Ottoman Steel: Turkish helmets from the first World War

There remains no shortage of confusion over the Turkish steel helmets used in the First World War, and much of it is due to a few eager helmet collectors decades.

There remains no shortage of confusion over the Turkish steel helmets used in the First World War, and much of it is due to a few eager helmet collectors decades ago, and some obvious misunderstandings. One of the first dubious claims is that the helmet known as the Model 1918 was the first “Turkish steel helmet,” but that obviously isn’t correct.

All too often modern helmet collectors seem to believe that helmets became “a thing” during the First World War and overlook that soldiers donned the protective headgear for millennia. The origins of the Turkish helmet predate even the Ottoman era by a few centuries. In fact, it is worth noting that based on some written sources from the early Middle Ages, the name of the “Turkish” people comes from “tulga” — which happened to be their word for helmet!

The Turks took on the name as they were noted for their blacksmithing skills and due to the fact the early helmets were seen to resemble the Golden Mountains of Altai of Central Asia from where they may have originated before beginning their trek westward and eventually to what is modern-day Türkiye (Turkey). How much of this is true is a matter of debate, but it should be noted that helmets of the style that also originated in the region were worn by various nomadic groups including the Huns, Göktürks, Uyghurs, Tatars, and Mongols.

As they made their trek, later Turkish groups adopted the Persian-style helmets that may have helped inspire the early “spiked helmets” (Pickelhaubes) that emerged in Russia and British-controlled India before making their way to Europe — where the Prussians embraced them with true Germanic enthusiasm. During the early Ottoman era, the helmets further evolved, becoming conical in shape that may be seen as reminiscent of the domes of mosques.

