop-leak product. Most of these work basically like a blood clot, solidifying where engine coolant meets air, such as a split in a radiator tube, or a crack in an engine block or cylinder head. Unless grossly misused, most stop-leaks can’t damage an engine.

While one usually gets what one pays for in life, I’ve found that high price doesn’t always guarantee effectiveness with stop-leak products. Results also vary with the type, location, and seriousness of the leak. I once used something called KW Block Seal in a GMC engine with a very badly freeze-cracked block and put thousands of miles on the truck with no problems. However, radiator tubes expand and contract a lot, so are often harder to seal.

About the only product I’ve never had good luck with is “Bars Leaks.” Other than this, my advice is to carefully read the product’s label and follow the manufacturer’s instructions, especially in regard preparing the cooling system, whether or not to flush it first, and how much product to use depending upon the capacity of the system. After all, the manufacturer wants it to work so you’ll buy something else from them.

HOW HOT IS IT?

I have a 1956 M38A1. What is the correct thermostat to use? They come in 160°, 180°, and 190° (F) heat ranges—Donald Spencer

Many people don’t know that the heat rating on thermostats refers to when the thermostat begins to open. It has nothing to do with how hot or cold the engine may run. That depends upon many factors, such as the condition of the engine and radiator, how hard the engine is working, and the temperature of the surrounding environment. Installing a 160°F thermostat in your jeep is no guarantee that the engine would not run at 200°F if pulling a heavy load through a desert when the temperature of the air is 110° F.

Generally speaking, most older collector MVs, such as jeeps, MUTTS, M37s and M35s with cooling systems in good condition and used in average North American climates will benefit best from 180°F thermostats. For long hot summers or desert operation, 160°F would probably be better. On the other hand, when temperatures are consistently below 40° F, then a 190°F thermostat might work best.

By the way, removing a thermostat is no guarantee that an engine will run cooler. If fact, it may overheat because without a thermostat to regulate the flow, the coolant may circulate through the system so fast that the radiator doesn’t have time to cool it.

BUT I BLEW MY HORN!

Not exactly a tech question, but I respect your opinions. I’ve noticed that prices of surplus HMMWVs are dropping. This is probably because more are becoming available. I’m hoping that the price will keep dropping until I can afford one. On the other hand, I’m concerned that like the MUTT and the Gama Goat the government might decide that military Hummers aren’t “safe” for the public and start crushing them. Any thoughts.

There’s an old joke (usually sexist) about a motorist who ran into a tree. When asked what happened, the driver squalled, “It’s not my fault, I blew my horn!”

The U.S.A. seems, increasingly, a land of “It’s not my fault!” There was a recent lawsuit where a man hit a street lamp. Although convicted of drunk-driving, he sued not only the city for putting the street lamp where it was, but also the company that made the lamp! He didn’t win, but it seems more scary than funny that he (or his lawyer) thought he might.

In regard to your question, I would say that, just like the M151 MUTT and the M561 Gama Goat, military HMMWVs will probably be available to the public only until someone, though lack of driving skill and/or sloppy maintenance, has a serious accident and he or survivors, and/or attorney, manages to convince a jury that it was the HMMWV’s fault. If I wanted a HMMVW, I don’t think I’d wait and hope the price would drop into the range of an average M35A2 before buying one.

HMMWV UPGRADES

The U.S. Army is enhancing vehicle safety by installing five new upgrades to HMMWVs at forward repair sites. These include a fire suppression system, improved seat restraints, an intercom system, a gunner’s restraint, and single movement door locks.

While these upgrades will initially be installed in HMMWVs, the Army is adapting some of them to other medium and heavy tactical vehicles. Eventually, the entire tactical fleet will receive the fire suppression system. New gunner restraints and the intercom system will be installed on all vehicles with gun-mounted turrets, and most tactical vehicles will receive the new seat belts.

GREASE WHERE IT BELONGS

Jacking a vehicle’s front end off the ground by its bumper or frame so the entire front axle and both wheels hang down from their springs is the only way to be sure the springs shackle bushings are properly lubed. Why? Because if you lube them with the vehicle on the ground the grease can’t get into the upper part of the bushings because the vehicle’s weight is resting on them. It’s the upper part these bushings that wear the most. This procedure also applies to the rear spring bushings.

THINK BEFORE YOU JUMP

Using your vehicle, MV or otherwise, to jump-start another vehicle can be very hard on your generator or alternator unless it’s done right. An alternator or generator is not designed to charge a vehicle’s battery while the starter is cranking and drawing a lot of power.

If the other vehicle’s battery is dead, hook up your jumper cables—taking all the usual precautions—then run your engine at moderate RPM for at least five minutes to charge the other vehicle’s battery. Then, shut your engine off while the other driver cranks his.

Don’t let yourself be talked into running your engine while the other guy is cranking because “it saves time.” It might save him time, but that won’t help you if your generator or alternator gets fried!

Of course, you could remind the impatient fellow how long it would have taken for a tow-truck to get there if you hadn’t decided to help him.

JEEPERS-CREEPERS

I bought a 1944 Willys MB that has been in storage for over 30 years and appears to be all original. When going over the engine prior to starting it I noticed a fitting on the valve cover plate that isn’t connected to anything.

I can’t find any mention or a picture of a fitting like this any of my manuals and no one else seems to know anything about it. It is giving me the creeps because I don’t know how important it is. I don’t want to screw up the engine by running it with something missing.

Do you have any idea what this fitting is for and where it should be connected? It isn’t for the PCV valve because that is already connected like the manual says it should be. Could it be something for deep water fording? Thanks.—Russel Beck

Nothing to get creeped about. I suspect your Jeep’s valve cover plate is actually off a generator, possibly a PE95 10KW, which used MB/GPW engines. You can simply plug the fitting, or if restoring your Jeep you may want to get the correct cover.

HOW MANY HUMMERS?

Hello. I am new to the military vehicle hobby and I just discovered your excellent magazine. I want to buy a Vietnam M151as a first MV. I am also interested in HMMWVs but will have to wait until their prices go down before I can seriously consider getting one. This is not exactly a technical question, but do you have any idea how many HMMWVs the U.S. military has? When do vehicles get sold as government surplus? What makes the government decide to sell a vehicle? What has to be wrong with them?—Jerome Acton

Welcome to the military vehicle hobby! I hope you find your MUTT.

Current estimates are that the U.S. Military has about 350,000 ground vehicles in service. Of course there are many types, ranging from fully tactical (or combat) vehicles to ordinary civilian cars and trucks. One estimate is that about 140,000 HMMWVs are presently in service, but this figure includes many Hummers that aren’t actually drivable, have been damaged in various ways, and/or are parts vehicles being cannibalized to keep other HMMWVs running. Government contracts specified that HMMWVs would have a service life of 13 years, though most HMMWVs average about 17 years. When and why military vehicles are sold at government auctions or otherwise disposed of is one of the mysteries of the universe.

Interestingly, corrosion is one of the biggest reasons. The current official rule-of-thumb is that a vehicle is sold or disposed of when the cost of repairing it exceeds 65 percent of its original acquisition price; though many folks, especially military vehicle dealers, who frequent government auctions often tell tales of finding pristine vehicles with very little wear or damage. The actual decision to get rid of vehicles is usually made at individual military bases by those in charge of motor pools, so there are some mistakes... as well as a little hanky-panky at times.