Spring Time for MVs

The basic design of vehicle leaf springs hasn’t changed much in over a century. Until around the 1950s, the general rule for truck springs was to make them massive. Keeping the “spring” in your vehicle’s springs may take a little elbow-grease.

One summer during my teenage years, I worked as a wood cutter in the coastal mountains of Central California. I had a silly notion that it might be a vacation from real hard work in my dad's scrap yard! Wood cutting was just one of many jobs that I would throw myself into with all the mindless enthusiasm of youth, often thinking they were so much fun it was hard to believe that some fool was paying me to do them. However, these days I realize they were hard, dirty, dangerous, and ridiculously underpaid jobs, and I'm really lucky to have survived some of them. The miles eventually catch up with people just as they do with vehicles. I can usually remember where and when I acquired most of today's "malfunctions." I recall very well almost breaking the arm that now aches whenever it rains: I was dismounting a 500 pound solid rubber tire from a Scoopmobile in Arizona. The tire came loose with unexpected ease and fell on me. I was working alone and spent an hour in the sand wiggling out from under that tire, while the dinner bell seemed to be sounding for every red ant south of Tucson. My Alaskan adventures probably account for my absolute horror of cold; and the thumb that doesn't work right came from battling a huge old dinosaur of a chain saw--a gear-drive "Mac"-- back in my wood cutting summer.

I took these jobs because I like being my own boss and prefer to work alone. Of course, I probably helped make a lot of people "rich" while ending up with little for myself except a few experiences which I hope might amuse, or at least not annoy, the readers of this magazine. The wood-cutting gig was typical. I was given a pack-rat-infested trailer, a battered old dinosaur of a saw, and was paid by the cord for all the oak and madrone I could truck into town. While there was plenty of fresh air, sunshine, and solitude plus the pride of an "honest day's work for an honest day's pay" (I can't say that with a straight face anymore) there were also plenty of deer flies, yellow jackets and ticks. However, the really cool element to this and many other such jobs was the TRUCK--a 1943 Autocar U7144T, cab over, six-wheel-drive... one of the most awesome vehicles I had ever seen up to that time.