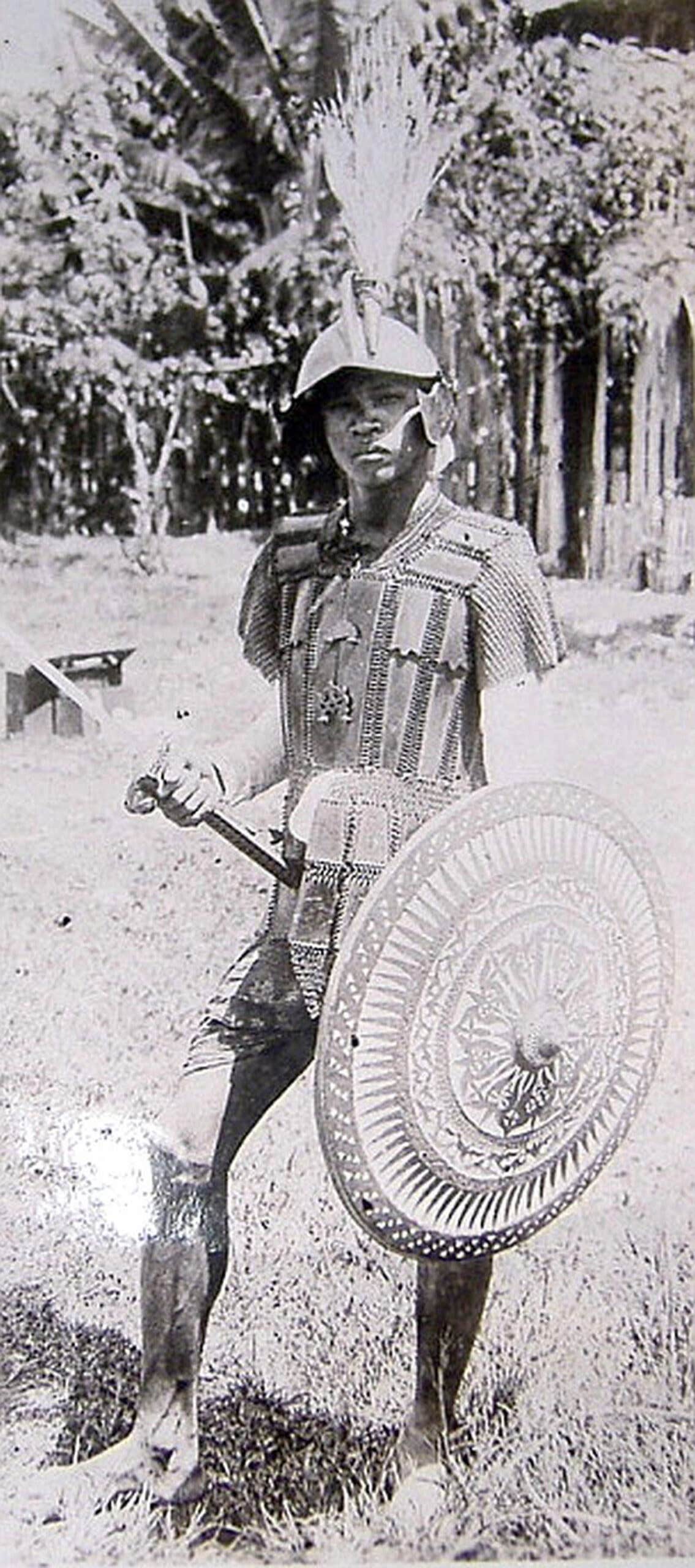

As armor largely — but not entirely — disappeared from the European battlefields in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Ottoman helmets also gave way to lighter headgear, including the “bork,” a tall felt hat that was worn by the famed Janissaries, and later to the fez. Yet, some cavalry units, notably in vassal states in the Balkans and in semi-autonomous Egypt continued to wear breastplates and ornate steel helmets — a practice not that dissimilar from what was seen with the heavy cavalry of France, the UK, and the unified Germany in the latter decades of the 19th century and even in use during the early stages of World War I. However, by the end of the 19th century, helmets were rarely seen in the Ottoman military.

World War I and the Turkish Steel Helmet

The first time many American militaria collectors in the post-World War II era likely even knew that Turkey used a steel helmet during “The Great War” was only after the publication of the late Floyd Tubbs’ book Stahlhelm: Evolution of the German Steel Helmet in 1971. The single page that Tubbs wrote about the Turkish helmets is notably missing from the 1990 reprint that Dr. Robert Clawson helped prepare — and for good reason.

Tubbs, who this author as a very young collector did have the pleasure to meet on a few occasions in the early 1980s, wasn’t known for doing the best research. That isn’t to disparage his memory, but just stating a fact. More importantly, his work inspired many a helmet collector including me.

Yet, the particular passage is an example of “misinformation” that was spread by collectors. It explained the German-made helmet’s “front visor was missing,” and “this was for religious reasons. It allowed the Turk to touch his head to the ground when praying. They sacrificed the safety feature and gained values needed for their sacred tribute.”

Before Dr. Clawson passed away in 2014, I had a chance to talk to him about the removal of the erroneous information and asked where Tubbs may have discovered this detail. Clawson told me, “Floyd was a great guy, he was passionate about collecting, but he obviously didn’t know everything. He likely guessed and then accepted it as fact.”

The truth is that Floyd Tubbs may have also confused another German-made helmet (a point to be addressed), but he also didn’t know quite enough about Islam either. Throughout the past 1,500 years, soldiers of the Muslim faith have been encouraged to maintain their religious practice of prayer — which includes touching the head to the ground — but it could be adjusted as the situation dedicates.

“The Qur’ān enjoins the performance of prayers even during military operations (Q 4:102), albeit in a modified way. This type of prayer is called Ṣalāt al-Khawf, ‘the prayer of fear,’ and it has been described as a uniquely Islamic prayer,” Aram Shahin of James Madison University explained in his study Ritual & Religion in the Medieval World.

Though the Ottomans had undergone significant changes in the late 19th century, they didn’t abandon Islam as the state religion. Far from it, and during the First World War, the Ottoman Empire even issued a fatwa declaring a “Jihad” against the Allies, which further encouraged religious devotion among soldiers. Part of the hope of the Central Powers was that the indigenous peoples under French and British control in Africa and notably India would rise up against their colonial masters. As anyone who has seen the film Lawrence of Arabia may know, it was the Ottomans who faced such a revolt, from the Muslim Arabs that had been under the Sultan’s thumb for centuries.

Yet, just as in the Middle Ages, soldiers of the Islamic faith would pray when the time allowed. Moreover, helmets could be removed where and when the situation allowed, so no one expected the Ottoman infantryman to stop fighting to pray at a prescribed time with a steel helmet on his head. Thus old Floyd was guilty of trying to find an answer for the missing visor, but again there is more to the story.

