MV BALL-KNUCKLE SERVICE

Inspections of a vehicle’s steering knuckle is particularly important for vintage MVs.

Except for size, most common military vehicle

axles that use ball-knuckle steering joints are

basically the same in the arrangement of their

parts whether on a jeep or a ten-ton G-792.

Specifics are covered in manuals, and if you

don’t have a manual for your vehicle, buy one.

Disassembly of a ball-knuckle joint requires

removal of the steering drag link on the driver’s

side, as well as removal of the tie rod, shown here

on both banjo and split axles of CCKWs.

By Steve Turchet

After several decades of dealing with auto, truck, heavy-equipment, marine, and military vehicle parts suppliers I’ve come to the conclusion that when employees and counterpeople are consistently rude to customers it’s because the company allows it. And, since the company allows it, the company must be rich enough that it doesn’t need either my or my own company’s money. I don’t expect anyone to kiss my behind, but I do hope for reasonably polite service when I throw down dollars.

Some years ago, I worked as a mechanic and equipment operator for a construction company. My truck at the time was a 1963 Toyota Landcruiser pickup, which carried my tools when I repaired and maintained the company vehicles and its many cranes and forklifts. I put a lot of miles on that truck and I thought I was keeping it in top condition, including doing frequent lube jobs and oil changes, as well as checking it over at regular intervals so I could fix things before they broke. However, one afternoon I was sitting in the company office and glanced out the window at my truck. One of the front wheels didn’t look right; it seemed to be leaning inward at the top instead of outward as most solid front axle 4x4s should. (This, by the way, is called camber.) I went out and shook the wheel but couldn’t find any apparent looseness in the wheel bearings or steering knuckle. But, when I jacked the front end off the ground I discovered the steering knuckle flopped all over! After pulling the knuckle apart I found the upper pivot bearing had totally disintegrated. My boss told me of a local Toyota dealer that wanted to sell him three new pickups, so I drove over there. The parts people were rude in the extreme, obviously thinking here’s a grimy guy in oily coveralls who wants one little bearing for an antique Landcruiser, and who cares. They had the bearing, but I wasn’t about to eat bull droppings to get it, and walked out. I found the bearing at a bearing house—for half the price—and that particular Toyota dealer didn’t sell three new trucks to my boss.

Removal of the ball joint oil seal: Components

vary with the type of axle but most disassemble

like this. On many vehicles the seal itself can be

replaced without taking the ball joint apart.

Keep the balls clean on the outside. If they’re

rough or rusty, use fine sandpaper or emery cloth

to polish them, and wipe them occasionally with

an oily rag. Clean off dirt or mud if you take the

vehicle off-road. Doing these simple things will

greatly prolong the life of the seals.

Aside from being a good example of how rude employees can cost a company money, it’s also a good illustration of why one should perform regular inspections of their vehicle’s steering knuckles. Just doing lube jobs is not enough. These inspections are twice as important if one owns a vintage MV such as a jeep with ball-knuckle steering joints and the vehicle is fitted with locking hubs. On many ball-knuckle vehicles the steering pivot bearings, the upper bearings in particular, were meant to be lubricated by the splash of oil from the rotating universal joint. If the vehicle has locking hubs and is used mostly on the highway with the hubs disengaged, the upper bearing doesn’t get oiled. If this is the case with your MV, you should lock the hubs and drive a few miles every week or every month depending upon how often you use the vehicle.

While looseness or wear in a vehicle’s steering knuckle can often be found while performing a lube job—assuming one is paying attention—a more thorough inspection can be performed by jacking the vehicle’s front end off the ground by its bumper or frame so the axle and wheels hang from their springs.

This, by the way, is also the best method of lubing the spring shackle bushings. Why? Because if you lube them with the vehicle on the ground the grease can’t get into the upper part of the bushings because the vehicle’s weight is resting on them. This also applies to the rear spring bushings.

Removal of the steering arm on the driver’s side

of the vehicle: On many such axles the steering

arm is part of the upper pivot bearing cover.

Shims are often used to set the pivot bearing

load, which one should check upon reassembly

and following the vehicle manual’s instructions.

The outboard portion of the knuckle should pivot

smoothly all the way, both left and right, when

turned by hand, and there should be no looseness

in the bearings.