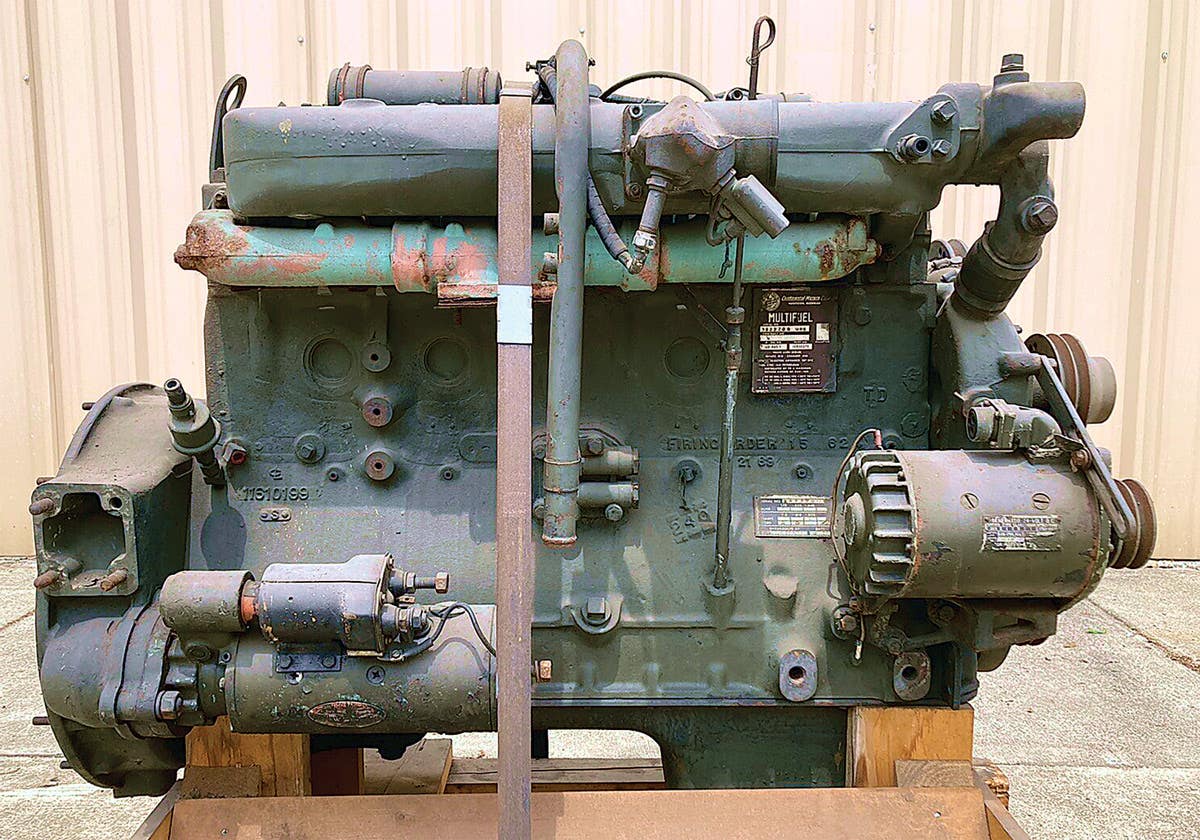

For MVM, readers not familiar with the heavy and lesser-known U.S. Military trucks of WWII, the U7144T, along with similar models manufactured by White, Kenworth and Marmon-Herrington, was built as a tractor in both open and closed cab versions. My wood truck was a closed cab model. It had a Hercules RXC 529 cubic-inch engine, a five-speed non-syncro transmission (5th gear O.D.), a two-speed transfer-case, and an early style air-brake system with a mechanical parking brake. This particular truck had been fitted with a stake bed, but was otherwise stock, right down to the blackout lights and tiny round mirrors. It was capable of about 45 mph on the highway; but the owner made me swear never to exceed 35...especially "going down the mountain." As with most heavy MVs of WWII, relatively few examples of U7144Ts survive today, though I have seen several fine restorations. These trucks were also a favorite vehicle for house-moving companies, where brute power at low speeds was needed.

The Autocar was just as at home in those mountain woods as the long-vanished grizzly bears. It could climb any trail, even the almost vertical firebreaks cut by Caterpillars. And what it couldn't climb over or crawl around, it could generally knock down or bull through. It usually took me about three full days to fell the trees my boss had marked, cut and split the rounds, load the truck, and drive it thirty miles into town, then unload and stack the cords in the wood yard. Looking back, I realize that I probably didn't have to work that hard--in fact, my boss seemed surprised that I did--but, after all, if I didn't cut and load the wood I couldn't drive the truck. I felt very mature to be trusted with the truck, and did my best to follow the boss's instructions about its care... though keeping the downhill speed below 35 mph on those steep mountain roads with a load of wet wood and those old-fashioned brakes was impossible.

The truck had no tachometer; but it was obvious that the huge old Hercules engine did not like high revs. I would come to a stop at the beginning of every long grade, make sure I had a full tank of air (sometimes the unloader valve stuck) then start my descent in the lowest gear, shifting up only when the engine began to rattle and roar, and trying to use a minimum of air for the brakes. Nevertheless, we would usually arrive at the bottom of grades in top gear at max RPMs with smoke pouring out of the brake drums. It's typical of youth that I don't recall ever being worried about my own skin; I was only concerned for the truck.

DON'T LET THE SPRINGS FLATTEN

My boss had several other rules about his vehicle. One was to never leave the cab doors open, "because they would sag." Another was to never let the truck sit loaded overnight, "because it would flatten the springs."

