Hitler desk set comes to market

Used during the signing of the Munich Pact

Hitler signing the “Munich Pact” with Mussolini, Chamberlain and the French leader. The set is visible on the desk.

By Peter Suciu

There is an old saying that “the pen is mightier than the sword.” In the case of the 1938 Munich Pact, which was the agreement permitting the German annexation of Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland, this proved somewhat true. With the stroke of a pen and signatures from Nazi Germany, France, Great Britain and Italy, war was essentially avoided, with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declaring, “A British Prime Minister has returned from German bringing peace with honor. I believe it is peace for our time.” The irony was that this appeasement, as it was called, resulted not in peace for that time but instead merely set back the clock for war. Less than two years later, the Second War World had begun.

At the time of the Munich Pact, Jack McConn was a teenager living in Houston with his family. He couldn’t have imagined that someday he would own the very desk set that in all essence signed away the freedoms of millions of Czechs and Slovaks. And here is where the story of this fascinating piece of history begins. “I really had no idea that I would return home with such an important piece of history,” says Jack McConn, now 87 years old. “I was 21 years old at the time I came across the desk set and I thought it looked like a good souvenir.”

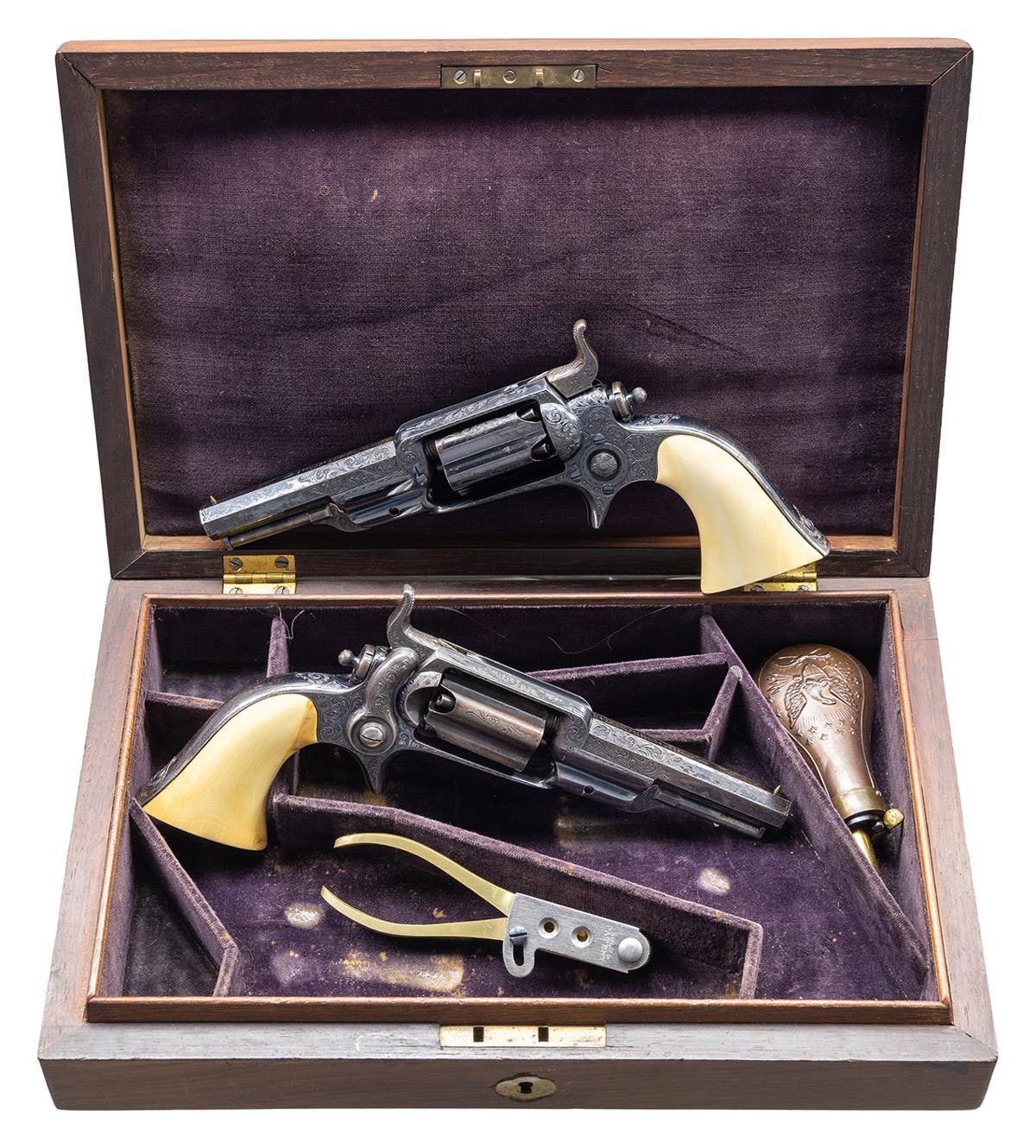

The Adolf Hitler Desk set is a single cast bronze piece, measuring 24” x 13-3/4” x 1-3/4”. It features two inkwells that are 2” in height and a blotter that is 8-1/8” x 4-3/4” x 4”. It features the raised initials “A” and “H,” indicating Adolf Hitler, flanking the Nazi eagle and swastika.