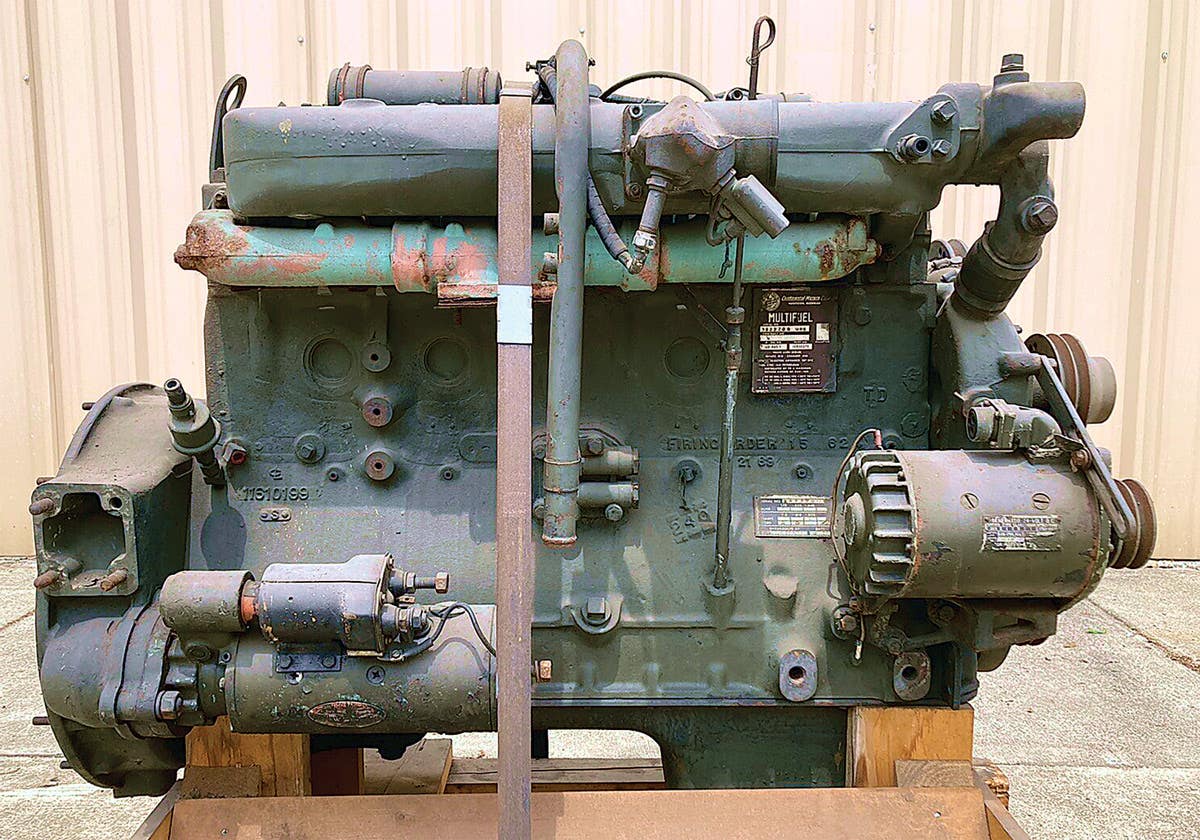

Anyhow, one should take all the proper safety precautions when jacking a vehicle’s front end off the ground, such as blocking the rear wheels and using adequate jacks and supports. Don’t use cinder blocks or bricks because they can suddenly crumble. Also remember that jack stands bought for a jeep probably aren’t adequate for a deuce-and-a-half. Speaking of deuces, be careful when jacking up MVs with sprag-type transfer cases, such as early model Reo M35s, because a wheel might spin as it leaves the ground. We don’t have the space to show the steering knuckle components of every common hobbyist MV, but the CCKW illustrations should give one a good idea of what most ball-knuckle steering joints are all about. Except for size, most of these axles are basically the same in the arrangement of their parts whether on a jeep or a ten-ton G-792. Specifics are covered in manuals, and if you don’t have a manual for your vehicle, buy one.

Once the front tires are clear of the ground point them straight ahead, then grab a wheel by the top of the tire and try to wobble it up and down. If the wheel bearings are loose, the wheel will wobble on its spindle. However, if the steering knuckle bearings are loose, BOTH the wheel assembly and the outboard portion of the knuckle will wobble.

On many jeeps the pivot bearings are bronze bushings, while larger MVs usually have tapered roller bearings. Many MVs have shims to adjust the clearance of these bearings... and here’s where having a manual is important. There should be no looseness in the ball-knuckle bearings... none at all. Even if they seemed tight in the wobble test, get a helper to turn the steering wheel. Watch each knuckle while the steering is run through a full cycle from one side to other and brought firmly against the stops, both ways. Watch what happens when the knuckles reach the end of their travel: the outboard portion of the knuckle should not appear to rise or lift, even slightly, when it bottoms out against its stop. Sometimes, even if the bearings seemed tight in the wheel wobble test, one may find looseness in this second test. If one does discover looseness, the ball-knuckle should be disassembled to find the cause.