He was right on both counts; and even today I never leave my vehicle doors open. As for the springs, and while anyone who has ever seen the springs on an Autocar U7144T might wonder if any load less than a Liberty Ship could possibly flatten them, I have found that it's still good practice never to leave a truck sitting loaded any longer than necessary. This advice applies to MV owners who want to save space by storing a Jeep, MUTT or a ton of spare parts in the back of their deuce-and-a-half.

No matter how well arched and beefy a vehicle's springs may have been when they first left the factory, and no matter how light a load a truck may have carried in past lives, thirty, forty, or sixty years of just sitting idle or merely toting itself around have probably flattened and weakened its springs. In this article we're going to examine some ways to restore the arch (or arc) and strength to a vehicle's leaf springs, and/or to raise it back up to its original body height. We will also discuss coil springs, as used on MUTTs, many CUCVs, and the M998 HMMWV.

BASIC SPRING DESIGN

The basic design of vehicle leaf springs hasn't changed much in over a century. Until around the 1950s, the general rule for truck springs was to make them massive. In fact, I've driven a few old trucks with a spring-rate so stiff that it always surprised me that their cabs weren't shaken to pieces. For heavy, long-distance, over-the-road trucks, driver comfort was usually provided by shock-absorber, spring, or air-cushioned seats rather than softer suspension systems.

Typical installation of a coil helper spring. Although existing leaf springs aren't shown in this picture, one should get a good idea of what is involved in installing such springs. It is important to check tire and brake line clearance, as well as inspect the springs from time to time after installation because their mounting hardware often works loose.

On the other hand, for automobiles of the late 1940s up into the mid 1960s, "mushy" seemed to be the most sought-after quality in springs. This was probably because most U.S. highways were paved by that time, so cars didn't have to contend with dirt roads, chuckholes and ruts anymore. One may also wonder if a soft ride was Detroit's way of enticing the generation who had won WWII into buying new cars. Many of that generation had painful memories of hard wooden benches in the back of CCKWs. Some readers may remember the era when every new model was "longer, lower and wider" than the previous year's. This was the era when one sat on a seat like a living room sofa aboard a Cris-Craft plowing through quicksand and wallowed around every corner like a drunken hippopotamus.

Coil springs were used on many American cars, as well as the new Ford-designed MUTT and were also experimentally tried on light and medium-duty civilian trucks with varying degrees of success. For example, early 1960s Chevrolet pickups had a nervous and floaty coil spring and trailing-arm rear suspension.

Front torsion-bars were also tried on light and medium civilian trucks--many of the early to mid 1960s. GMC trucks had them. Ford introduced the "Twin I-beam" and coil front suspensions--the cause of what was known as the "Bronco bounce" among 4x4 fans in those days.

Many of today's truck manufacturers have gone back to leaf spring suspensions. For one thing, they're the simplest form of suspension system. For another they're also the cheapest. Most common collectable U.S. military trucks have leaf springs both front and rear.

LEAF SPRINGS

As a general rule, the more leaves there are in a spring assembly the better a vehicle's ride. Also, the more leaves, the more versatile the spring. This means that more leaves will usually give a better ride under all operating conditions. Of course, more leaves cost more, so it's not surprising that truck manufacturers--especially those of pickups--began to see how few they could get away with. As I mentioned in an article about Dodge M37s (MVM #104), the all-time worst ride I ever experienced in any vehicle (except a Linn half-track or Ford GTB) was a 1977 Chevy Silverado 3/4-ton 4x4 pickup. There were, if I recall, only two long stiff leaves in its front spring assembly. The truck's ride on a freeway could have been politely described as "choppy," while off-road the truck would try to put my head through the cab roof when crossing a desert wash or hitting a chuckhole. Come to think of it, even the half-track and Burma Jeep rode better than that Chevy because they didn't bounce! On the other hand, the M37 I had at the time rode like a vintage Cadillac by comparison. This was because an M37 had a lot of leaves of varying lengths in its spring assemblies.

