Being There: The military life of WWII soldier Ted Weber part III

The final WWII chapter for soldier Ted Weber

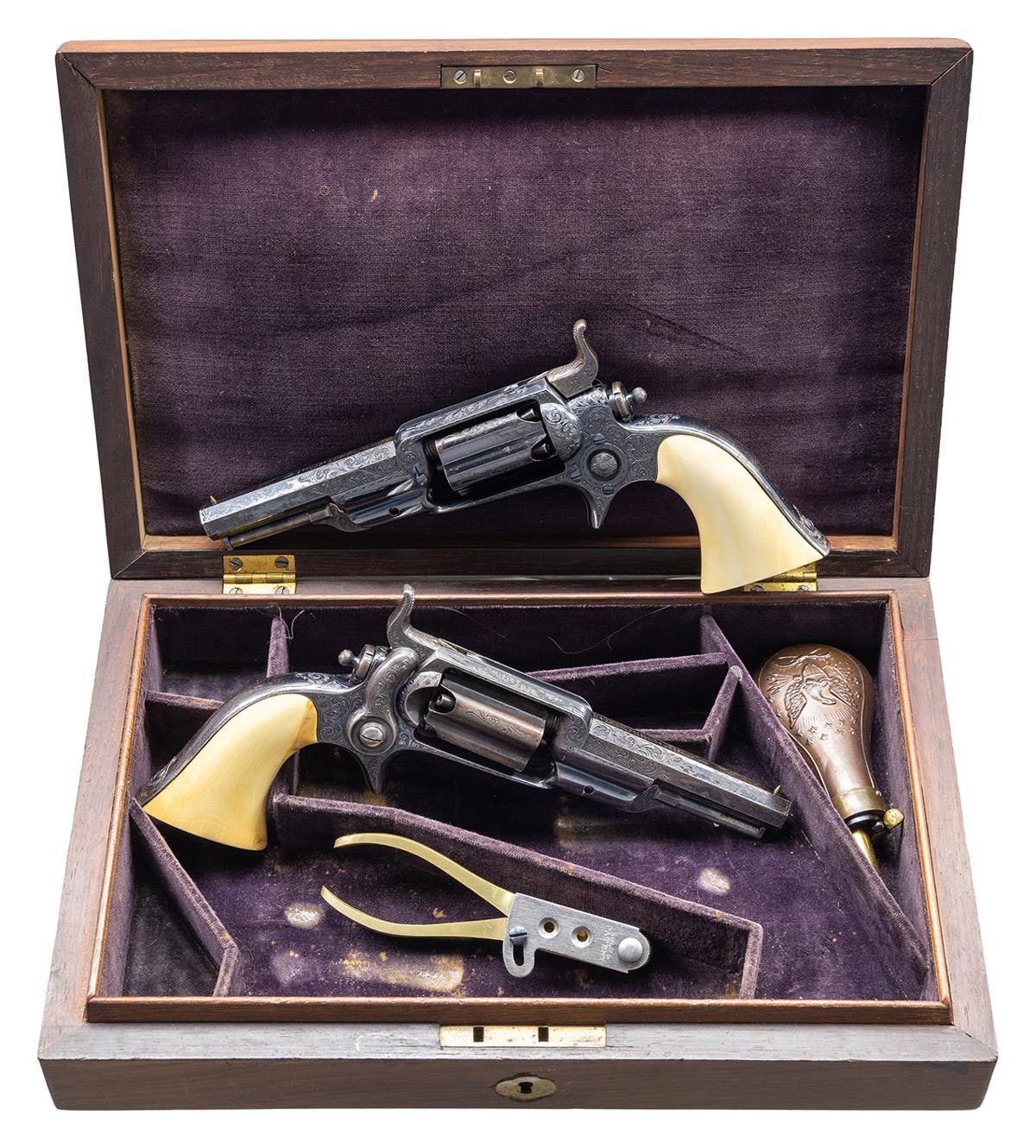

AUTHOR’S NOTE: One of the articles from Ted Weber’s estate following his death was a large steel trunk containing a virtual time capsule from his 3 1/2 years in the U.S. Army Air Corps during WWII. Included in the cache were his uniforms, a few captured enemy souvenirs, over 600 personally taken photos, another 500 or so commercially sold pictures, and letters of correspondence with his friends and family. The crowning piece of the collection were his diaries: day-by-day descriptions in detail from his entry date of Jan. 7, 1942 (one month after U.S. forces were attacked, causing America’s entry into the war) through much of his time serving in the African and European theaters as a B-24 armorer. Weber’s diaries provide a historical “right there” perspective; describing his experiences of mundane training, constant relocations, tedious boredom and sporadic hardships intermixed with the sudden terror of enemy bombing and horrific air crashes during his time with the USAAF 345th squadron, 98th bomber group, serving in WWII.

