Just Sign on the Dotted Line

I have been giving a lot of thought lately to the cult of collecting “personalities”. I didn’t realize I had been pondering it so much until one of my regular…

I have been giving a lot of thought lately to the cult of collecting “personalities”. I didn’t realize I had been pondering it so much until one of my regular authors offered an article about collecting autographs of people represented in a recent hit WWII mini-series. My reaction to the article was, “This isn’t militaria...this is just trying to grab a piece of someone else, no matter what the context of the signature.”

This isn’t new...people have been collecting the signatures of the famous for a couple of hundred years. Gathering the signatures of Revolutionary War generals and politicians was popular before the Civil War. During the Rebellion, people eagerly sought the signatures of generals.

As a kid, I briefly dabbled in the hobby when my brothers took me to the Minnesota Vikings’ training camp and I waited for Bill Brown, Dave Osborne, Carl Eller and Alan Page to sign a scrap of paper. Possessing their signatures somehow made me feel “closer” to them, though I actually didn’t learn a thing about the game or the players from their hastily scrawled names.

And therein is the essence of autograph collecting—trying to be close to someone who really doesn’t know you exist. An autograph doesn’t impart any information about history (apart, possibly from the style of writing utensil and paper used in the creation), but it can be a conduit for a fascination about history. Holding a clipped signature written by General George Pickett doesn’t teach a person a thing about the general or his penultimate moment at Gettysburg. However, it does pique the holder’s fascination, and perhaps will spark the desire to learn more about the signer’s role in history.

But how did the autograph article opportunity churn my brain to ponder my own collecting habits?

Recently, I have had the opportunity to add an interesting piece of WWI Tank Corps history to my collection. The item, on its own, would normally be an $800 acquisition. It’s just a common item that every tanker had and represents a segment of history about the birth of the Tank Corps. However, because the item belonged to a famous tanker, the price is a few thousand dollars. I have wrestled with the acquisition for a week now.

On the one hand, the piece does fill my personal collecting mission statement: “Acquire and display items that tell the history of the birth of the Tank Corps and its combat history in the Great War.” But any similar item—without the fame connection—would tell that story. The question I have been asking myself is, “does the Tanker’s fame impart any more about the early history of the tank corps?” If the answer is yes, the follow-up query is, “Is his story worth several thousand dollars?” This is a tough one, but the answer is somewhere near the core of collecting militaria.

Why do I collect?

All of us who collect this stuff, whether autographs, medals, uniforms or tanks, in some part, are surrounding ourselves with representations of the deeds of others. Having a roomful of Tank Corps uniforms does not make me a WWI tanker any more than the reenactor who pulls on his reproduction uniform and slides into an actual FT-17 tank. But both approaches do impart some sense of the original tankers’ experience.

My collection fulfills many roles in my life, however. I display the collection at my office, and find myself, through the course of the day, turning around in my chair and looking at my various exhibits. I approach the collection the way I was trained as a museum professional...I look for artifacts that will spark a dialogue. Each exhibit tells a facet of the AEF Tank Corps story, and as such, they tell the stories of personalities and experiences.

Twenty tunics with tank corps insignia don’t tell the story of the Tank Corps any better than the single uniform worn by Sgt. Robert E. Hayes, a tanker in the 302nd Tank Bn. looking at a row of tunics, I have the reaction of a hunter/gatherer looking at a row of trophies. Looking at Sgt. Hayes’ uniform, I think of his trials and tribulations cooped up in a hot MK V tank training in France.

While staring at Sgt. Hayes’ uniform and accouterments this morning, it dawned on me—autograph collectors aren’t that much different. They simply use the signatures as the conduit to ponder the experiences of the signers.

Seeking Advice

In the course of contemplating my dual-dilemma (a: should I publish an article on collecting “celebrity” autographs and b: is a particular relic for my collection worth spending several extra thousand dollars simply because it was associated with someone famous), I sought the opinions of a couple of dealers and a museum curator—all three people I deeply respect.

