Winches 101!

Extra pulling power can be an MV owner’s best friend

Winches on historic military vehicles usually come in two basic categories. The first is olive-drab eye-candy, meaning they are usually fully functional, but are rarely if ever used. The second category applies to folks who drive their vehicles in the off-road environments for which they were designed, and HMV owners who use their vehicle’s winches for work and/or in recovery situations. However, the operation and maintenance of winches is sometimes poorly understood and performed no matter which category they belong to.

For many HMV enthusiasts a winch is simply an accessory that adds visual interest to a vehicle -- and there’s nothing wrong with that -- but it’s also “correct” only in the sense that a vehicle might have been equipped with a winch during its military service, but probably wasn’t. There are few specific guidelines, but as a general rule for cargo trucks -- the vehicles which make up the majority of privately-owned HMVs -- WWII Dodge WCs, Chevrolet G-506s, GMC CCKWs, M-series trucks such as Dodge M-37s, Kaiser M-715s, and the various deuce-and-a-halfs of all eras -- only about one in 10 were factory-equipped with winches. In the case of WWII jeeps, and while a few winches, both capstan and drum types, were installed, wartime production was severely stretched, so equipping jeeps with winches on a large scale wasn’t considered essential.

On the other hand, some vehicles, such as the Ford GTB were often fitted with winches; and winches were a universal item on DUKWs. And of course specialized vehicles, such as wreckers, bomb-service trucks and recovery vehicles always had winches…sometimes two or three of them. Back to the other hand, winches were rarely factory-installed on ½ ton WWII Dodges, and almost never on vehicles such as carryalls, panel trucks, and ambulances. There were a few exceptions for special duties, but if you find an ambulance with a winch, it was almost always added by a former civilian owner.

One can take perfect pride in owning any HMV without a winch, but of course there’s nothing wrong with adding a winch, whether for show or actual use, but don’t feel obligated to just because “everybody else’s” vehicles seem to have one. In fact, a young person going to an HMV show today might get the impression that most cargo trucks originally came with winches. Still, if you use your HMV off-road it’s often better to have a winch and not need it than to need one and not have it. And if you have one, you may need or want to use it, so it should be kept well maintained. You should also understand the limitations of a winch… it is not a miracle device to always get you out of trouble, nor does having a winch transform your vehicle into an unstoppable terra terror. You should also be aware that there are few pieces of HMV equipment that can be as dangerous as a winch in the hands of an inexperienced or careless operator.

In this article we’ll cover winches in general for most common HMVs. Obviously we can’t go into detail about mounting on specific vehicles – buy a manual for your vehicle -- but most types of power take-off (PTO) winches operate about the same, and what applies to the mounting, maintenance and operation of one will more or less apply to all, including DUKWs; and in many cases also to the larger winches of wreckers and recovery vehicles.