Writing in his diary during World War II, Theodore Weber, a 23-year-old sergeant armorer in the U.S. Army Air Force, had recorded his experiences of traveling from base to base across the Middle East, the destruction he saw left behind from countless battles, and the aircraft and lives lost in the 345th B-24 squadron. A series of back-to-back missions over Egypt, Sicily, Italy and Austria had taken its toll in both men and machines. Weber was devastated by the loss of “Semper Felix”, his assigned plane, and her entire crew during the Ploesti Raid in August, 1943. With the death of his friends and their plane, he now concentrated on work, keeping his men busy as the squadron’s B-24s continued to bomb the Axis installations in Europe.

After “Semper Felix’s” loss, Weber’s new plane was “Benghazi Express”. This was short-lived, however, since even though “Benghazi Express” had several successful sorties, including shooting down a Nazi plane, she and “Chief” crashed when landing as they returned from their last mission. The two planes were followed in later by “Black Jack”, who landed successfully, but was shot full of holes from the stiff Nazi air and ground defenses.

The news came out on Sept. 8, 1943 that Italy had surrendered, but there wasn’t much time for celebrating at the base. Weber had worked briefly on “Cielito Lindo” before being assigned as head armorer on “Jack Frost”. Here again he cleaned, repaired and test fired the guns, always enjoying the last step if they went up for a test flight. Orders came to move again, and Weber, the other soldiers and their equipment were loaded onto trucks, moving slowly along miles of the now familiar downed planes, burned vehicles, blown-up tanks, minefields and haphazard cemeteries. As they passed lines of pitiful-looking Italian prisoners walking alongside the road, some of the U.S. soldiers threw “K” cigarettes to their former foes.

The convoy passed Ajdabiya, El Agheila, and Sirte as begging Arabs called for anything that the soldiers would toss to them. The trucks stopped close to Tripoli, where Weber and several comrades obtained a four-hour pass to visit the city. They found it to be old and poor, but they managed to procure some local wine from some of the semi-friendly natives that had remained. The next day they passed Zuwara and entered Tunisia. Their truck broke down, the rest of the convoy leaving them behind to catch up the next day. As they waited for the repairs to be made, Weber and a few other soldiers explored the remains of a nearby Roman colosseum and searched a local village for more wine.

Back on the road, they passed through the city of Hergla and then to the Enfidaville camp. The flat desert landscape proved as inhospitable as the other places that had been home to the 345th. The nights in the lightless sea of tents and airfield again proved treacherous when Captain Wilbur ran his jeep into a B-24 named “Hot Rock”, causing severe damage to the fuselage and tail section.

Once the men and equipment were readied, things continued at a rapid pace with sorties into Italy and Austria, causing stress and fatigue for both combat and ground crews. General Doolittle took over command of the 98th group and immediately sent out orders that irritated many of the seasoned troops. New rules of conduct called for soldiers to take off their caps when going into a mess hall and wear ties while on leave. Weber heard a rumor that Doolittle, when assuming command, had agreed to take their equipment, but not the men since they were “too worn out”.

In Tunisia, the 345th was no longer part of the 12th Air Force; instead serving with the 15th under Major General Spaatz. Weber continued to work on “Jack Frost”, but helped out on “Shanghai Lils Sister”. A violent storm came across the desert, breaking poles, tearing down some tents and flooding others up to the bottom of the cots. Weber and his men had staked down their shelter with 40mm shell casings and added a floor made from some scavenged wood, leaving their tent fairly dry and intact. The deluge of rain had caused some of the planes to sink in the mud, including “Jack Frost”, which was buried in the muck up to the bottom of its tail. When things dried out, more planes came into the field and Weber and his crew helped on each. “Hulla Girl”, “Duchess”, “S”, “Tangerine” and others joined the B-24s that were “all over, wing tip to tip”.