The discussion about the autographs boiled down to their place in the realm of militaria. To many, collecting autographs is like “counting coup”...it doesn’t impart anything about history but, rather, establishes a presumed relationship between the historic figure and the collector.

But, the discussion led to there being different types of autographs. We labeled the first type “convention autographs”. In this group are the autographs obtained in a setting where the “celebrity” sits and signs anything from photographs to ladies’ breasts. You see this at many of the larger militaria shows. There is no shortage of Jeeps with dashboards signed by the “Gunny”. These are all what we considered to be “convention signatures”. They are produced long after the person’s rise to celebrity.

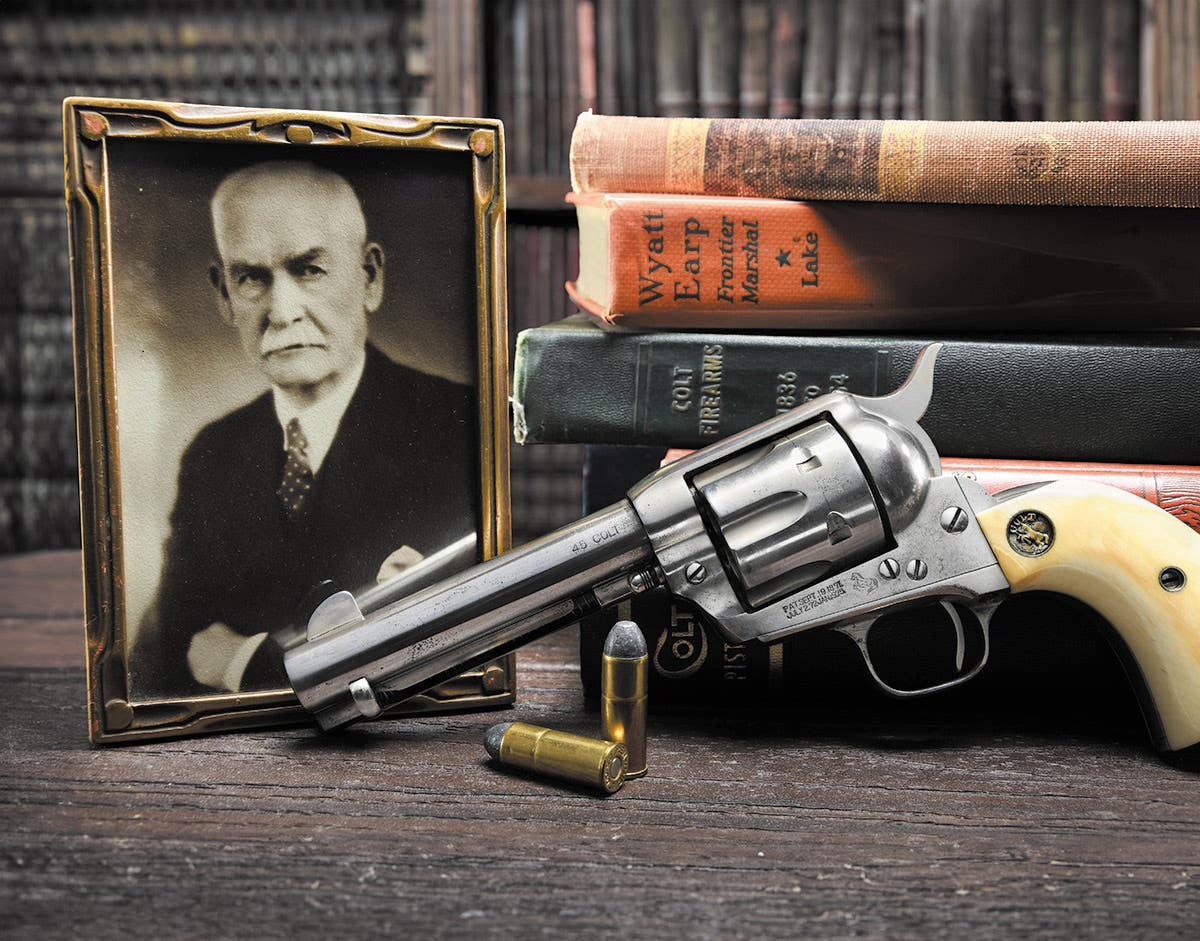

The other group we labeled “contemporary autographs”. These are signatures that were written contemporary to the period in which the personality elevated to “historic” status. This led to a discussion of the value of a clipped signature versus a signature on a document that actually imparts a sense of person’s role in history.

