The history behind the George Cross

England’s George Cross was the royal award reserved for heroes.

On September 24 1940, during a period of WWII known as the “Blitz”, when British cities were being subjected to heavy bombing raids by the German Luftwaffe, King George VI made a radio broadcast from Buckingham Palace in London to announce the institution of two medals in accordance to a Royal Warrant. The broadcast was delivered in three parts, with the first part being used for the king to recap briefly the events of the past year, in which he reminded people:

“Great nations have fallen. The battle, which was at that time so far away that we could only just hear its distant rumblings, is now at our very doors. The armies of invasion are massed across the channel, only 20 miles from our shores. The air fleets of the enemy launch their attacks, day and night, against our cities. We stand in the front line, to champion those liberties and traditions that are our heritage.”

In the second part of the broadcast the king praised the response to the air raid by stating:

“The devotion of these civilian workers, firemen, salvage men, and many others in the face of grave and constant danger has won a new renown for the British name. Those men and women are worthy partners of our armed Forces and our police – of the Navy, once more as so often before our sure shield, and the Merchant Navy, of the Army and the Home Guard, alert and eager to repel any invader, and of the Air Force, whose exploits are the wonder of the world.”

Mention was also made regarding the contributions of those laboring in factories and on the railways, regardless of dangers and the sirens sounding, as was the honor due to those thousands of civilians, who night after night, endured discomfort, hardship and peril in their homes and shelters.

King George VI concluded his broadcast by announcing:

“Many and glorious are the deeds of gallantry done during these perilous but famous days. In order that they should be worthily and promptly recognized, I have decided to create at once a new mark of honor for men and women in all walks of civilian life. I propose to give my name to this new distinction, which will consist of the George Cross, which will rank next to the Victoria Cross and the George Medal for wider distribution”.

On the same day as the broadcast the transcript of the Royal Warrant appeared in full in the London Gazette, issue 35060, the publication in which all announcements concerning the George Cross, including details of the recipients were announce. Six days later, on Sept. 30, the list of the first people to receive the GC was printed in the London Gazette. The list included Lieutenant Robert Davis and sapper George Wylie of the Royal Engineers, who had successfully dealt with an unexploded bomb near St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Another name on the list, and the first recipient of the new award, was that of Thomas Alderson, an Air Raid Precaution, ARP, warden in Bridlington, Yorkshire — a role for which he volunteered on the outbreak of war in September 1939. The town of Bridlington is sited on the Yorkshire coast, making it an easy a target for the Luftwaffe, and indeed was attacked several times throughout August 1940. Emergency personnel, including Thomas Alderson, attended the aftermath of these raids to rescue victims and make safe the area. In three separate incidents, Alderson led his team to rescue at least 17 people who had been buried under rubble by tunnelling to them, despite the risk from further falling masonry. The citation for his award concluded by stating: “… his courage and devotion to duty without the slightest regard for his own safety, he set a fine example to the members of his Rescue Party, and their teamwork is worthy of the highest praise.” After receiving his award, personally presented to him by the king, Alderson was interviewed for a radio broadcast during which this ever-modest man stated the medal was for all those rescue parties who took part in saving so many lives that night.

After Alderson’s award, a further 130 GCs would be made during the war, including the award made to the people of the island of Malta. To date, the GC has only been awarded 416 times in its 84-year history; 401 times to male recipients, 12 times to women and three “collective” presentations to the Island of Malta, the Royal Ulster Constabulary and the British National Health Service. This makes it one of the scarcest British medals presented and almost impossible for a regular collector to obtain an original example. The award can be won more than once, but to date there has never been a double award.

On the extremely rare occasion when a GC is presented at auction the news sets the collecting world abuzz in anticipation. The last time a GC came up for auction was in 2021, when the award presented to Lieutenant Terence Edward Waters of the West Yorkshire Regiment, for his actions during the Korean War, was sold for £280,000 GBP. The last time before that was in 2015, when the GC awarded posthumously to the WWII Special Operations Executive agent Violette Szabó was sold for £260,000 GBP.

These prices put owning a genuine GC outside the scope of all but the wealthiest of collectors, but that does not deter interest in the prestigious award. An alternative for collectors is to consider obtaining a replica to use as an illustration of the award and there are some very high quality reproduction examples available. Likewise, there are replicas of the Victoria Cross to show Britain’s highest military award, but neither of these is intended to fool even the most inexperienced collector. The largest collection of GCs is held in the Imperial War Museum at Lambeth in London, where Lord Ashcroft displays 30 examples, including those awarded to Odette Hallowes and Violette Szabo, along with more than 200 Victoria Crosses.

Noted artist and sculptor Percy Metcalfe, born in 1895, who studied at the Royal College of Art was commissioned to create the design of the George Cross. King George VI took a personal interest in the design and planning of the medal at all stages. Metcalf used a blank silver cross, measuring 45mm equally in both the horizontal and vertical plane, as the basis on which to create the design. The end of the uppermost arm terminates in an eyelet for the suspender ring to attach to the ribbon bar adds another 3mm to its height. The surrounding edges of the cross have a continuous recessed finish to give it the appearance of being framed. Within the four angles forming the cross Metcalfe very cleverly used the initial “G” to enclose the king’s regnal number to create the royal cypher of ‘GVI’ to give a slight arch to the design.