A uniquely Turkish design

Tubbs wrongly assumed the visorless helmet, which will be described in detail, was meant for the Turks. It was probably an honest mistake, and he was far from alone in making it. Other books of the period suggest the helmet was Turkish – but Tubbs seems to remain the earliest to jump to such a conclusion.

What we know now is that the German-based Eisenhüttenwerk Thale produced 5,400 of the Model 1918 “Full Visor” helmets for the Ottoman Empire. The question is why, and helmet collectors have also asked it for decades, and it does seem reasonable to ask. Germany was already under intense pressure, and modifying the helmet design seemed impractical to say the least.

The best answer offered over the years is that may have come down to uniformity, and maintaining the Turkish identity. There is a case to be made for this hypothesis.

The Ottoman Empire was already in a period of modernization and transition when the First World War broke out. More importantly, it had been a long-standing ally of Great Britain but only switched to an alliance with Germany in the years immediately before the First World War. Several factors came into play, including changing alliances in Europe. On one side, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy made up the Triple Alliance while the UK was part of the Triple Entente – the loose diplomatic alliance with France and Imperial Russia – on the other side. Along with Britain’s growing influence in the Middle East, including its support for Arab nationalist movements, that likely made the Ottoman leadership wary of British intentions. Germany also promised to build the Baghdad Railway, which could have provided a crucial transportation link throughout the Ottoman territory.

Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II made a famous visit to the Middle East in 1989, during which he showed support for the Muslim peoples — although that was likely just to stir up trouble within the aforementioned British and French colonies. Turkey entered World War I in late October 1914, but the Sublime Porte — the name by which the Ottoman government was known at the time — sought not to take on too much of a German identity.

By the time the helmets were introduced in 1918, Austria-Hungary had become essentially a satellite state of Germany, and the Ottomans may have sought to maintain their independence, including having a more unique steel helmet. That latter point is my personal speculation, and I don’t claim it as absolute fact, but it is based on those other points.

As collector/researcher Mark Dillenbeck described on his Steel Helmets of the World Wars website, “A theory that seems plausible to me is that the Ottomans wanted a helmet that reflected their traditions and was distinctive. The design of the Turkish M18 may have been chosen because it resembled a popular sun helmet worn by officers and NCOs.”

Dillenbeck is referring to the Ottoman’s kabalak and bashlyk, which author/researcher Dr. Chris Flaherty described as being adopted following the 1908 Army reforms. The latter hat, also spelled “basklik,” has become known as the “Enver Pasha Helmet,” after the Turkish war minister who supported close ties with Germany. Both forms of headgear, which were meant to replace the fez, were worn by the Ottoman troops and became an iconic symbol of the Turks in the First World War. Few kabalak or bashlyk have survived and most that show up today are fakes (so be warned)!

In a 2011 article for the UK-based The Armourer, Flaherty wrote, “The M1909 (Ottoman Turk) ‘Kabalak’ or ‘Enveriye’ helmet was designed as a cane-wood frame with two lengths of cloth wrapped about it. This traditional form of Anatolian folk headgear underwent a radical transformation during the war, and this coincided with the introduction of the German M16 converted helmet.”

According to the research from Flaherty and Dillenbeck, all 5,400 of the Turkish helmets were marked “ET” along the size stamp, which was 66. No other sizes were made. All of the helmets feature a German Model 1918 liner with white liner pads and carbine clip chinstrap attachments.

In his article, Flaherty explained that the Ottoman forces also received an unknown number of German M16 helmets that were cut down (the aforementioned converted helmet). These were reportedly provided to Enver Pasha’s forces before the production run of 5,400 specially-made helmets, but Flaherty could only speculate on why the alternation was done. It is possible a handful were made — with the conversion completed either in Germany or perhaps in Turkey to serve as a template for final design. There remains speculation in collector circles whether Flaherty is correct about the cut-down helmets ever being made, as it would seem to be an unnecessary modification during wartime. In this case, I will not weigh in on the matter and only add that provenance would be required for me to accept that any German M16 that has been cut down was modified during the war and was supplied to the Turkish military.