As an example of our thought process, we chose signatures written by Shifty Powers—an unknown-to-history WWII paratrooper until Stephen Ambrose interviewed him for his book, Band of Brothers. Shifty’s signature on a black-and-white photo obtained at the Show of Shows would be a “convention” autograph. His signature on a 1944-dated delivery shipment for ammunition near Bastogne would be a “contemporary” autograph. And finally, Shifty’s signature on a 1959 cancelled check falls somewhere in between.

We concluded that that any article for Trader would have to clearly make these distinctions. Why? Because the “convention” autograph won’t hold its value beyond our generation. When we are dead and gone, the excitement about the Band of Brothers will subside and fade. They are not characters that will stand the test of history as opposed to the likes of Montgomery, Bradley and Eisenhower, who will continue to command interest. I hate to sound so shallow, but the “Band of Brothers” are like the Beanie Babies of militaria. They are easy to like, quickly identifiable and if one scrambles, one can “own” them (by acquiring autographs). Of course, I don’t want to imply that the soldier’s contributions aren’t important to history; I am just saying that their fame (and the attempt to buy and sell items related to them) is more of a “fad” than a collecting genre.

Here’s another an example, this one a bit closer to home. A signature of Bernhard Graf who fought with Company F, 2nd Minnesota Infantry, has little, if any value to Civil War collectors. To me, because he was a great-great uncle, it has some personal value...it establishes a sense of connection to an otherwise unknown figure of Civil War history. A letter written by him from Nashville in 1864 commands a whole lot more interest (and would have a broader collector appeal) than his signature on a probate form from 1888 (which would have minimal collector appeal) and even a whole lot more than just a clipped signature written soon before his death in 1900 (which would have no collector appeal).

The antithesis to these examples, of course, would be Sergeant Alvin York. His signatures have sustainable value that follow the three tiers of contemporary, somewhere-in-between, and convention. But the values are sustained because he is a recognized and decorated hero, unlike Shifty or Wild Bill of the “Band of Brothers”, who are just soldiers who found their 10 minutes of fame because an author elevated them to the big screen.

So? What’s the Price of Fame?

After all this pondering and consternation, one would expect that I had reached conclusions to my dual-dilemma. I was reminded of the strength of the “identified” artifact (one which is directly associated with a particular soldier) versus the unidentified. When I know the identity of the tanker who wore a particular helmet or uniform, I am willing to pay more. For some reason, that sense of personality imparts a stronger connection to the history. Whether I admitted it or not, I collect “celebrity”.

So, my former harsh opinions about autograph collecting began to soften. I am willing to admit that it is a legitimate segment of military collecting (though I continue to insist a Jeep signed by the “Gunny” is no more valuable than an unsigned quarter-ton in the same condition!).

What about my big purchase? Well, I have concluded that the several thousand dollars for the connection to a Tank Corps celebrity is justified. Now the real struggle begins—paying for it!

Keep finding the good stuff,

John Adams-Graf

Editor, Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine

[Note: Signature not worth the paper on which it is written]

John Adams-Graf ("JAG" to most) is the editor of Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine. He has been a military collector for his entire life. The son of a WWII veteran, his writings carry many lessons from the Greatest Generation. JAG has authored several books, including multiple editions of Warman's WWII Collectibles, Civil War Collectibles, and the Standard Catalog of Civil War Firearms. He is a passionate shooter, wood-splitter, kayaker, and WWI AEF Tank Corps collector.