At the time McConn had no idea of the historic significance, either. “Hitler was famous at the time; I guess you could even say infamous at that point. I didn’t know what it was but it was a heck of a good souvenir.” For McConn, as with the millions of other young American GIs in uniform serving far from home, he didn’t intend to be a souvenir hunter. He just hoped to survive and make it home in one piece. And as with the rest of the Greatest Generation, he wasn’t thinking Munich Pact or even the reasons for the war when his story in the army begins. “I was in the infantry and I have a lot of stories about that,” says McConn, and the former foot soldier isn’t bragging. His record includes a battlefield commission, and numerous awards including the Silver Star and the Purple Heart. To the latter he remains modest. “It was just a scratch. I saw guys get a lot worse.”

McConn served in the 7th Army, and landed in Marseilles in the South of France in September of 1944, following Operation Dragoon. He later ventured up the Rhone River and finally crossed the Rhine River, taking part in the breaking of the famous Siegfried Line. “We went through a lot of battles,” says McConn, “and I got lucky in more ways than one.”

He tells one story that, while still a sergeant, he faced incoming mortar fire and a shell went off very near his foxhole. “The shell went off and something hit me. I just laid there, I thought I had a chest wound and it really hurt. But then I got up and ran and made it to a barn.” He says that his CO at the time asked what the hole was doing in my jacket. “He reached in and took out a big piece of shrapnel.” McConn says it was a gift from an ex-girlfriend that saved his life. “She gave me a prayer book that had a steel cover. It just happened to be in my pocket.”

Fate turned its hand again, when McConn and his buddy were informed in early December 1944, that they’d be shipped back to Georgia and receive officer’s commissions. It turned out instead they were taken about 60 miles back and received a 10 day “deal on how to be an officer.” McConn says just as he received the official commission, the Germans counterattacked. “The Germans tore through where my unit had been, and I can’t imagine what those guys faced.” After the turning of the tide with the offensive McConn served out the war as Lieutenant, crossed the Rhine, cut the Autobahn and made it to Hitler’s headquarters in Munich. McConn, along with other American GIs, was quartered after the war in the building known as the “Feuerbau,” located on the Konigsplatz in Munich.

Hitler’s office had been on the second floor of the building, but had been stripped clean of virtually all the furnishings, but not because of American soldiers. It was more likely because of American bombers. When one soldier in his outfit showed some personal effects that belonged to Hitler, McConn came across a large bronze desk set that was found in the cellars of the building. It featured the raised letters “A” and “H” as well as the Nazi German eagle with swastika. As a young First Lieutenant in Company G of the 179th Infantry, 45th Division of the United States Army, McConn decided to ship the item home, making a wooden box for it. “I mailed it to my dad in Houston, and miracles of miracles, it got to him.” Considering that today it is hard enough to send a holiday care package to a friend without fear of damage, it is amazing that the piece was received without so much as a scratch. “I don’t remember how it was packed, but my best recollection is that it just it in the box.” McConn adds that the fact that it was bronze made it all the harder to damage. He also says that his father likely had no idea what to expect, either.

Detail of one of the two distinctive boxes that aided in the identification of the set as being the one used by Hitler, Mussolini and Chamberlain when they signed the Munich Pact.

The box with the desk set was sent in late summer of 1944, and McConn was soon reunited with it, making it home in October of the same year. The set resided in his father’s office for a number of years and, after attending law school, McConn’s father suggested his son take it back, which he did. “There had been some stuff disappearing in the office, so I took it home.” All this time McConn had no idea of the value or importance of this particular item. “After some years, I saw a newsreel about the Munich Pact. In it there was a shot of Hitler, Mussolini, Chamberlain and the French leader and they were signing on the same desk set that I had in my house! That was pretty amazing.” At that point McConn realized its importance. “I decided then that it had to be safely stored and I looked around and found a bank vault that was of a pretty good size where it could be safe.”

Now at 87 years old, Jack McConn says the time has come to sell it, and hopefully go to someone that can display it better or an institution where others can see it. Military dealer Craig Gottlieb agrees that this is a truly significant piece. “Hitler did to Europe in one afternoon what it would have taken years to do in combat.” And both McConn and Gottlieb agree it would be better not to merely sit in a bank vault. “While it’d be interesting to watch a collector pony up the coin for this artifact,” says Gottlieb, “I really do believe it should be in a museum. It’s the quintessential symbol of appeasement, and with that topic on the tongue of every policy wonk in the world, after 9/11 and the world’s relationship with Islam, it’s a very timely artifact.”

It is also agreed that it is the definition of a “one-of-a-kind item.” To that end Gottlieb admits that the only way to value such a piece is to auction it. He estimates that it could go between $750,000 and $1 million. And yet, McConn doesn’t see it as winning the lottery. He served his nation and found what he merely thought was an interesting souvenir. No matter how much money it makes, he says he’d like to leave some to his family, but that he’d probably give a lot of it to charity so that from the evil it once did, perhaps today it can do some good.

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN:

*Military Vehicles Magazine

*Standard Catalog of U.S. Military Vehicles, 1942-2003

MORE RESOURCES FOR COLLECTORS

*Great Books, CDs & More

*Sign up for your FREE email newsletter

*Share your opinions in the Military Forum