It isn't hard to understand how a leaf spring assembly works. It's relatively easy to engineer your own spring-rates by "field-repair" methods, though the actual arch of the springs (how high a vehicle sits above its axles) usually requires professional help. Most cargo trailers have very short leaves because ride isn't a big concern. In the case of that bizarrely-sprung Silverado (which did have long leaves) the problem was that there weren't enough leaves. In other words, two heavy leaves, no matter how long, can't be as versatile as five or six lighter ones.

Cargo vehicles present the biggest challenge when it comes to spring design because a truck must be able to comfortably carry its rated load--so its springs must be stiff--yet it shouldn't ride like a brick on a skateboard when empty. For most smaller MVs such as Jeeps, Dodge WCs and M37s, a compromise was made...and for these vehicles it was usually made very well.

The exception to well-engineered springs on common U.S. MVs is the Kaiser M715. This was a civilian pickup (the Jeep Gladiator) adapted from a 3/4-ton design into a 1-1/4-ton military truck. This was accomplished mainly by giving it heavier springs. However, the leaves were so stiff that the truck often got stuck in twisted situations where the right front and left rear wheels (or vice-versa) lost contact with the ground. This is another example of how a compromise must be made, especially on a military vehicle: make the springs stiff to carry weight and they may be too stiff to flex enough on rough off-road terrain.

A well-designed leaf spring assembly usually has a lot of leaves. The long leaves give the best ride when empty, while the shorter leaves take more and more of the weight, making the assembly stiffer as the vehicle is loaded down. This is called a progressive spring assembly, meaning that it adjusts to its load. Most modern coil springs, such as those used on MUTTs, HMMVWs, and CUCVs are also progressive. This is usually accomplished by making the coils wider apart in the middle of the spring and closer together at one or both ends. In a no-load highway situation, most of the flex is in the middle of the coil, which gives a softer ride. When the vehicle is loaded, the middle compresses, making the whole coil shorter and stiffer.

Still, even the most well-designed springs are a compromise on cargo vehicles, because a single assembly can't provide the most desirable ride under all conditions and loads. Therefore, larger trucks usually have what are commonly called "overload springs" (these should properly be called "secondary springs"). This is because they are not for overloading beyond the vehicle's rated capacity, but instead are intended to take over part of the load by making contact with their pads as the vehicle is weighed down. This allows the main spring assembly to be built lighter and with more flex to give the vehicle a better ride when empty, and is the same concept as making a coil spring wider in the middle.

Tandem-axle-drive trucks such as deuce-and-a-halfs, can have heavier and stiffer rear spring assemblies due to the fact that twin axles provide a lot of flex by being able to move independently. And, there isn't much one can or should do to try beef up or modify these. It's a rare deuce that has been used so heavily that its rear springs are worn out, with the exception of tippers, tankers, and sometimes shop trucks. If the springs on such vehicles are worn out, then replacing them is usually the simplest, cheapest, and best option.

LEAF SPRING REPAIR

Since Jeeps, WCs, M37s, and deuce-and-a-halfs with leaf springs are the most common U.S. hobbyist MVs, let's talk about repairing, replacing, or beefing up their springs. Even M715 owners might benefit from some of this advice, though there isn't really a simple quick-fix for your five-quarter's starchy suspension. To vastly improve an M715's ride, one would probably have to replace all the springs with custom-designed assemblies. But, if it makes you feel any better, the stock springs usually don't sag very much.

As an aside, most of those fabled Jeeps in boxes (TUP Packs) suffered from flattened springs because they were banded down tight to save space. But, again, the springs of all vehicles, no matter how well treated, will eventually weaken and sag with time. This is a form of metal-fatigue. It's the same reason why gun owners hate to keep a clip loaded; or why fishing rods or boat oars should never be hung horizontally. There are many factors in how badly or quickly leaf springs will weaken. Naturally a lot depends upon how and where the vehicle is used. However, how strong they were to begin with is another important factor. This has a lot to do with the quality of steel from which they were made.

