Bude: When the British town went to war

On December 2, 1943, the civilian residents of the British seaside town of Bude on the north coast of Cornwall, in the southwest of England, turned out to greet the latest in a long line of visitors to come to their town. They were American soldiers sent to train to be more specific.

On December 2, 1943, the civilian residents of the British seaside town of Bude on the north coast of Cornwall, in the southwest of England, turned out to greet the latest in a long line of visitors to come to their town. Bude had been a popular holiday destination for many years, welcoming tourists who came to enjoy the sandy bay, clear waters and hospitality of the many hotels and guest houses. The visitors arriving that day and stepping off the train at the town’s train station were men of the 2nd Battalion Ranger Regiment, and the locals were thrilled to see them.

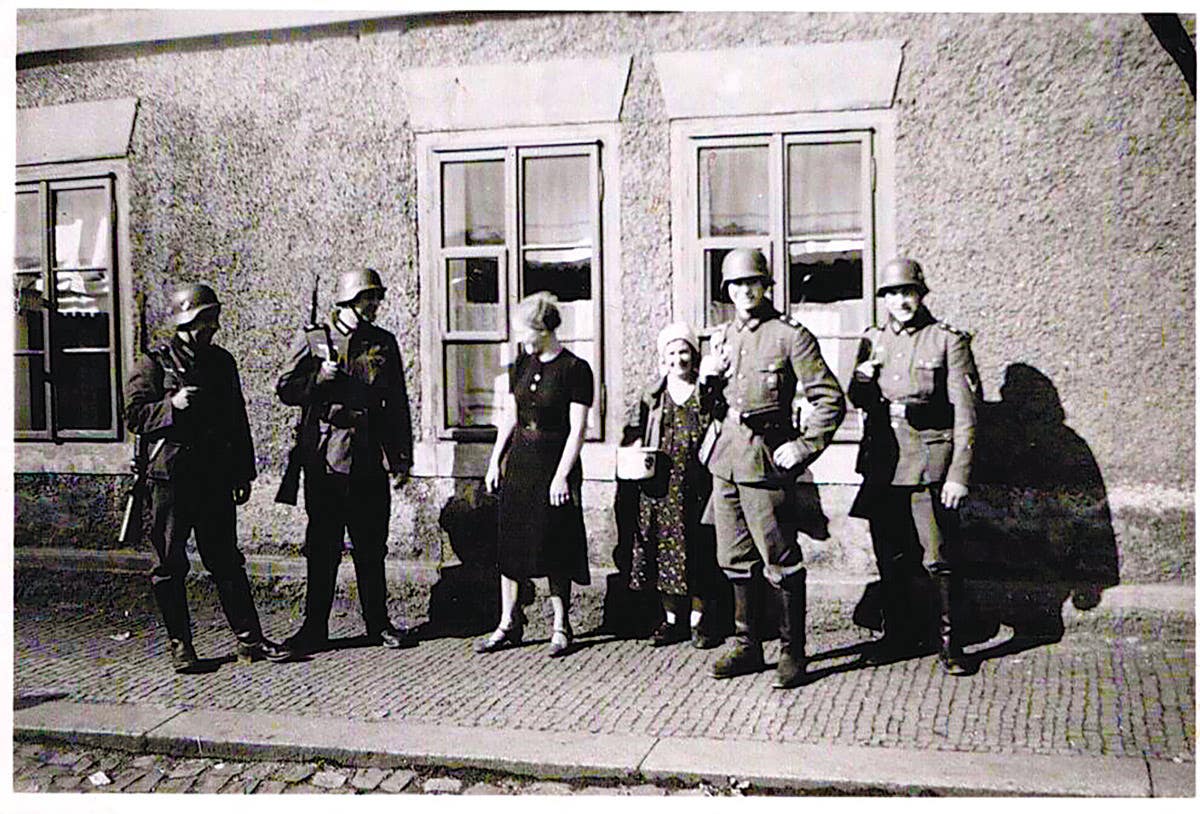

However, these men were not in the town as tourists, but for the very serious purpose of conducting specialist training in preparation for a mission which they knew lay ahead. They did not know any details of the mission, other than they had to train hard. These were not the first American troops to arrive in Bude; the 29th Ranger Battalion had beaten them to it by several months when they descended on the town with orders to trial new equipment and tactics. They were not the last, either, because by April 1944 a further 24 military units would pass through the area for training.

