A Long Legacy: Collecting relics from the Battle of Gettysburg

The great Battle of Gettysburg was worth commemorating even as it raged and both soldiers and besieged residents of the town took the opportunity to preserve important mementoes of the fight. Many of these early relics formed the basis for some of the largest of the Gettysburg collections. Several of the most significant collections of Gettysburg artifacts were assembled by Gettysburg civilians who witnessed the fight — J. Howard Wert, John Rosensteel and John Spangler.

by William F. Howard

The smoke of battle still filled the air in the fields around the little town of Gettysburg, Pa., when the first relics of the epic battle were collected. Even to the soldiers who had survived the earlier battles of Antietam and Chancellorsville, the three day battle of Gettysburg, fought July 1-3, 1863, was a fight to remember. The Confederate army under the command of General Robert E. Lee had brought war to the North and the invasion had been stopped after a battle that had cost the lives of 5,100 soldiers and more than 50,000 casualties.

The battle had been fought on rolling farm fields and craggy, boulder-strewn hills in southern Pennsylvania. The military campaign that had brought bloody battle to Gettysburg marked the farthest incursion of the Southern army during the Civil War and the Union victory there turned the tide toward the eventual defeat of the Confederacy. The great battle was worth commemorating even as it raged and both soldiers and besieged residents of the town took the opportunity to preserve important mementoes of the fight. Many of these early relics formed the basis for some of the largest of the Gettysburg collections.

Several of the most significant collections of Gettysburg artifacts were assembled by Gettysburg civilians who witnessed the fight — J. Howard Wert, John Rosensteel and John Spangler. Wert, who later served in the 209th Pennsylvania Infantry, included one shell fragment in his collection that he noted was “still hot” when he found it on the battlefield and remarked on the paper tag that he could still hear the sounds of battle in the distance as he wrote.

Another local boy, John King, posed for a tintype photo in 1863 holding a Confederate sword bayonet. The rare bayonet is now owned by a private collector. Two days after the battle, John Rosensteel, then a 16-year-old Gettysburg farm boy, was helping the burial crews on the battlefield when he came upon the body of a Confederate soldier resting beneath a tree. An Eli Whitney rifle musket dated 1859 was lying across the dead soldier’s legs. Rosensteel buried the corpse and kept the musket. The relic became part of the famed Rosensteel collection and is now on display at the National Park Service Museum in Gettysburg. Once privately displayed, Rosensteel’s collection was later purchased by National Park Service.

“All over the field are numerous men from the country, engaged in gathering whatever is of value…. A few are merely in search of relics, but the most of them are bearing away any and everything that they consider of pecuniary value. Here is this orchard I find a country man engaged in cutting the harness from one of the dead battery horses. Another has collected a dozen blankets. Another walks past me with three of the best muskets he can find on the battlefield.”—Thomas W. Knox, New York Herald

Although soldiers continued to collect relics after Gettysburg, some historians have contended that the grinding battles of 1864 and 1865 soured many soldiers on collecting. George Noyes, who served as a Union cavalryman, wrote, “The ground was strewn with the usual relics of a battlefield. A few of these I collected and put into my saddle bags, carefully keeping them until I had personal experience of battle, when I threw them all away, needing no reminders of its scenes of horror and excitement.”