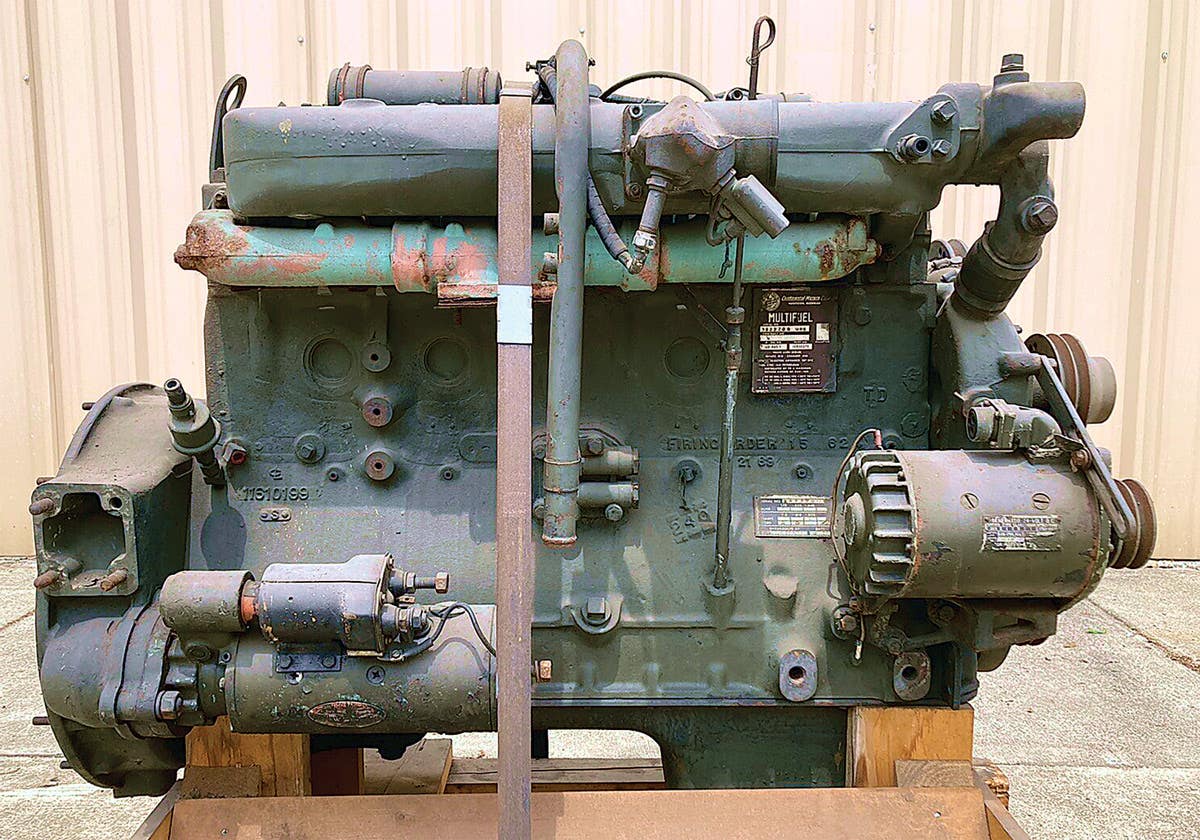

The illustrations show the basic components of typical military vehicle PTO winches. These will be about the same set-ups whether you have a WC, an M-37, or most of the common larger trucks. The three main parts of most PTO-operated winch systems are the winch itself, the winch drive shaft, which may be a single long shaft or two or three short ones -- a DUKW’s rear-mounted winch system is essentially the same except for the longer, multi-sectioned drive shaft -- and the power take-off unit. The PTO is usually mounted on the main transmission, though sometimes it’s on the transfer-case. It’s usually controlled by a single lever, which may be attached directly to the PTO unit or uses a remote linkage. Some small civilian winch PTOs are single-speed, meaning that when engaged, whether in forward or reverse, they turn the winch at only one speed (yes, you can increase that by speeding up the vehicle’s engine). On most common collector HMVs the PTO is a two-speed unit, high speed used primarily to spool out cable (or “wire rope,” though “cable” will be used in this article) while low speed is usually used for winding in cable under some sort of load.

If your vehicle’s data plates don’t include a winch diagram, it’s a pretty safe bet the winch was added later, and you will of course want to install the correct plates.

We’ll get to actual winch operation in a while, but note the floor latch on the winch control lever in the illustration: this prevents the lever from being accidentally engaged. If your vehicle doesn’t have such a latch, or if you’re installing a winch, make sure you get one.

It may look like a simple, steam-age device, but a winch requires proper maintenance and adjustment for safe efficient use and long life. It’s basically a worm gear driving a shaft, but the winch drum, which holds the cable, is not part of, nor is connected directly to, the driven shaft. Instead, the drum is free to rotate on the shaft like a spool of thread on a pencil, and is usually connected to the shaft by a sliding clutch, which is controlled by an external lever. By disengaging this clutch the winch drum can free-spool, such as when pulling cable out to be hooked to something. The military seems to have been of two minds at various times about whether this clutch should be left engaged or disengaged when the winch wasn’t in use. Leaving it disengaged is best from a safety standpoint; that way if the PTO lever is accidentally engaged while the vehicle’s engine is running the winch won’t start spooling out cable… or rip the vehicle’s bumper off if it starts winding in. The only reason to leave the clutch engaged is to keep tension on the chain, but if the brake is adjusted properly it should keep the tension sufficiently tight by itself.

Some winches also have a drag brake which, when properly adjusted, keeps the drum from over-running and back-lashing the cable like line on a fishing reel.

By nature a worm gear tends to hold its position even under load, meaning that the worm resists being turned by the gear instead of vice-versa; however, most winches are also equipped with an automatic brake. This may be a band type, or it might be a wet-pack clutch inside the gear case. There are variations of how they work; generally the band type automatically disengages when the winch is under power and clamps down again when power is removed. While band types may be external or internal, the clutch packs always run in the gear case oil, so it should be obvious that the correct oil and level must be maintained. The band types need to be adjusted from time to time; and the brake linings or clutch material wears and will eventually need to be replaced or relined.