Another relocation was ordered; this time to Italy. Weber was flown along the coast of Sicily, where he looked down to see a huge convoy of Allied Navy ships. One of the engines on the plane started to smoke, then conked out. At the same time a small fire started in the navigator’s area, and the pilot instructed the crew to put on their chutes. Weber soon realized that there weren’t enough chutes to go around, and was very relieved when they landed unharmed at Brindisi, Italy. It was good to be out of the arid desert, but the camp and airfield was still surrounded by dozens of canvas tents. Right after Weber’s plane landed, a German plane dropped bombs that killed some of the men enroute to the camp and destroyed their trucks.

Weber and his men went back to work as “Jack Frost” began a new series of runs, first to bomb an airfield in Athens, then to Augsburg, Germany, where “Sandman” didn’t come back. The force was increased when the 450th group with brand new green painted B-24s joined the 345th. Weber picked up a small stray dog and named him “Buono”. The little stray helped Ted and the others feel a less homesick in the monotonous and dangerous installation.

Wine seemed to be a cure-all for most of the men when dealing with periods of boredom, the stress of heavy workloads, B-24’s and their crews not returning and German air raids. Nightly drinking bouts and fighting became the norm, especially since wine was readily available in Italy for the right amounts of U.S. dollars or barter. Soldiers often traded issued or purchased cigarettes and tobacco for wine, olives, fruit or cakes from the local merchants when goods were available. December 31 brought a heavy downpour that kept soldiers in their tents, so they drank more heavily than usual and shot off guns around the camp. Later in the spring, Weber was granted a pass and visited the cathedral at Oria, a place he found very strange with its large crypts full of mummified remains on display.

Weber was ordered to D.S. (detached service) and sent to Scan Zano to oversee Italian workers who were building a practice bombing range. After two weeks of this “vacation” he was back at camp in time to see the destruction of “Cielito Lindo” when it crashed during a takeoff.

More orders came through for the squadron to move to a new airbase in Lecce, Italy. Though the men were still living in tents by the airfield, the base had the good fortune of being located next to an old castle that had been converted into a mess hall and chapel for the men.

In addition to being in a different location, a new commanding officer, Colonel Gray, took over the 98th group. On Jan. 28, he had all of the men at the base assemble, dressed in their olive drab uniforms. Weber was furious with the new colonel, who had just come from the U.S., lecturing to him and the other veterans who had been overseas for 19 months. Weber wrote; “This recruit told us, ‘…Look at me, I’m your new C.O. I don’t think you know who I am. A few of you, some of you, all of you, in fact, want to see this war end. It is the responsibility of the ground crews to see that the planes will fly and come back…’” Weber commented that after 10 minutes of this “pointless trivial drooling”, they were dismissed. He was amazed that an officer with “superior intelligence” would take men off the planes, motor pools, etc., get them dressed up, march them around and tell them such “junk”. His final comment was, “Well, what can you expect from a recruit, fresh from the States!”

Shortly after attending to this debacle, Weber received a copy of President Roosevelt’s citation to the 98th group for their performance in the Ploesti raid. In addition, he was assigned to head the crew of a new four-turreted B24J plane, named “Melodie”. The rain returned in earnest with fields drenched and floods in the lower areas, causing equipment and vehicles to be “buried” in the mud. When weather caused missions to be scrubbed, Weber and his comrades would go hunting for wine, fresh vegetables or fruit, often bartering cigarettes for whatever they could find. If the weather was good, the planes carried out a continuing series of missions on a daily basis. Dozens of small flak hits ruptured hydraulic lines and jammed synchronized mechanics. “Snafus” caused by novice airmen added to the minor damages to the aircraft and their armaments. Smaller problems could be quickly repaired, but more major malfunctions totally destroyed many of the planes, and caused numerous casualties to their crews. As “R” was landing, her left landing gear collapsed, flipping the plane over and causing it to break apart; it’s struts, tail and turret laying over the right wing. “Melodie” was grounded for several weeks after coming back from a raid on Ploesti. She had suffered a number of large flak hits along the fuselage, one that drained her wing tank, and others that wounded the co-pilot and blew the camera out of a crewman’s hands while he was taking aerial photos. After this flight, all of the 345th’s planes were out of commission, but with quick repairs, seven were back into the air by the following evening.