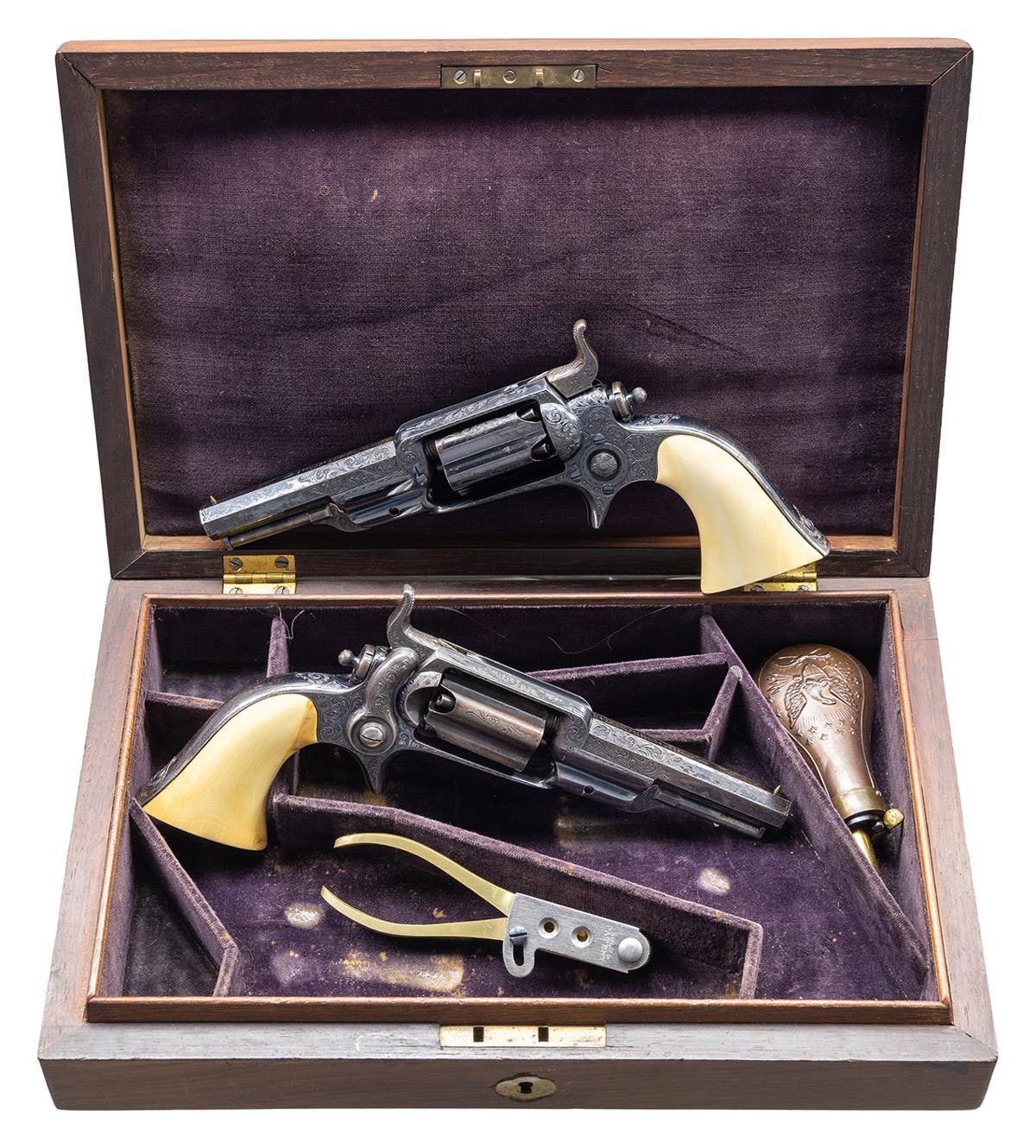

Regardless of such sentiment, relics associated with the battle of Gettysburg were collected more aggressively than the relics of any other battlefield and formed the foundation for some of the great Civil War collections at the turn of the century. Perhaps no collection was greater than that of J. Howard Wert — an assemblage of meticulously tagged artifacts that numbered more than 4,000 items. Included in the collection were such rare items such as Union General Meade’s headquarters flag, the saddle used by General Barlow when he was wounded, a pocket knife used by Lt. Bayard Wilkinson to amputate his own leg during the first day’s battle and several presentation swords carried by leading officers who fought in the battle.

Another Gettysburg resident who amassed a large relic collection was William T. Ziegler, whose farm was located directly in the path of Pickett’s Charge. Ziegler served as a corporal in Company F of the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry until he was captured in battle. He returned home at the end of the war and began compiling a large collection of relics that he picked up from the battlefield and displayed at various veterans events. Ziegler’s collection was purchased by several Gettysburg area militaria dealers in the early 1980s and dispersed. Items from Ziegler’s once impressive collection were sold by The Horse Soldier, G. Craig Caba and George Lower and can often be found on the private market today still bearing labels or receipts from these dealers.

Other large family collections of Gettysburg relics were put together by the Spangler, Trostle, Weikert and Shields families in the years after the war. The Shields Collection was auctioned in 1985. The most recent family collection of Gettysburg relics to come on the market was that of John P. Geiselman. Geiselman, who died in 2001, owned a general store just outside Gettysburg, and assembled a huge collection of artifacts that had been sold by The Horse Soldier.

Collecting Gettysburg Relics Today

Artifacts associated with the Gettysburg battle have always commanded a premium. Modern collectors should be wary in dealing with Gettysburg-attributed items that do not have solid provenance. A cursory scan of Internet trading sites suggests that the “Gettysburg aura” has been applied to many common battlefield relics such as buttons, bullets and assorted brass and iron relics. A standard eagle button worn by a Union soldier will generally sell for about $20 until “Gettysburg” is added to its catalog description, increasing the price to about $40. As a result, it is recommended that collectors purchase Gettysburg items only from respected dealers who stand behind their items and who have earned a reputation of trust. While collectors will likely pay a premium for purchasing from the known dealer community, the preponderance of artifacts on the market that have been attributed to the Gettysburg battlefield without proper documentation requires reliance on the more established dealers.

In 2013, the battle of Gettysburg will mark its 150th anniversary and relics associated with the great battle will likely be in even greater demand. Just a few years before his death, the great Gettysburg collector J. Howard Wert reflected on his collection of relics as the battle was celebrating its 50th anniversary. Wert wrote, “As these lines are penned, from the walls around cartridge box and cap-box, bayonet and sword, canteen and canister; with a hundred other relics gleaned fifty years ago from the fields and woods of Gettysburg, look mutely down upon the write and vividly recall [the] noble stalwart men, some garbed in blue and some in gray, who had bravely fought and had fallen for the flag they followed.”

Even today, collecting Gettysburg relics can bring that spirit and connection back and help collectors and historians establish a link to the soldiers who once waged war at Gettysburg.

The relics of war bear a constant reminder that these were real men, not the creations of novelists or movie makers, who marched, fought and died in the fields made famous by their sacrifice. Collecting Gettysburg artifacts is a way of remembering and honoring that sacrifice.

A GETTYSBURG COLLECTOR’S RESOURCE LIST OF BOOKS

- Robert Jones. Battle of Gettysburg: The Relics, Artifacts & Souvenirs, 2009 (see http://stores.lulu.com/civilwarbooks)

- Mike O’Donnell. Gettysburg Battlefield Relics & Souvenirs. O’Donnell Publications, 2009 (see mike@odonnellpublications.com)

- Steve Sylvia & Mike O’Donnell. The Illustrated History of Civil War Relics. Moss Publications, 1978.

William F. Howard is a military collector and author of numerous books and articles on military topics.