We have now covered the three basic parts of a PTO winch system -- PTO, drive shaft or shafts, and the winch itself. Probably the best place to go from here is to imagine you have just purchased an HMV -- anything from a Dodge WC to a Reo M-35. The vehicle came equipped with a winch…let’s assume from the factory. We’ll get to winch maintenance and adjustments in a bit, but for the moment we’ll also assume the winch system is in good condition and ready to use… except we should always check the gear case oil level. Let’s familiarize ourselves with its workings now so that the adjustments and service procedures will make more sense later.

First, as stated above, check the gear case oil level. On most winches this is done by removing a pipe plug on the top of the case. As with the recommended position of the sliding clutch, the military seems to have changed its mind several times as to the correct oil level in winches -- anywhere from up to the filler neck to an inch below. Leaving some room for expansion in hot weather is a good idea, but the level should always be high enough to cover the worm and part of the driven gear. If the oil seal on the worm shaft leaks, it’s an easy job to replace, and seals should be available by number at most bearing and seal supply companies. For most vehicles the same 90 weight gear oil as used in the transmission, transfer-case and differentials will serve in the winch… though read your manual. Be careful about using “slippery” additives or STP as this may affect the operation of the drag brake or clutch-pack if internal. The PTO unit usually shares oil with the transmission or transfer-case, so it’s serviced whenever they are, but if the PTO is equipped with an oil level plug, it should be checked, though be aware that some PTOs simply came with such plugs, and since they are often mounted below the transmission or transfer case’s oil level, the plug was not meant to be removed. See your manual.

Lubing the drive shaft universal joints, and carrier bearings (if used), is obvious, and look for grease fittings on the winch itself. There’s usually one on the end of the drum shaft, and sometimes on the outside ends of the drum. A few drops of oil should be put on the sliding clutch mechanism, control lever pivot pin and detent from time to time to keep them free and operating smoothly. Likewise on the PTO lever or linkage, and the lever safety latch. The military once advised pouring used engine oil on the cable to keep it from rusting, then changed its mind after finding the oil rotted the cable’s fiber core.

A few words of caution: the operation of winches is always safest with two people -- one in the vehicle’s cab and the other at the winch. Of course there may be times when you have to operate your winch alone, and you should use extra caution when doing so. While which cable may often be rusty, greasy, and/or full of snags, use extra care if wearing gloves, because gloves can be caught in a sliding clutch or rotating drum, or snagged on the cable when it’s winding in. Long sleeves are also a potential hazard, and just rolling them up is no guarantee they won’t slide down at just the wrong moment. Always stay clear of the winch cable when it’s under any kind of load or strain; cable stretches under load like a spring, and if it or the hook or the chain should break it will come snapping back and could hurt you. And, for the same reason, never straddle or try to step over a cable when it’s under load.

The best way to learn about your winch is to rewind the cable on its drum. Winches usually fall into two categories in respect to their cables: those that were seldom used, so their neatly-spooled cables will look like long coil springs when unwound, and winches that were used a lot, so their cables are stretched and will resist being wound back on the drum in any semblance of neatness. These kinds of cables are often full of snags. This resistance to winding in neatly will usually also apply to new cable; and the procedure we’re going though now could also be followed if you are installing new cable.

Let’s get the cable unwound, and we’ll take into account you might be working alone. If you are, then be prepared for some fast moves, and leave the vehicle’s cab door open. If you are working alone, you might consider rigging a temporary ignition switch, such as a toggle with jumper wires so you can kill the engine from in front of the vehicle (or wherever the winch is located).

Anyway, with your vehicle warmed up and idling, first unhook the chain. There should always be a short length of chain on the front of your winch cable. About four to six feet is the average length; and it’s considered poor practice to have any of it wrapped on the winch drum. It’s also poor practice to keep the cable so tight that it can’t be unhooked from the bumper or shackle without first engaging the winch. If you’re doing this with two people, your trusted friend is in the cab at the controls, and your fingers are in his or her hands. If you have a friend who tends to daydream, I suggest finding another person for this job. If you’re working alone, and/or this is your first time operating your vehicle’s winch, disengage the sliding clutch -- it should have been already disengaged -- and try to pull out the cable by hand. This may or may not work, depending on the winch type, its condition, and/or if it has a drag brake on the drum. If the drum will free-spool, start pulling the cable out into the field, across the yard, or down the driveway until it’s fully unwound and stretched out. An alternate method is to hook the cable to another vehicle and slowly and carefully drive it away, pulling out the cable. Use caution as you get near the end of what’s left on the winch drum so there won’t be a sudden jerk. Another method is to hook the cable to something -- another vehicle is good because you can leave it in neutral so it will roll when you reach the end of the cable and there won’t be a jerk -- but anything that will drag or will do. Then put your vehicle in reverse and carefully back up, unspooling cable. If you have to power-out the cable, you should be aware that when you get all the cable off the drum it’s going to start reeling back in the other way if you don’t shut the winch down immediately. To power out, engage the sliding clutch on the winch -- with the PTO in neutral -- then get in the vehicle, step on the clutch, engage the PTO lever in Reverse or Out position, and gently let out the clutch to start unwinding the cable.