"Simple" is a relative term when it comes to vehicle modifications or repairs: we speak of "dropping in engines" or "pulling transmissions" either from experience--or lack of same--which often confuses the middle-ground mechanic or the do-it-yourself MV owner when he or she finds that "dropping in an engine" is really not that simple. So, too, we often hear casual references about "re-arching" (or "arcing") leaf springs as the best and simplest way to solve a sagging problem, though we may not fully understand what's actually involved. Re-arching is probably the best way to restore a vehicle's height and ride, but for many people the thought of removing all four spring assemblies--which means jacking, blocking, and removing the axles, as well as (usually) fighting rusted nuts and bolts--seems anything but simple (this is also what one would have to go through if replacing a vehicle's sagging springs with NOS or new assemblies).

Once the springs are out of the vehicle, take them to a shop where skilled and experienced people heat and bend them back into their original arch and strength. If done correctly, these rebuilt assembles are often better than NOS, beca use, unlike mass-produced factory springs, they are given careful attention. But neither fix is cheap, though for some MVs, NOS springs may cost a lot less than having the old ones rebuilt.

As most veterans know, there are usually three ways of doing things: the right way, the wrong way, and the Army way. There is also a fourth way..."the field-repair way." In the case of vehicle springs, the field-repair way probably isn't as good as having them rebuilt or installing NOS or new assemblies, but it's definitely cheaper. However, it still involves all the work, and more, of the other three ways.

This is a typical coil helper spring kit of the type that may be found in most auto-mart stores, mail-order, and online catalogs. Such kits usually come in 1000, 1500, and 2000 pound capacities. However, the manufacturer's estimates are usually optimistic. For this reason, it would be wise to use the "1500 pound" springs even on small MVs such as Jeeps.

If one doesn't use their MV for actual work, much off-roading or cargo-carrying, then about the only reasons to fix its flattened springs would be for the sake of appearance...to restore the original stance and height (tail a bit higher for M37s) and/or to bring back its factory ride. If one is restoring an MV for show, then it's usually better to have the old springs rebuilt or replace them with new or NOS assemblies rather than do any field-repairs.

On the other hand, if one only wants a macho-looking vehicle that sits up high on its axles, one might not care about how they lift it, or how it rides afterward. The bargain-basement way of raising a vehicle's body is with longer spring shackles...like a lot of kids used to do with their first suicide-machines. This is the wrong way for many reasons, some of which were discussed in past articles dealing with front-end shimmy and axle alignment. I did it once when I was a kid on a '64 International Scout; and though I don't know for sure if that was the reason, the Scout broke two spring leaves shortly afterward.

Another cheap way to raise a vehicle is by installing lifting block kits, which are usually available at auto-mart stores and "fo-buh-fo" accessory shops. While this method is at least mechanically better than using long shackles, it can also mess up the front-end alignment. This can result in annoying or dangerous handling characteristics. Improper use of lifting blocks can also misalign a rear axle, putting the U-joints out of sync and causing their premature failure. Neither longer shackles nor lifting block kits can strengthen or restore a sagging spring system. All they do is raise the body a little higher above the problem.

Yet another quick-fix was suggested some time ago in letter from one of our readers. This was installing coil helper springs, which bolt onto a vehicle's axles between the axle and frame. Like longer shackles and lifting blocks, these helper spring kits can usually be found at auto-mart stores, as well as from sources like J.C. Whitney. If chosen with care as to weight-capacity, and properly installed, such kits can make a big difference in vehicle height. They will strengthen--though can't repair--a weak or sagging spring system. One company, Superior, makes these kits in 1,000, 1,500- and 2,000-pound capacities (though their estimates seem a bit optimistic). I have a set of these (Superior, Model #12-1500) on the rear axle of my 1965 Nissan Patrol, even though I "field-repaired" the flattened leaf springs. The coil kit now only functions when toting a lot of weight.