Here are a few more notes about ball-knuckles. Most MVers know that ball-knuckle joints usually leak oil. However, instead of fixing them with new seals, some folks shoot the balls full of grease. Bad move. Grease doesn’t splash around so it can’t lubricate the upper bearing, nor will it run down into the lower bearing. The same concept applies to filling the balls with heavy oil, such as 140 weight, or a product such as STP. These are too thick to splash on the upper bearing or penetrate into the lower. And, neither “fix” actually fixes anything. Ball-knuckle steering joints designed to use oil are no different from transmissions, transfer cases, axle differentials or winch gear boxes; the manufacturers knew they would leak a bit around the seals, that’s why they provided plugs to check the oil level and top it off. And, just like the other above-mentioned components, the oil in ball-knuckles should be changed when it looks dirty, becomes contaminated with water or metal particles, or simply goes bad from old age. Even if one doesn’t drive their vehicle a lot, all the gear oil should be changed about every five years.

After removing the hub and brake drum, then the

brake back plate assembly, remove the wheel

spindle. Then the axle shaft can be pulled from

the housing. Take care not to damage polished

surfaces. While overhaul gasket sets are available

for the steering joints of most common MVs, one

can usually make their own gaskets more cheaply

from gasket paper. Many seals can be found by

number at bearing supply houses, with the

exception of the ball joint seal.

Most ball-knuckle joints use the same 90 weight oil as the vehicle’s transmission, transfer case and differentials; and just like those other components they will benefit greatly from top quality oil and/or a good oil additive.

If a ball-knuckle is leaking excessively replace the seals. That’s the only real fix. Keep the balls clean on the outside: if they’re rough or rusty, use fine sandpaper or emery cloth to polish them, and wipe them occasionally with an oily rag. Clean off dirt or mud if you take the vehicle off-road. If you have driven through deep water, check the oil for contamination and replace it if necessary. Of course, if your vehicle’s ball-knuckles are provided with lube fittings you should lube them at frequent intervals. Doing these simple things will greatly prolong the life of the seals as well as the life of the pivot bearings.

If you have to replace the bearings, replace the races as well. Generally, it’s the upper bearing that gets the most wear, but one should always replace both upper and lower bearings at the same time, and on both ends of the axle. You may find that on some smaller MVs that use bronze bushings, you can visit a bearing house and get roller bearings and races instead of bushings. Pack the bearings with wheel bearing grease before installing.

To begin disassembly, remove the wheel and hub from the axle spindle. This will be easier if you first remove the tire and road wheel, though on smaller vehicles such as jeeps it’s not totally necessary. Some large MVs have drain plugs on the bottom of the knuckle balls, but most vehicles most don’t so have a pan to catch the oil when the knuckle comes apart.

Remove the drive-flange nuts or bolts. On early jeeps with nuts on the axle end, remove the dust cap, the cotter pin—if the vehicle has one—and the axle nut. Then remove the drive flange.

If the vehicle is equipped with locking hubs, follow the manufacturer’s instructions for removing them. Some vehicles have cone-like inserts around the drive flange studs, and these can usually be loosened with a rap from a small hammer on the flange. Don’t lose these: replacements are often hard to find. You may need to use the flange’s puller screws to take the flange off. It’s a good idea to line up all the parts as you remove them, in a row on your work bench or floor in the order they came off and the direction in which they were facing, and to keep them in that order as you wash or clean them. This makes reassembly much easier. Some vehicles have an oil seal behind the drive flange, but usually there is only a paper gasket that generally gets destroyed when you remove it. You can make a new one from gasket paper.

Removing the drive flange should reveal the axle spindle and wheel bearing lock nuts. Usually there are two nuts with a retainer. These hold the wheel hub on the spindle. On most vehicles these nuts look like nuts, having six sides, though some GM vehicles have threaded rings instead of nuts, while other vehicles may have eight-sided nuts. However, as long as there are two somethings that function as nuts, there will usually be a retainer between them to lock them in place. Generally this is a tab-type retainer with one tab bent over the inner (adjusting) nut and another tab bent over the outer (locking) nut. Sometimes this retainer is a simple metal disk with an edge bent over the outer nut while on other vehicles it may be a spidery-looking thing. Using a small chisel or a screwdriver, straighten the tabs on the disk so you can remove the outer nut. Be gentle with the retainer because on older vehicles it has usually been bent, straightened, and bent again many times.

