The Spanish Cockade of 1898

Uniform insignia worn during the Spanish American War and Philippines Insurrection

A ‘Bit of Ribbon’ worth fighting for

Napoleon Bonaparte has often been quoted as saying, “A soldier will fight long and hard for a bit of colored ribbon.” For souvenir hungry American soldiers fighting in the Spanish American War the cockade from a Spanish soldier’s straw hat was just such a ribbon.

As the emblem of the Spaniard’s homeland, the cockade symbolized everything for which he fought. Because of its nationalistic symbolism, and because it was small and pretty, it became one of the most prized souvenirs. Men may not have actually died to acquire one, but they certainly did die fighting for, or against, what it represented.

Origins of the Uniform Cockade

Known as an escarapela, a period Spanish source defined the cockade as “... a circular badge, made of folded cloth, worn on the hat as a national distinction.” In one form or another, the cockade had been worn by Spanish soldiers since about 1700. Before the last quarter of the 19th century, it was generally solid red, the color of the ruling House of Bourbon. A Royal Decree of December 2, 1844, established the red cockade as the symbol of the kingdom under Queen Isabella II.

In the late 1860s, political climates began to change rapidly in Spain. Isabella II abdicated in 1868 and was replaced in turn by a provisional government, then King Amadeo I, an imported Italian from the House of Savoy. He was in turn was followed by the short-lived First Republic.

On May 27, 1871, during the reign of Amadeo I, the cockade changed to the colors of the national flag, red and yellow, romantically referred to by Spaniards as sangre y oro or “blood and gold.” Why the King order the change is unclear. Possibly he wanted to affirm his adopted Spanish identity, or perhaps he did not want his reign linked to the former Bourbon monarchs. In any case, the move did not meet with the complete approval of all Spaniards.

Articles published in the conservative newspapers of the day strongly questioned the need to change such a long-standing tradition. The emotion expressed over such a little thing as a badge demonstrated the symbolic importance placed on the cockade by Spanish patriots of all political factions.

Finally, in 1874, the Bourbon family returned to the Spanish throne in the person of King Alfonso XII. Despite the outcry from hard-line monarchists, the red and yellow cockade was retained by the new king and remained in service long past the Spanish American War.

After the colonial era, the cockade would change only once. During the turbulent era of the Second Spanish Republic, (1931-39), the cockade was a tricolor badge of red, yellow, and purple. With the triumph of the Nationalist forces at the end of the Spanish Civil War, the traditional red and yellow cockade returned. It is still worn today.

Not only did the cockade’s appearance change over time, it was also made from many materials and differed in each of the colonies. Examples can be found made of wool cloth or worsted wool tape, silk ribbon, brass, zinc, and leather. A decorative retainer or clip, called a presilla, made of worsted wool or bullion cords, or metal with an embossed pattern is on most cockades. Although in defiance of the regulations, cockades will occasionally be observed with a branch of service insignia, such as a light infantry horn, in place of the button and presilla. Only the artillery was officially allowed its own insignia.

While the cockades most often found among souvenirs are those taken from straw hats, similar insignia, but slightly different in size or construction, will be found on most Spanish military headgear of the period including those affixed to the front of the ros (shako) and teresiana (kepi), and as part of the plates on the sun helmets worn in Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

The Cockade in the Spanish Colonies.

Cuba

The use of a red hat badge by troops stationed in Cuba before 1871 is well-documented in both written accounts and photographs. However, the date it was first adopted is sketchy.

An 1851 description of the first Civil Guard unit in Cuba refers to the shape of the cockade as “squared.” In 1855, the first uniform regulations for the newly organized Institute of Volunteers authorized a red hat insignia. An American author’s 1859 travel account also noted red cockades on the soldier’s straw hats.

The most complete, early description, however, is found in the 1861 infantry uniform regulations for Cuba. In this, the cockade is described as a squared badge of merino wool divided by folds, with a brass regimental number or light infantry horn insignia worn in the center.

The one surviving example of an early cockade that has been observed closely matches this description. The artifact measures 5.5 x 5cm and is made of fine red wool with two sets of three folded welts that separate the center from the sides. It is embroidered in the center with a gold bullion number “2” within a v-shaped wreath, identifying the wearer as an officer of the 2nd Volunteer Battalion of one of the islands major cities like Havana or Santiago. The reverse is stiffened with a thick paper backing.

In Cuba, the new 1871 pattern round cockade displaying the red and yellow national colors is first mentioned in a directive from the Sub-Inspector General of Cuban Volunteers dated January 17, 1872. This order described the appearance of the cockade, which would remain the regulation pattern until the end of the colonial era in 1898, and codified the cord colors for both officers and enlisted men.