Such kits can usually be installed in about an hour on Jeeps, WCs and M37s, but pay careful attention to brake lines and tire clearance. Also be sure to check their mounting clamps for tightness now and again, because they tend to work loose. Even for a Jeep, I'd suggest using the 1,500-pound kit. Since these helper springs are generally out of casual sight when installed, they don't detract much from a vehicle's stock appearance.

The downside of using these kits is that if the coil springs are strong enough to raise body height, then they are basically replacing a vehicle's individually-designed leaf spring suspension with one-size-fits-all coils. The vehicle's ride will often be nervous and bouncy though new shock-absorbers may help.

One may see "Add-A-Leaf kits" when browsing an auto-mart store, mail-order or on-line catalog. I have tried them and I don't like them. These kits seem marginal at actually raising a flattened spring system, though they can prevent it from sagging more. Many such kits require unbolting the axle from the springs to install; and if one is going to go to all that trouble, then why not fix the problem by installing NOS springs or having the old ones rebuilt? Most of these kits are visible when installed and may detract from the appearance of a vintage MV. This seems to leave one with four good choices (forget the two bad ones) of how to raise a vehicle and strengthen its suspension system:

1. Replace the old springs with new or NOS assemblies. (applies to leaf springs as well as coils)

2. Have the old springs rebuilt (also applies to leaf springs and coils).

3. Install coil helper-springs on leaf-spring suspensions.

4. Field repair a leaf spring suspension.

As mentioned earlier, the field repair way may not seem simple to some home mechanics. It involves the same jacking, blocking, axle-dropping, and fighting rusted bolts and fittings as replacing old springs with new ones or having the old springs rebuilt. In fact, it involves more work and time then doing the first two fixes and much more than doing the third. It does, however, have two advantages: it's a lot cheaper than doing the first two and does a much better job than the third.

Nevertheless, it's usually not a good option for really restoring a vehicle...and while you may not care about restoring your MV at the moment, you may want to restore it someday. If so, you would have to replace your springs all over again.

REMOVING SPRINGS

As I've mentioned in previous pieces, my current "MV" is a 1965 Nissan Patrol, though there is very little about it that's Nissan anymore, except the body, frame, and axles. I replaced the original in-line six-cylinder engine with a 304 IHC V-8. This is a dedicated truck engine and very heavy for its cid size. It was far too much weight for the already weak and sagging front springs, but for reasons involving time and money I wasn't able to fix the problem correctly, or even do a good field-repair. Instead I made do with coil helper springs for several years. At last, I briefly found myself with some extra time and a bit of money. I went to a spring shop to check out the cost of having the Nissan assemblies rebuilt and adding extra leaves. However, I wasn't about to pay $250 per spring assembly!

A typical front leaf spring assembly as used on WW II Dodge WCs and Dodge M37s. Note the four rebound, or leaf clips. Also note how the spring assembly is attached to the vehicle's frame and axle. This should give one a good idea of what would be involved in removing and replacing a leaf spring assembly.

I promptly drove to a truck wrecking yard, and after taking measurements of the Patrol's spring leaves, searched among the rusting corpses until I found a stout set of rear springs on a 1970s Ford 1-1/2 ton truck with leaves of about the same length and width as the Nissan's, but heavier. These springs still had a nice arch even with two other trucks stacked on the Ford's frame. Since I wasn't going to use the Ford's top leaves--the Patrol's top leaves were kept to attach to the spring hangers and shackles --it was a simple matter to have the Ford assemblies torched off. So, within half an hour (and for only $80) I had enough sturdy and well-arched leaves to rebuild my Patrol's entire system, front and rear.

I'm assuming that if one feels up to this job, one also knows what's involved in removing and remounting a vehicle's springs. Besides the obvious--jacks, and adequate blocks or stands, one needs a good basic tool set. About the only special tools needed are a pair of heavy C-clamps. If you plan to add more leaves to your vehicle's assemblies, you should measure to see if your present axle U-bolts are long enough to compensate for the extra thickness. The nuts should always be fully threaded onto the bolts. If not, you will have to get new U-bolts, which are available at most auto parts and 4x4 stores.