Weber, not wanting to lug around his .03 as he worked on the planes, traded in his rifle for a pistol, numbered #51883. He carried it when visiting a buddy at the nearby base at Bari, where they jumped into a slit trench when bombs fell from German aircraft.

Orders came out from the C.O. that the men were to report to the planes whenever the Germans started a bombing attack. Weber wrote that he thought this was rather stupid as “the planes would be the targets!”, putting them all in further harm’s way.

A new bomber named “I”, flew out on its first mission to Wiener Neustadt, and came back riddled with flak holes in its front turret and fuselage. After fast repairs, the plane flew off to a second mission, limping back with holes in the rudder, fuselage and needing an engine replaced. Another B-24 stalled as it attempted a landing, the belly leaving a wide furrow with bomb bay doors, nose wheels, struts and plexiglass scattered in its wake. The bomber snapped in half, killing half the crew and trapping the other half inside the burning wreck. Ground crew men braved the flames and managed to pull the remaining airmen out, but as the fire raged, ammo started going off, and they retreated, letting it burn out. Shortly after, the air raid alert sounded, sending men into the slit trenches when German bombers were sighted in the area.

The new C.O., Colonel Gray, “struck again” when he had the entire force assembled in formation for another speech. He contended the group was having poor bomb plots on their missions. This was to be remedied by having them drill for the next hour in their dress kakis. He also reminded them to always salute when seeing their superiors. Weber was not impressed. His morale was further dampened when he received news that his rotation back to the States was not until August 1945, another 18 months!

Planes continued to crash, either as a result of mechanical failures, or due to overly fatigued crews. One crashed on takeoff, a blown tire causing the aircraft to loop over its left wing and end up a twisted mess. Another overshot the runway and belly landed outside of camp. Weber and a crew were sent out to the wreck to salvage guns and parts to be used as needed replacements.

With the moves into Italy came tighter security measures for the squadron, which was now located in what had been enemy territory. Besides the strict letter censoring that had been enforced since they landed in Africa, men were now ordered to not keep diaries or journals for fear of sensitive information falling into German hands. Weber noted this on one of his final entries in August, 1944, then wrote that he intended to send his diaries home on the next mail haul.

Weber continued to perform his duties as the 345th squadron flew non-stop sorties from the Leece base, attacking targets in France, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania. His unit helped the Soviets in the Balkans and partisans in Yugoslavia and their neighboring countries. By the time Hitler’s war machine collapsed, 417 missions had been flown by the 345th, backed by the hard work of the personnel who “kept them flying”.

Ted Weber completed his tour and left Europe on April 19, 1945. On July 27, he was released from service at Fort Sheridan, Ill., and returned to his civilian life. He would go to college in Madison, Wis., on the GI bill, become a certified public accountant and live outside of Chicago until his death from heart failure in 2003. Though not an “Audie Murphy” combatant, Weber spent 2 years, 9 months and 14 days of service to his country in foreign lands, doing his job well even under trying conditions, with limited resources, and under the constant threat of attack from a desperate enemy. His squadron took part in the Air Offensive Europe, Ploesti Air Raid, Rome Arno, Air Combat Balkans, Southern France, Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Central Europe, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Sicily, Naples, Foggia, No Apennines and the PO Valley.

For his service, Webber was awarded the Distinguished Unit Badge, 1st Bronze Oakleaf Cluster, one service stripe, the Good Conduct Medal, American Theatre Ribbon, Five Overseas Service Bars, and the Europe, African, Middle eastern Ribbon with three silver stars.

If you wish to read the whole story on Ted Weber please click on parts I and II below.

Chris William has been a long-time member of the collecting community, contributor to Military Trader, and author of the book, Third Reich Collectibles: Identification and Price Guide.

"I love to learn new facts about the world wars, and have had the good fortune to know many veterans and collectors over the years."

"Please keep their history alive to pass on to future generations".