Emergency Jungle Landing Kit

High winds, bad storms, lightning and birds to name a few. A downed airman who survived a crash or forced landing needed the means to stay alive at hand. If the event happened in a remote area, far from civilization, survival could be a real challenge.

The advent of aviation opened up the world to travelers like never before. Airplanes could place humans over areas of the planet that were previously unreachable because of terrain and/or remoteness of the spot. While aviation greatly increased distances that could be traveled between the First and Second World Wars, the only enemies faced by aviators were environmental.

High winds, bad storms, lightning and birds to name a few. A downed airman who survived a crash or forced landing needed the means to stay alive at hand. If the event happened in a remote area, far from civilization, survival could be a real challenge.

Common sense and weight and space considerations dictated the type of survival items carried by aviators. Space and weight concerns forced aviators to pack just the essentials. Hard experience, relayed by those who survived, taught others what to pack and not pack for survival. Army aviation was taking all the notes it could. Aircraft were easy to replace. Pilots were not.

Through the 1920s and early 1930s, Army pilots would scrounge, trade, or requisition items that they knew increased their chances of survival in the unfortunate event their aircraft went down. Items came from on-base stores, the Navy, and commercial sources. Because improvised survival kits often proved inadequate for their intended purpose, the Materiel Division’s Equipment Branch at Wright Field began research and development on survival equipment.

EMERGENCY JUNGLE LANDING KIT

It was not until 1934 before any U.S. air unit made an official request for an issue survival kit. Air Corps units based at Albrook field, Panama Canal Zone, requested a parachute back pad that would contain items deemed necessary for survival in the jungle.

The new kit was designed to be attached to the parachute harness. It was intended to have all the items needed for jungle survival in pockets inside. When issued, it was known as the “Emergency Jungle Landing Kit.”

Designed to attach to the parachute harness and fit under the wearer it was made of brown, heavy, cotton duck and looked a little like the body of a guitar or odd banjo with a zipper around three sides and flaps at each end with straps to affix it to the harness. The side away from the wearer was stuffed with horsehair padding and the side that the flyer sat on had an approximately two inch thick pad of heavy felt that had pockets cut out to accommodate the survival gear. The 1934 kit had the following items inside.

1.) One “Little” machete. This was the actual designation given this knife by the Army Air Corps. Three makers supplied the knives for the Army Air Corps, Case, Western and Kinfolks. A very similar knife was made by Collins and issued to Marine raiders (Carlson’s Raiders). Designated the Collins No. 18 machete its similarity has led to some confusion about the name given the survival pack knives.