It should go without saying that you'll have to jack up and block your vehicle by its frame, unbolt the axles from the springs--taking care with steering linkages, shock-absorbers, and brake lines. Then, unbolt the spring assemblies from their hangers and shackles. On most common MVs, the leaves are held together as a unit by a single center bolt, and there are usually two (sometimes four) rebound clips. The purpose of the clips is to keep the leaves aligned fore and aft, and to prevent the spring assemblies from opening up like an accordion then slapping back together when the vehicle bounces. Some of these rebound clips use a bolt, while others are bent into place. They are usually also riveted to a spring leaf to keep them in position.

How one goes about dealing with them will depend upon your own vehicle and whether or not you're adding extra leaves. You can usually unbend to remove, reshape, and then re-bend the clips at least once without breaking them cold, but having a torch to heat them makes for better blacksmithing. The rivets can be removed with a hammer, chisel and/or grinder. Rivets are still available at many hardware stores. Grade-2 bolts can make satisfactory substitutes for rivets; and with a little imagination and drilling you can reinstall the clips on your "new" spring assemblies just as if they came from the factory that way.

Although the center bolt often has a cylindrical head for locating the axle pad onto the springs, it is otherwise usually just a 5/16" or 3/8" SAE-thread Grade -8 bolt. Many times you'll find its nut is hopelessly rusted on, and the bolt will break when you try to remove it. It's probably a good idea to replace the bolt anyway. If you're adding extra leaves, then of course the replacement bolts will have to be longer than the originals. You can buy these special bolts at most spring shops, but a little grinder or file work will adapt the heads of ordinary Grade-8 bolts to fit the locating holes in the axle pads. Use Grade-8 nuts along with them.

M211 rear springs. Typical of many deuce-and-a-half and other tandem axle drive MVs. Note the secondary spring assembly that normally functions only when the vehicle is loaded. This allows the main spring assembly to be built lighter, providing a smoother ride when the truck is empty. Note the rebound clips (also called leaf clips) on both spring assemblies.

Use caution when removing these bolts from the spring assemblies, as the leaves may fly apart when the nut is removed, or if the bolt should break. Also be careful if you get the nut off but the bolt is rusted in place, because it may let go suddenly and scatter spring leaves all over you.

Building your new spring assemblies is just a matter of stacking leaves. Your old top leaf is probably flat and won't willingly conform to the arch of the new lower leaves. It will when the springs are re installed and vehicle's weight comes onto it; but for now you'll probably need two C-clamps to draw all the leaves together while installing the center bolt. Keep in mind that the spring leaves want to fly apart and can hurt you if they do. Use a little grease or anti-seize compound on the bolt.

When building your assemblies, remember that the more leaves you add, the stiffer your vehicle's ride will be. More long leaves (well-arched of course) will also raise your vehicle: but one or two strong and well-arched leaves will make a big difference in both stiffness of ride and increased body height. Don't build a suspension system that takes out your teeth when hitting a bump. Also remember that if you're raising the original factory height of your vehicle over about three inches you'll probably need longer shock absorbers, and maybe new flexible brake lines.

Once the springs are reassembled, the installation process is just the reverse of removal. Use plenty of grease on the shackles and hangers, and lube them again with a grease gun after everything is back together. Tighten the axle U-bolts securely. Now is a good time to replace worn bushings or install new shock absorbers. Be sure to recheck the tightness of the U-bolts, spring shackles, hangers, shock absorbers and rebound clips after a few miles of driving and at frequent intervals afterward until all the parts settle into place.

You will probably be very surprised and pleased by your vehicle's new higher stance. Whether or not you're happy with its new ride remains to be felt... hopefully you haven't turned your M37 into an M715!