Cockades that come with Cuban provenance found among the souvenirs of the Spanish American War match this 1872 directive. Most are made of worsted wool tape or ribbon gathered over a pasteboard disc. They measure approximately 5.5 cm in diameter, but size will vary.

Officer’s cords were made of metallic bullion. For the infantry, artillery, marine infantry and medical service they were gold-toned. Those of the cavalry, engineers, and military administration were silver in color. In addition, officers also displayed their rank in the form of metallic braid, the same as worn on the cuffs of their uniforms, placed horizontally across the face of the cockade.

The enlisted cockades had a worsted wool cord presilla, looped in five or six rows with a button in the center that identified the soldier’s branch of service. The cord colors were red for line infantry, green for light infantry and white for cavalry and engineers. Dark blue was later added for marines. The artillery was not authorized a colored cord and button. In their place, a brass flaming bomb insignia was affixed.

Variant cockades exist, including a “universal” pattern made without the distinguishing colored cords. A scarce, stamped-brass badge with embossed folds and a pin-back attachment has also been documented. The colored finish is painted, and an infantry button is placed at the center.

Civil Guard and Police Cockades

Cockades of the various police organizations in Cuba differ from those of the army and volunteers in both size and construction details. The badge is much larger than the army pattern, 7.5 cm in diameter, and is adorned with woven tape braid in place of the cord presilla.

Three different police cockades from Cuba have been observed. Those worn by the Civil Guard and the Havana Municipal Guard were red and yellow like those of the army while those issued to the Orden Publico are solid red as worn before 1871. Braid retainers were white with a red center stripe for the Civil Guard, blue with a white stripe for the Municipal Guard, and solid yellow for the Orden Publico. All have a small hook on the back end of the braid to allow attachment to the hat’s crown.

In 1881, the wearing of the national cockade by civilians, the salvaguardia and civil public works employees was prohibited in order to avoid them being confused with the Civil Guard.

Puerto Rico

The history and pattern of cockades issued in Puerto Rico generally follow those of Cuba. An 1860s carte de visite (small photograph) taken in San Juan has been observed showing an infantryman with a red square cockade on his hat. The Puerto Rican garrison adopted the 1871 pattern cockade at about the same time when it was introduced in Cuba.

From artifacts observed in the souvenir record, two variations of the round National cockade can be associated with this colony. The first is identical on the obverse to the cockades most commonly issued in Cuba. However, they differ from Cuban examples on the reverse. A two-prong iron wire clip is attached to the back which allows the badge to be added or removed from the hat or sun helmet.

A distinctive cockade was issued to the Volunteers of Puerto Rico with a yellow cord presilla and brass button embossed “Vos DE PUERTO RICO.” Unlike the police cockades of Cuba, those issued in Puerto Rico match the standard 1871-pattern in size and construction. A Civil Guard example with white cord presilla and another from the Municipal Police of San Juan with a denim, blue-colored cord have been noted.

A second style associated with Puerto Rico was made of silk with a button in the center. These survive in relatively large numbers as they were issued to all the members of the 6th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. The unit history notes the following at the time of the regiment’s return to Boston from Puerto Rico:

“Rosettes of ribbon of the Spanish colors, held together by a Spanish infantry button, which had been presented to the men on the boat, held back the campaign hat brims from the sunburned faces of the men.”

Most likely, these were purchased in San Juan from the military goods store “El Ros de Oro” (The Golden Shako). The Spanish cockade remained a badge of honor among the men of this regiment and was incorporated into much of their veteran association’s iconography. All examples of this type of cockade are found without colored cording.