If you are trying your winch for the first time, be alert for the following things: One, that the data plate on the dashboard might not be correct for the vehicle, and instead of spooling the cable out, you’re actually winding it in (remember, you can’t see the winch from inside the cab). Two, some previous owner may have wound the cable backwards on the drum, which does the same thing. Three (and very important) if when letting out the clutch you hear nasty noises or the engine stalls, STOP AT ONCE and find out what’s wrong! DO NOT under any circumstances assume that something is just a little rusty and try to break it loose by applying more gas! The normal load on an engine to power-out a winch is very slight -- it should barely hesitate at idle when you let out the clutch -- and the only normal sound should be a low whine and sometimes a little vibration from the PTO and drive shaft. If the engine stalls or threatens to, push in the clutch immediately and shift the PTO back to neutral! It is possible that the winch is merely stuck from rust or disuse -- sometimes the drum shaft bushings are seized -- but often there are much more serious reasons why a winch won’t turn, and you can avoid a very big expense and/or destroying a perfectly good winch by finding out why it won’t turn instead of trying to force it to.

The best example I can give was on a GMC M-211 I bought from a contractor. Whether done by accident, or by someone with a grudge against the boss, a 3/8-inch nut had been dropped into the gear case through the oil filler hole and had jammed between the worm and shaft gears, which are usually bronze. The first time I tried to power-out, the engine stalled. The smart thing to do would have been to stop immediately and get underneath to check things out -- PTO jammed? Unlikely but possible. Carrier bearing frozen on drive shaft? Possible. Drum shaft bushing frozen? Possible. But eventually I would have (and should have) put a pipe wrench on the winch drive shaft and tried to turn it. Then I would have found that it turned in one direction but jammed when going the other way. Elementary. Something is caught in the worm. But, no, I had to give it gas and try again. CRASH! A completely shattered winch drive gear. Maybe the drive shaft shear pin could have saved the winch, but someone had replaced it with a grade-8 bolt.

Anyway, if there are no nasty noises or a stalled engine -- and you’re working alone -- you’ll have to jump down and pull out the cable as it unreels. And then make a fast reentry to disengage the PTO at the end.

All right, one way or another you’ve gotten your cable off the winch drum and all stretched out. If it’s in poor shape -- badly rusted and/or full of snags and frayed spots – you may want to replace it… at least if you plan on actually using your winch in the future. Cable (or wire rope) comes in various grades. At the low-end is “plow cable,” which is stiff and hard to manage. It’s generally used for things like bracing telephone poles, and if you could get it wound on your winch drum, it would look like a coil spring when unwound again. Fiber-core wire rope is best, and the more finely wrapped and flexible the better… but also the most expensive. Of course you will buy cable with a breaking strength that exceeds the capacity of your winch and its shear pin. Read your manual.

If installing new cable, it usually attaches to the drum with a clamp or a wedge, which should be simple to figure out. Be aware that on some winches it’s easy to wind the cable on backwards.

To wind in the cable neatly and tightly there must be tension on it, and someone (maybe yourself) will have to be standing in front of the vehicle guiding it in. This is the most dangerous part of a winching operation, and once again I urge you not to attempt it alone. If you do, consider rigging up a kill-switch so you can shut off the engine at the winch. Use low speed on the PTO as well as the lowest engine speed you can get. Ideally, the cable should be fully stretched out in a straight line and attached to an object of sufficient weight to pull or drag and keep it under tension. Sometimes a cinder block is all it takes, sometimes a large anvil or the equivalent is better if the cable is new or sprung into unwilling coils; but be aware that whatever object you attach to the cable is eventually going to come very close, sandwiching you between it and your vehicle. After you’ve done this procedure once or twice you should have a pretty good idea of how to operate your winch in situations where it’s actually needed.

