Beware the “Devil” in the Details

“You should be a writer,” my Mom recently commented to me. I just rolled my eyes. It’s been a hectic few months since my Dad passed away, so maybe she…

“You should be a writer,” my Mom recently commented to me. I just rolled my eyes. It's been a hectic few months since my Dad passed away, so maybe she doesn’t remember what I do for a living—or maybe, she was just making a joke. Regardless of her current motive, I am willing to bet she doesn’t know how much influence she has had on my collecting and writing.

Patton’sBiography

When I was seven years old, I couldn’t get enough military history. War movies, toy soldiers, my Dad’s war stories. One day, in an attempt to gain my Mom’s attention long enough for her to look down from the sink of dirty dishes at the magnificent battle scene I had just drawn, I employed a new strategy. Rather than the frontal assault of, “Look at what I drew,” which could fall flat, depending on her mood, I held up the picture and said, “Someday I am going to be famous.”

That got her attention. She stopped scrubbing the plate, looked out the window in front of her, and asked, “Oh, how is that going to happen?” My seven-year old arsenal had expended its only round. “Umm…well. I don’t know, but I just am!”

I guess I had unknowingly created one of those Hallmark-esque, mother-son moments. She dried her hands, turned toward me, and crouched down to speak, “eye-to-eye.”

“You like history, John. Are you going to become a famous historian?” she asked. “What’s that?” was all I could muster.

“A person who looks at history—like the military history you enjoy—and figures out how to teach other people about it,” she explained.

“Would I have to be a teacher?” I asked. I had a notion what was involved in that since Mom taught high school math.

“Oh no, you can be a historian in different ways.” She went on to say that some people who study history become lawyers, politicians, teachers, and yes, “writers.” That perked my ears.

“What do I have to do to be a writer?” I interrupted. “Well,” Mom explained, “You have to write what someone wants to read.”

Knowing we had three different books about General Patton on one of our family bookshelves, I retrieved the thinnest copy and sat down at the dining room table to begin “writing.”

Later that day, when Dad came home, he asked me what I was doing. “I am writing a book!” I proudly announced.

“Oh really?” he asked as he glanced from my paper to the open Patton book next to it. “It appears you are copying this book,” he remarked, more a statement than a question. “Yes! That’s how I am going to write my first book!” I continued to beam.

“Copying someone else’s work, isn’t writing,” he explained. “You have to study the event, look for other people’s accounts about it, and then put them all together in a way that can help you tell that story to others.” That sounded like too much work. I stopped wanting to be a writer.

The Devil IS in the Details

For my entire life, I have been detailed-oriented. My toy soldiers had to be the correct scale for the toy vehicles they battled. When I was about 12, I threw out my Airfix Civil War scale figures because they all were attired with Mann’s accouterments—an uncommon item on actual Civil War battlefields.

In later life, this attention to detail transcended my collecting: I had to have examples of every variant I collected, whether helmets, tunics, buttons, or whatever. The drive for distinguishing the nuances of details drove me to collect—all under the self-aggrandizing notion of “preserving history.”

Don’t worry…I am not going to digress into the psychology of collecting and the role it plays in satisfying an empty space in our individual beings (though that is a topic I have studied, contemplated, and wrestled with for many years). Instead, this brief treatise was prompted by a note I received from a friend who recently returned from a Vietnam vacation. He wrote to me about his concern of the growing distance between the objects we collect and the history they represent:

“Since we have no way to document the military service history of a relic or vehicle, it is easy to put distance between real history and your favorite a favorite relic. One reason I don't own a military ambulance is because they represent pain and suffering –real human history."

His note continued, "To that point I want to tell you about the remains of a half-track that is on display in Vietnam. While not restored, it represents a vehicle that deserves thoughtful consideration. Regardless of point of view, the Vietnamese do a good job of documenting their military artifacts by using units and sometimes the soldiers names that used them. The former American WWII M3A1 half track on display in Hanoi, was provided as military support to the French Army fighting the French Colonial war in Vietnam from 1946 through 1954. The display placard confirms that this Halftrack was stopped, damaged and captured in ambush action by Viet Minh regiment 96 at the Dak Po bridge near An Khe in Gia Lai province. The Viet Minh over ran the French Column known as Groupement Mobile (GM) 100 in a sharp combat action on June 24th, 1954. That action is well documented and detailed in the book "Street Without Joy" by Bernard Fall. This is a vehicle with documented history. It stands with rusted guns pointing outward as a remembrance of the soldiers who fought and perished in that combat.”

My buddy had boarded a train of thought I have been riding a lot, lately. As I look at my collection displayed in my office, the relics represent individual histories of the soldiers who once wore the uniforms or carried the weapons. My collecting, over time, has evolved from detail-oriented, to “detail collecting.”

What’s Important?