Removal of the spindle nuts is best

accomplished with a spindle nut wrench.

However, you probably don’t have such a wrench

(and it’s just as likely that whoever was in there

before you didn’t have one either and used a

hammer and chisel). If this is the case, be sure

your chisel is sharp, your hammer is small, and

try to do as little damage as possible to the nuts.

Removal of the spindle nuts is best accomplished with a spindle nut wrench, especially if the nut is not a conventional type. However, you probably don’t have such a wrench. and it’s just as likely that whoever was in there before you didn’t have one either and used a hammer and chisel.

If this is the case, be sure your chisel is sharp, your hammer is small, and try to do as little damage as possible to the nuts.

Usually it will only take a few light taps with the hammer to get the nut loose, after which you can unscrew it with your fingers. Beware of sharp edges left by a chisel.

When the outer nut is off, remove the retainer. Sometimes you will need to walk it off using two small screwdrivers as levers.

Then remove the inner nut. Some of these nuts have a raised shoulder or boss on the inner side which fits against the outer wheel bearing, and/or a dowel on their outer side which engages a hole on a ring-type retainer.

A typical ball joint axle stripped down. Note the

bearing races installed top and bottom. Many ball

seals can be installed from the inboard side

without complete disassembly of the joint. Some

people cheat and spit one piece seals so they won’t

have to go to this extreme just to install a little

piece of rubber or felt. While not recommended,

such cheating usually works provided the split is

installed at the top of the ball.

Keep these specifics in mind for correct reassembly. Sometimes there is a spacer between the inner nut and the outer wheel bearing. Remove this, if present, and note how it was installed.

Now, by gently rocking and pulling on the wheel, the outer wheel bearing should come loose and can be pulled off the spindle. Sometimes it will pop off by itself and land in the dirt, but no matter, you will be cleaning it later anyhow... though having it bounce across a concrete floor is not a good thing.

Then, with some additional rocking and pulling on the wheel, you should be able to remove the hub and brake drum assembly from the spindle. Use care not to drag the inner wheel bearing and oil seal over the spindle threads, possibly messing up the threads or cutting the oil seal.

Now you should be ready to disassemble the steering knuckle according to the illustrations, and the procedure is basically the same whether you’re working on a jeep or a G-792.

Reassembly is merely the reverse of disassembly. Once the knuckle is back together, check that it pivots smoothly all the way, both left and right, and there is no looseness in the bearings.

I’m assuming that if you were up to the job of replacing your ball-knuckle bearings, you would also know how to clean and repack your wheel bearings. Here is the procedure for reinstalling the wheel hub:

Slip the hub back over the spindle. Some rocking and waddling may be necessary to get the inner bearing to slip up onto the spindle’s inboard shoulder. Don’t drag the oil seal across the spindle threads.

Slip the outer wheel bearing in place, followed by the spacer (if used) and then the adjusting nut. If no spacer is used but the nut has a boss on its inner side, make sure you put it on the right way.

Tighten the adjusting nut. How tight is tight? Rotate the wheel by hand while tightening the nut and make sure the brake shoes aren’t dragging on the drum. As the nut is tightened, you will notice an increase in turning resistance as the bearings are seated in their races.

When the bearings are properly seated and tight, the wheel should rotate smoothly and freely with no wobble or slack on the spindle up to the point where further tightening causes the wheel to slow down and noticeably increases turning resistance. Recap: the wheel should rotate freely but not wobble on the spindle. (New or freshly repacked wheel bearings will usually loosen slightly after a few miles of driving and may need to be adjusted again.)

The retainer was really designed to be used only once and then replaced, but it has probably been off and on more times than you’d imagine. If it’s a tab-type, make sure that the tabs aren’t so fatigued they they’re likely to break off; and make sure the one internal tab that indexes into a slot on the spindle is still sturdy and whole.

If you have any doubts about the retainer, it would be safest to replace it. Slip the retainer into place, followed by the locking nut, and draw the nut up tight.

Bend one of retainer’s tabs across a flat of the inner nut and another tab over a flat of the outer nut. Now for the drive flange. If there was a paper gasket, make a new one from gasket paper.

Use gasket sealer on both sides. Install the drive flange—don’t forget cone inserts, if used—and tighten the flange evenly and securely. If your vehicle has locking hubs instead of a drive flange, follow the directions for installing them...and I assume you cleaned and serviced them as well? On early jeeps, install the axle nut, cotter pin (if used) and the dust cap.

Congratulations! You have just completed a vital bit of repair on your military vehicle; and by performing regular lube jobs, as well as inspections, you may not have to deal with rude parts people for a long time!