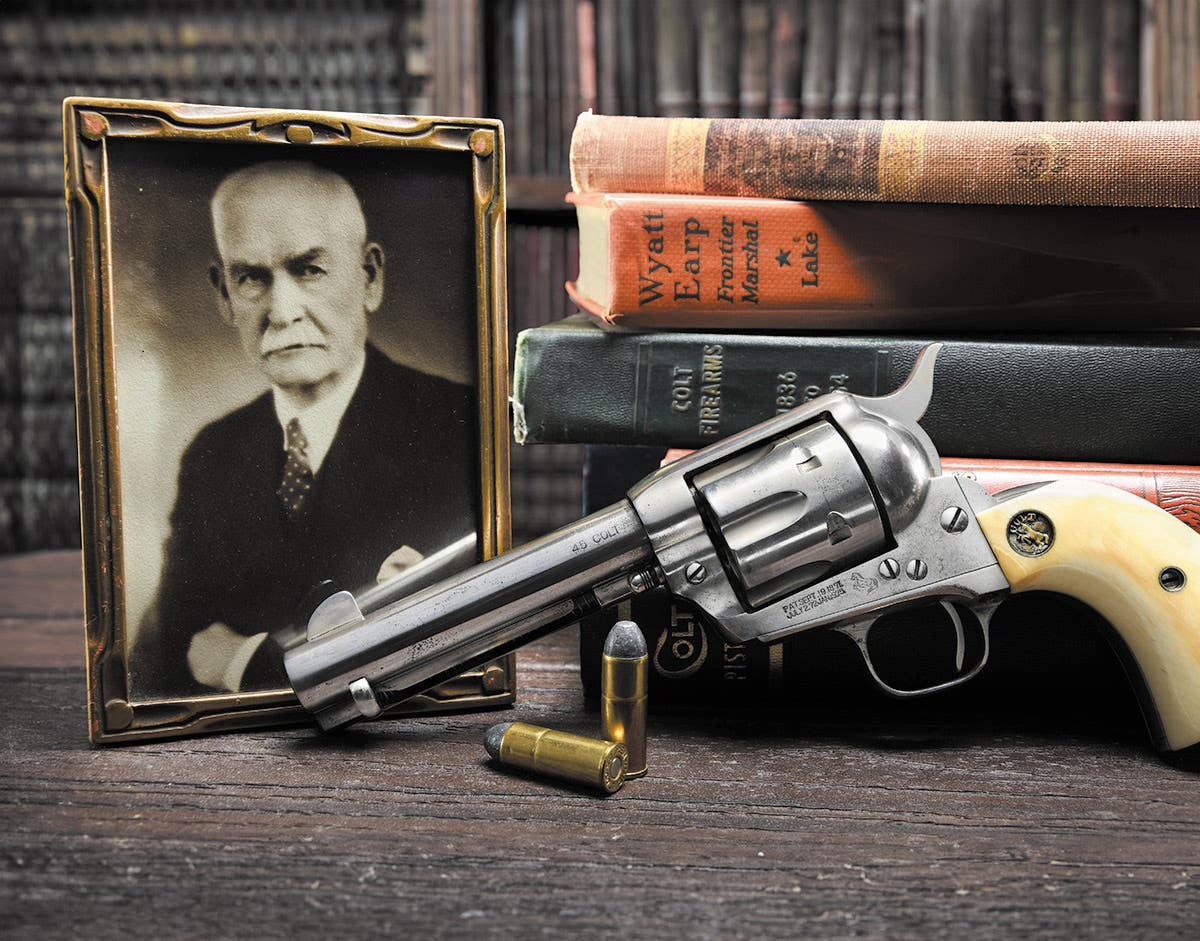

2.) One Model 1911 .45 ACP in a leather holster. Most, if not all, were made by Colt. Twenty rounds of ammo were included.

3.) Two emergency rations.

4.) One pocket compass.

5.) One waterproof matchbox. Contained strike-anywhere matches that were coated to be water resistant.

6.) One vial of iodine. Could be used for water purification or wound dressing.

7.) Twenty five quinine tablets. Stored in a waterproof metal container.

8.) One mosquito headnet.

Nevertheless, only a small number of these “Jungle Survival kits” were assembled and issued for use in Panama and the Philippines. They created problems for tall pilots. Because of their thickness they created problems for tall pilots by causing their head’s to stick out above the windshield into the slipstream.

The “Jungle Survival Kit” shown in this article was issued at New Castle Army Air Base in Delaware in December 1942 or January of 1943. The man to whom it was issued was in the Air Transport Command, part of a team delivering bombers to aircrews fixing to go into combat. According to the retired master sergeant, this was the route they most often took when delivering bombers early in the war. After leaving from the airbase in Delaware, they flew to British or French Guiana, then to Brazil, then to Ascension Island and then, usually, on to Accra, British West Africa or French West Africa. Once in Africa, the aircrews that would serve on the bombers took over the planes.

The “Jungle Survival Kit” pictured in this article is just as it was issued, minus one item. The man to whom it was issued was the same man from whom it was purchased. He was certain the only thing missing was the emergency ration bar. It was chocolate, there was only one and he said it turned to mold many years ago in Florida’s humid climate.

This kit was not issued with a .45 ACP pistol. That was separate issue though the kit was issued with twenty rounds of .45 ACP ammo. Made by the Western Cartridge Company the ammo is labeled “Pistol, Ball, Caliber .45 M1911 ammunition lot W.C.C. 1095.

There are several items in this kit that were not listed as being part of the 1934 kit. One is a medium oil (sharpening) stone made by Bay State. The other is a length of fishing line with five, different sized hooks all carefully placed in a small, watertight tin box nestled in its own deep, felt pocket.

The iodine, matches and malaria pills are each in their own watertight, metal, screw-top container. Two of these containers were made by Marbles of Gladstone, Michigan and the third is an Everdry by the Park Sherman Co. of Springfield, Ill. All three fit next to each other snugly in their own pocket in the felt pad.

The “Little Machete” was made by Kinfolks (relatives of the Case family). It has a brass handguard and rivets, a blade 9 ½ inches long and a black, phenolic resin handle.

The only marking on the kit is on one of the flaps and it says “Property Air Force, U.S. Army N.C.A.A.B. Wilmington, Del.” There is an inspector mark beside the property tag.