To further complicate the issue, Flaherty has noted that fakes of the Turkish M18 have been made in recent years, with most coming from cut-down Czech M20 helmets.

The full visor debate

Today the Turkish helmet is known as the M18 “Full Visor,” which is really just a collector term. It doesn’t appear that Eisenhüttenwerk Thale had any specific designation, nor did the Turks.

However, in his book, Tubbs described a Full Visor Helmet. In both editions of Stahlhelm, it is noted, “Another helmet variant appeared during the war when the full, or high, visor German helmet was produced and issued to troops,” but added, “The length of the visor from the face remained the same; it was only the extra space by the forehead the was increased.”

That description doesn’t quite sound like the M18 Turkish helmet, yet the illustration does sort of resemble it. The book also features two distinct versions of the Turkish helmet in the photo section at the end, including of a visorless and a “rolled edge.” We can speculate that Tubbs may have confused the descriptions of the Turkish M18 “Full Visor” with the German variant that he also explained, “was manufactured for such a short period, it has become extremely rare.”

Authors Michael J. Haselgrove and Branislav Radovic also mention such a helmet in their book The History of the Steel Helmet in the First World War: Volume One.

“This was a variation in which the visor sloped forwards from the top of the helmet at an increased angle. This may have been an experiment to allow greater clearance between the wearer’s forehead and the helmet to allow the more convenient use of a gas mask,” the authors wrote. “Alternatively, the increased angle at the front of the helmet may have been an experiment to ascertain if projectiles would be better deflected. Very little is known of these helmets.”

That book doesn’t include a photo, but an image is present in the late Ludwig Baer’s The History of the German Steel Helmet 1916-1945, where it was also described as possibly tested for use with a gas mask. Whether any of that is completely factual is unknown, but we can assume some collectors may have seen or even owned a few of these helmets. It is impossible to know if that is the helmet that Tubbs was referring to more than five decades ago or something else.

The visorless helmet that isn’t Turkish

What is known is that Tubbs was convinced the visorless M18 German helmet was produced for Turkey. As previously stated, a photo of one of these is included in Tubbs’ book, and identified as Turkish. With it entirely lacking a visor, it would seem it could be possible to almost touch the head to the ground while wearing it. Again, it is likely that Tubbs tried to find an answer for why the visor was missing and came up with an answer.

According to Flaherty, any suggestion that the visorless helmet was intended for the Ottoman Empire is “totally incorrect,” and he added, “It also mistakenly links the helmet design with the 1247 (European date of 1832) decree of Sultan Mahmud II declaring the Fez to be the Ottoman Turkish national headdress.”

In recent years, it has become accepted that these helmets were likely used by the Freikorps following the end of the First World War. Details regarding the visorless helmet may have even confused Baer, who in his book described them as Turkish! There has been no solid evidence the visorless helmet was ever meant for Germany’s Ottoman allies.

The exact purpose of the helmet variant isn’t clear, but the currently accepted theory is that the visorless helmet was developed for use in the early German tanks. The war ended before these made it to the frontlines, but were used by the paramilitary units immediately following the end of the war.

International Military Antiques (IMA) sold a replica of these, which were described as “Essentially a German M-1916 Helmet with the peak removed, this helmet is unmistakable and nothing else resembles it,” while also citing the 5,400 that “were manufactured in Germany for shipment to their ally Turkey.” This confused the two helmets — and likely a few collectors were also confused as a result!

{Special thanks to Mark Dillenbeck and Gus Bryngelson for their insight in this article. Thanks are also due to Chris Flaherty for his past assistance and research into Ottoman headgear.}

*As an Amazon Associate, Military Trader & Vehicles earns from qualifying purchases.

Interested in military helmets? Here are a few more articles for your reading enjoyment.

https://www.militarytrader.com/militaria-collectibles/a-look-at-the-experimental-british-sun-helmets

Peter Suciu is a freelance journalist and when he isn't writing about militaria you can find him covering topics such as cybersecurity, social media and streaming TV services for Forbes, TechNewsWorld and ClearanceJobs. He is the author of several books on military hats and helmets including the 2019 title, A Gallery of Military Headdress. Email him and he'd happily sell you a copy!