We’ve already covered basic PTO winch system lubrication, but there’s one item that’s often overlooked, and this is the yoke collar on the winch shaft in conjunction with the shear pin. As to the shear pin itself, we’ve already noted one example of what can happen if it’s replaced with something that won’t break before either the winch or the cable does. Genuine shear pins for specific winches are often hard to find. In most cases a soft grade-2 bolt will do. The use of grade-5 bolts is risky — sometimes they will be just as effective as shear pins on larger winches, but there’s a wide variance in the actual strength of most commercial fasteners, and many grade-5 bolts are stronger than they need to be. Likewise, most clevis pins, a tempting substitute, are at least grade-5 in strength, and may prove stronger than your cable or winch. The best way is to experiment, using a winch line pull that approximates your winch’s capacity, which is always rated at the first wrap of cable around the drum – read your manual -- beginning with the softest pin you can find, then working up the hardness scale until you get something that seems to consistently shear at about the right strain. As far as lubrication, the yoke collar should always be free to slip or rotate on the shaft if the shear pin breaks, so coat the shaft lightly with grease, and squirt some oil on the pin once in a while. On older HMVs, especially those used around salt water, it’s common for the yoke to be rusted onto the shaft, making the shear pin useless. If that’s the case, you’ll have to take it off -- heat and/or a puller may be required -- and polish and lube the shaft so the yoke is again free to turn. An easy way to check if the yoke is rusted or frozen is to remove the shear pin, and with the winch and PTO in neutral, try to turn the shaft by hand or with a pipe wrench. The yoke should spin on the shaft without turning the winch.

While you’re underneath inspecting things, be aware that another important part of the winch drive shaft is often missing, or at least improperly adjusted, especially on vehicles where the winch has been added later. This is the safety collar. It serves two purposes: the first is it allows the drive shaft to be made short enough so it can be removed without demounting the winch or the PTO. Second, it prevents the shaft from sliding backward and falling off the winch if the shear pin breaks. Since some provision has to be made for vehicle frame-flex, the safety collar should be adjusted with about 1/2-inch of clearance. Read your manual.

Other adjustments required from time to time to keep a winch operating properly are the drag brake setting, if so-equipped, and the automatic brake adjustment. The drag brake should be kept just tight enough so the cable can be pulled out by hand without the drum over-running and back-lashing. The brake lining material does wear out, but a brake or friction-clutch shop should be able to re-line it for you. The automatic brake is relatively long-lived and trouble-free. It should only be adjusted if the winch fails to hold under load when power to it has been removed (such as stepping on the engine clutch and/or disengaging the PTO). The brake should be tightened by small degrees until it will hold the winch under load with power removed. Over-tightening this brake will put an unnecessary strain on the drive system and winch gears, and will also wear out the lining material.

So far we’ve been dealing with winches that were already on vehicles when they were acquired. What about folks who want to install a winch on their present HMV? Here is some basic advice. The first tip is, buy an appropriate manual and read it. The second is, if you’re looking for a military-issue winch for your G.I. jeep, you’re in for a lot of frustration and disappointment; and you may also fall victim to scams. Such winches are very rare. There is nothing wrong with installing a modern electric winch on your jeep if you need a winch; and this can usually be done in such a way that removal for show is easy. For most other common HMVs, winches are generally available and usually reasonably priced. Most will be used take-outs, and some will have been abused. Examine all prospects carefully to make sure they have all their parts. Put a pipe wrench on the shaft and make sure they turn. Take a look inside the gear case to check the condition of the drive gears.

Another reason you need a manual is to make sure you’re getting not only the right winch set-up for your particular vehicle, but also all the parts for a complete and correct installation. Be aware that for many vehicles special front bumpers and frame extensions are part of the package needed to install a winch. Your best bet is to buy everything you need from a reputable source as a complete package. If you try to buy your parts piecemeal, either from different sources or by scouring parts yards, you’ll probably end up not only paying more but also wasting a lot of time. The second best way to make sure you get everything is to take it off a vehicle yourself. This has the added advantage of letting you experience what’s involved in installing a winch.

There are some things about installing winches that one may not find in manuals: one of these is that most Canadian M-37 type vehicles used a different transmission than U.S. models and the U.S. PTO will not fit on them (or vice-versa). Also, PTOs sometimes require shims to operate properly. Shims are available at commercial truck and equipment suppliers, or may be made out of sheet metal at home like cutting a gasket. Don’t be surprised if neither the “new” bumper, the frame extensions, or even the winch itself seem to want to fit the mounting holes on your vehicle, because its frame has been strained and set after many years. Except for the very rare military-issued jeep units, most winches are heavy: save your back by using the right kind of hoist or jack when lifting, moving, or positioning them… especially since the winch will seldom fit on the first try. Have a stout alignment bar, and be prepared to re-drill or enlarge some holes. Weight is also a factor on aged front springs. You might want to pile everything onto the front bumper first to see if you’ll have to add new leaves or have your springs re-arched.

But, when all is said and done, and even if your winch is never used for anything but pulling helpless saplings out of the back yard, it probably is better to have one and not need it then to need one and not have it.