Scattered through my office are little note cards to myself, “Silence is Essential for Thought;” “You are a Writer. So WRITE (at least a caption a day);” and “Islam is not our enemy.” All of these are sort of like Stuart Smalley’s daily affirmations (you have to be an old Saturday Night Live fan to get that reference).

The one, though, that is front-and-center on my computer (actually blocking the camera from viewing me while I work) says this:

“A good writer does not take what is interesting and make it sound important. Rather, he takes what is important and makes it interesting.”

That is a challenge for any writer, but even more so, for any collector of military relics and vehicles. It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking heat-stamps on helmets are important. It is just as easy to think that F-bolts have to be used on Ford-produced Jeeps. If you don’t believe that these are traps, simply log into any internet forum dedicated to collectors….dissecting the minutia of militaria is the lifeblood of our hobbies. Many will even succumb to riotous arguments over these details without ever acknowledging that some soldier sacrificed their way of life to wear that helmet or drive that jeep, not caring for one second what the heat-stamp was on the brim or what bolts held the vehicle together.

I was 7-years-old when Dad coached me, “You have to study the event, look for other people’s accounts about it, and then put them all together in a way that can help you tell that story to others.” That is too much for a note card to hang in my office, but it sure would be nice if I could hand it to the next collector who wants to discuss the intricate details of the next widget they discover.

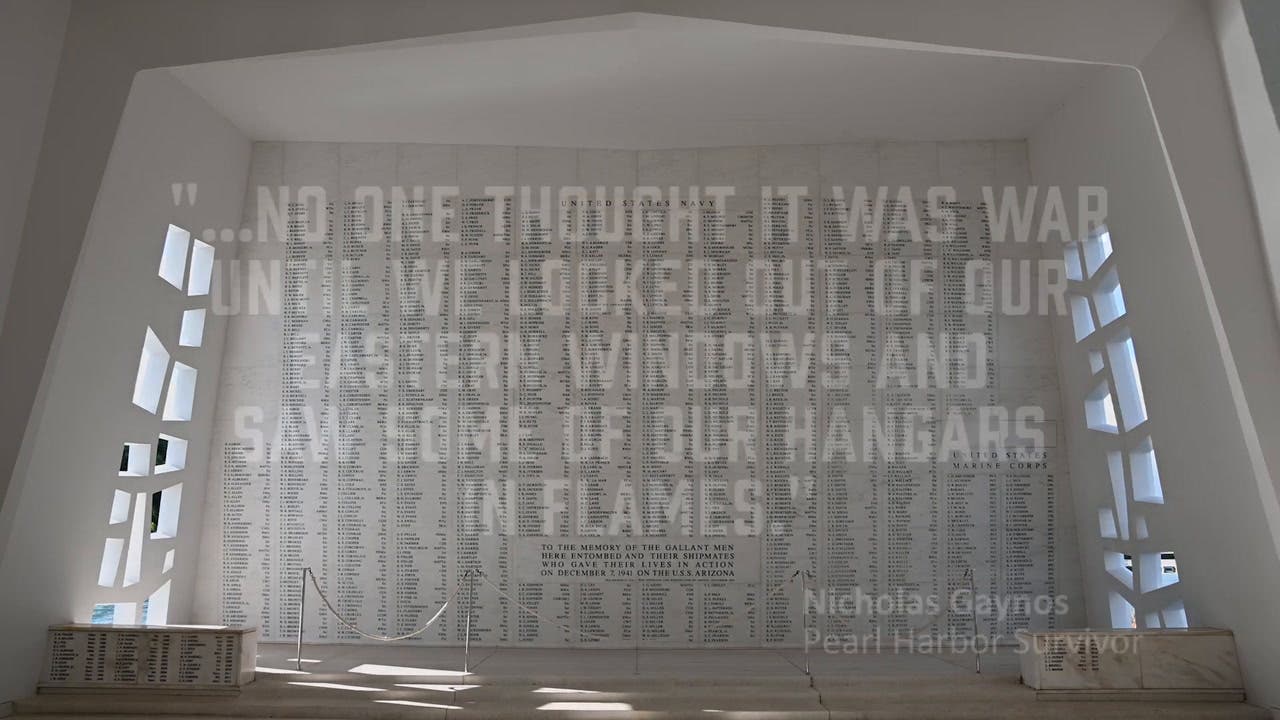

History is about the people, not the stuff. The stuff is what remains to assist us in telling the stories about those people. Let’s strive to keep the memories of the men and women who sacrificed in the forefront of our collecting.

Preserve the memories,

John Adams-Graf

Editor, Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine

John Adams-Graf ("JAG" to most) is the editor of Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine. He has been a military collector for his entire life. The son of a WWII veteran, his writings carry many lessons from the Greatest Generation. JAG has authored several books, including multiple editions of Warman's WWII Collectibles, Civil War Collectibles, and the Standard Catalog of Civil War Firearms. He is a passionate shooter, wood-splitter, kayaker, and WWI AEF Tank Corps collector.