At the time, the town of Bude had a population of less than 2,800 men, women and children of all ages, with each household having members of family serving in the armed forces. Although designated as a training center, Bude lacked one essential element which other training camps had; there were no barracks where the troops would sleep and eat. Instead the men were detailed to households where, as one veteran put it, “…We were to become similar to boarders in these private homes.” The facilities in these family homes were more comfortable and relaxed than they would have been in a barracks, but the men had to work and train hard for the unknown mission ahead.

With so many troops rotating through the town, they would have outnumbered the locals many times over, with each successive unit establishing a great friendliness with their civilian hosts. Living in such close proximity with one another, each learned a great deal about their cultural differences in words such as “gasoline” instead of “petrol”. Civilians heard expressions such as hot dogs, Coca-Cola and “chow” which were unknown in Britain at the time. For their part, the troops discovered the combination of fish and chips with salt and vinegar, for which they developed an appetite and ate in large quantities. Young boys in the town were fascinated by these men in smart uniforms and their strange accents. An affinity developed between the soldiers and the schoolboys, and the children competed with one another to see how many badges they could collect from these visiting soldiers.

The troops of this latest arrival of troops were to be billeted with civilian families in the town and would eat in mess halls at hotels such as the Pengarth and Hawarden, the same as troops posted to the town earlier in the year. The officer’ of the 2nd Rangers used the same mess as other fellow officers, which had been established at the Granville Hotel, overlooking the sea. With Christmas approaching, the troops wanted to put on a special treat for the children of the town and began collecting their candy rations. They decorated a hall with a tree and laid out tables. As they watched the children enjoy themselves a veteran remembered how “it did our hearts good”. This would be the one and only time the troops were able to provide such a treat for the children.

Training for the 2nd Rangers included cliff climbing on the local coastline and abseiling back down to the beach, where they repeated the process day after day. They practiced deploying from landing craft and clearing beach obstacles they would encounter, all the while honing their tactics skills. As the weeks passed, the training intensified and became as realistic as possible. The reason for this was because the 2nd Rangers were assigned to assault a particularly strong defensive position on the Normandy coastline of France at a site called “Point du Hoc” where six pieces of heavy artillery had been installed. The only man in the unit to know details of the target was their commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel James E Rudder, who participated in the training exercises.

On April 4, 1944, the Rangers left the town, taking with them many fond memories. In a note dated two days earlier, Lt. Col. Rudder sent a personal message of thanks to the residents of Bude with each household receiving a copy. In it he expressed his “…appreciation for your kindness to the men of my command who were billeted with you during our stay in Bude. I know that I voice the opinion of everyone of my organization as well as the parents of these men when I say thank you”.

With that, they were gone.

Some of the troops who trained at Bude did return many years later and today there is a memorial on a hill overlooking the town. For its part, the town of Bude has never forgotten the experience and this year the community held an over the weekend of Sept. 15 to 17, to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the arrival of U.S. troops. Re-enactors, vehicle owners and enthusiasts descended to present a series of static displays to show collections of items from the period, from bicycles to GMC trucks. A heritage trail had been created around the town with buildings used by U.S. forces being marked with a special blue plaque and a QR which could be scanned for more details.

On the beach, groups of re-enactors demonstrated a training exercise to show how obstacles were dealt with by combat engineers. The participants edged forward towards the face of cliff, where a concrete pillbox remained from the war and had been used to train the troops. Along the cliff a local group from an outdoor pursuit club gave demonstrations of abseiling down the cliff face in the exact spot where the 2nd Rangers had practiced. It was all very thrilling and told something of the story of the part the town played in WWII.

Many of those who were children all those years ago have sadly either died or moved away, but the commemorative display was a fitting tribute to all those who lived in Bude 80 years ago. Apart from different shop fronts and some buildings being demolished, the town has changed very little over the years. The blue plaques outside buildings and the Ranger memorial serve as a lasting tribute and as we approach the 80th anniversary of D-Day these reminders will be even more poignant.