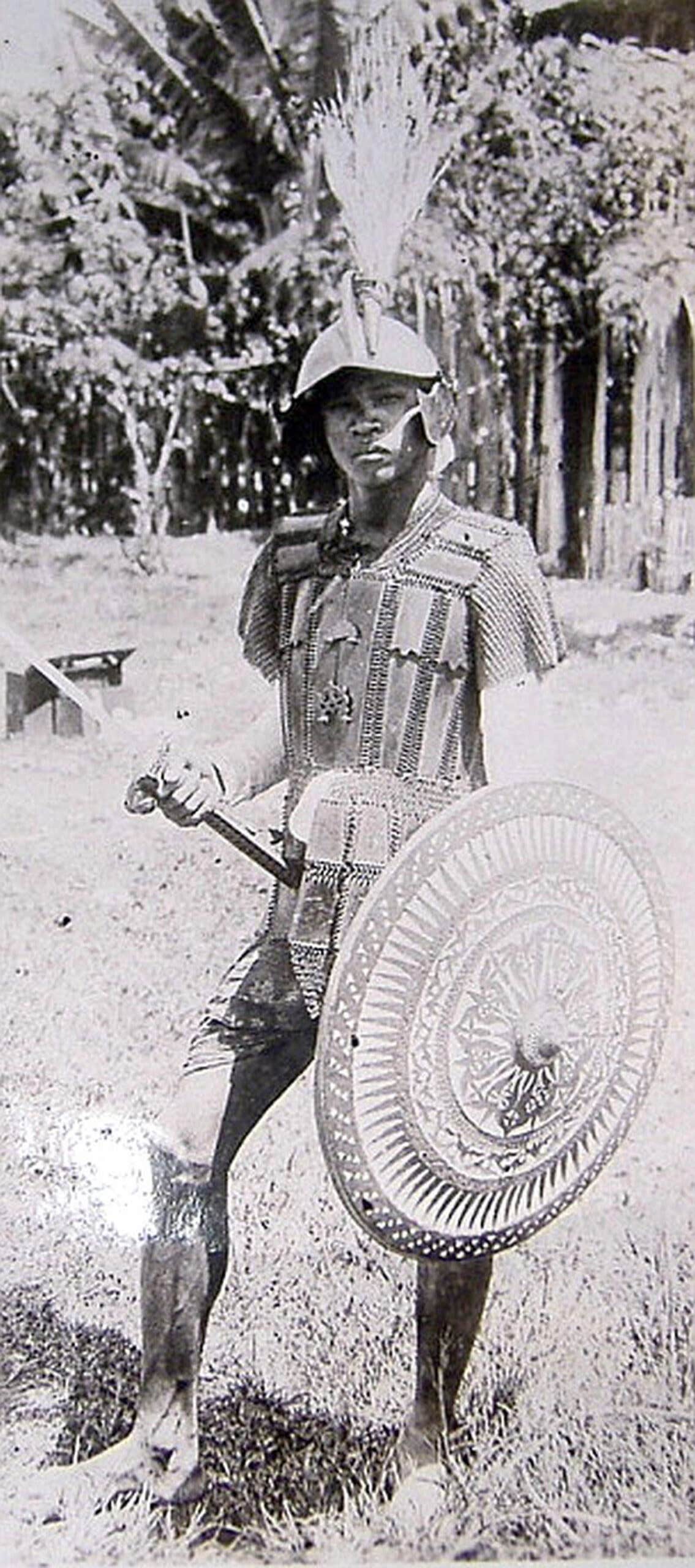

The Philippines

The square red wool cockade as used in Cuba does not appear to have been use in the Philippines. Color illustrations of uniforms worn in the Philippines published in 1855 show round red cockades with metal or colored cord retainers. Modifications to the uniform regulations made in 1861 described the officer’s cockade with bullion cords and rank insignia.

Unlike the cloth cockades issued in Cuba and Puerto Rico, the majority of 1871 pattern cockades with Philippines provenance are made of sheet zinc, stamped in a raised fan pattern and painted in the national colors. In general, they are the same size as the cloth cockades from Cuba. Some are embossed with false cord presillas painted in the branch of service color and a button affixed in the center. One example is known with an applied brass light infantry horn with unit number “14” identifying it to a member of the “Batallón Expedicionario de Cazadores No. 14,” one of the 15 light infantry battalions raised in 1896 for service in the Philippines.

COLLECTING COCKADES TODAY

Among U.S. collectors, cockades from the era of the Spanish American War naturally attract the most interest. Due to their popularity as souvenirs and the post-war purchase of large, un-issued stocks by New York military goods dealer Francis Bannerman, original cockades are not too hard to find. A few can regularly be found at military shows and even more are offered on the on-line auctions.

The more common examples, like those of the line infantry, can often be had for under $100, while other branches may fetch slightly more. Scarcer specimens, such as police and Philippine metal cockades, can command higher premiums, but with patience, even these can be found at reasonable prices. Early square red cockades are difficult to price, as only one is known in an American collection.

You may also enjoy

*As an Amazon Associate, Military Trader / Military Vehicles earns from qualifying purchases.

A prolific author and collector, Bill maintains "The Spanish Colonial Uniform Research Project," an ongoing study of the uniforms and equipment of the Army of Spain during the late colonial period and the Spanish American War, 1868 - 1898. Click here for more info: ¡RAYADILLO!