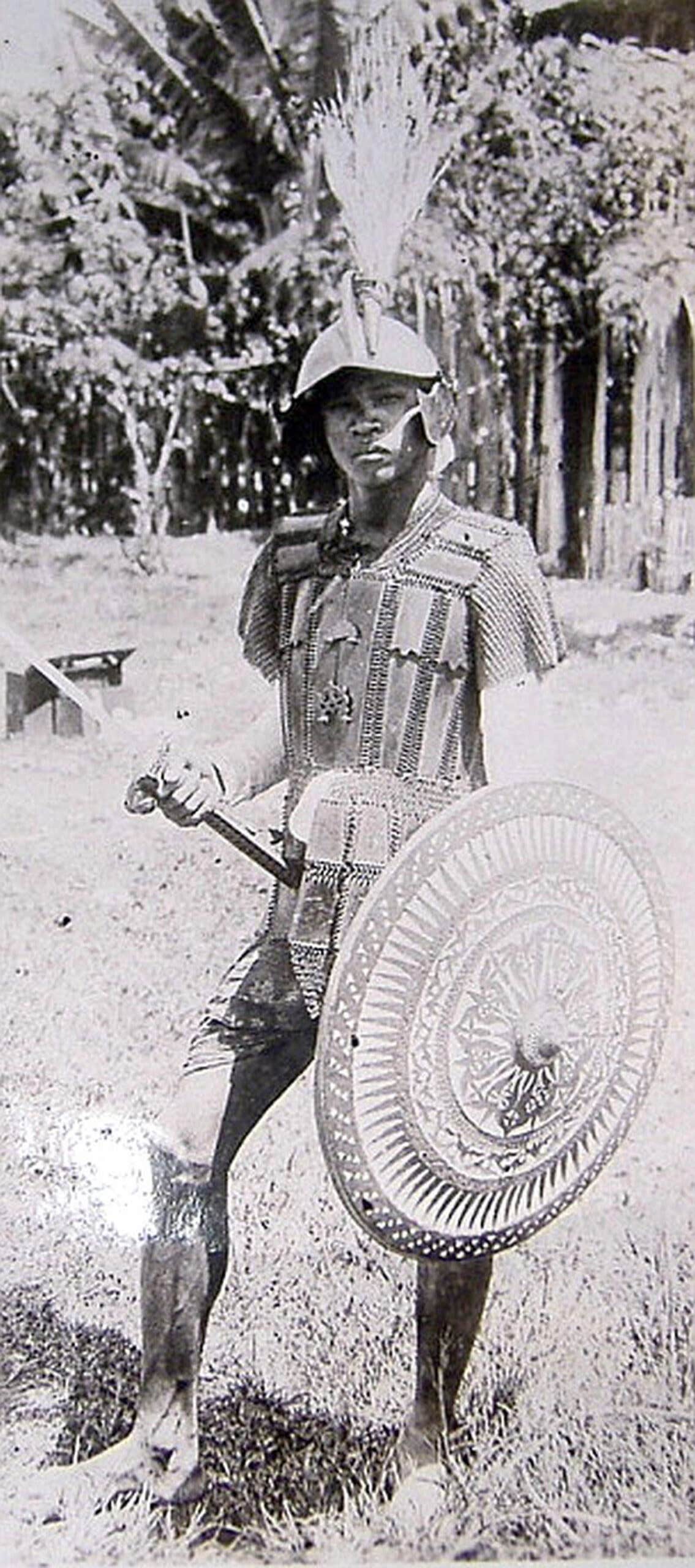

Within the center of the obverse of the cross appears the image of a helmeted mounted male figure, naked except for a flowing cloak billowing out from his shoulders. The image faces to the left to reveal his right profile and represents St. George, the patron saint of England, armed with a Roman-style sword, known as a “spatha” sword, a longer version of the “gladius”, as used by Roman cavalry. The horse is shown in the half rearing position with its front legs rearing over the image of a dragon, whose body lies sprawling under the length of the horse. The rider is holding the sword with the blade pointing downwards and slightly to the rear, poised ready to thrust forward. The horse is fitted with a bridle, held in the rider’s left hand, but there is no saddle, which leaves the rider’s legs to hang freely.

This image, full of patriotic symbolism, is show in relief on a central disc surrounded by a circular double-edged frame within which appears the legend “FOR GALLANTRY” in capital letters. It does not quiet fill the circumference of the circle and the gap in the lower portion is filled with a rosette which has a stud-like feature on either side. The ribbon is “garter blue” in color, after the Order of the Royal Garter, measuring 38mm in width, and passes through the suspender which has a clasp decorated with ten pairs of laurel leaves. The reverse of the award is left completely blank and will only bear the name of the receipt and the date the award was made.

The GC is still awarded, as it always has been, for “…acts of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme danger”. It was meant “for civilians and military personnel when the actions in which they participated would not necessarily be considered eligible for a military award, such as gallantry in the face of the enemy.” Although intended for presentation to civilian recipients throughout the Commonwealth it has been awarded to many members of the military and it has been awarded to both male and female, including a number of posthumous awards. Being second in ranking only to the Victoria Cross, the GC takes precedence over all other awards and decorations. When ribbons only are worn, that of the GC is shown with a miniature example attached. In the event that a second award should be made to an existing recipient, a second miniature GC will be appended to the medal ribbon. Female recipients wear their GC suspended from a garter blue bow pinned on their left shoulder. When only the bow is worn, it is shown with a miniature GC attached. All recipients are allowed to add the initial “GC” after their name on any correspondence.

When John Vereker, 6th Viscount Gort, himself a holder of the Victoria Cross, was appointed to the post of Governor of Malta in 1942, he carried with him the actual GC, which had been conferred on the island when he arrived to take up his position. The island had been bombed mercilessly by German and Italian aircraft in an effort to subdue it and prevent the island’s use as a naval base from where Royal Navy ships could intercept Axis convoys taking supplies to Rommel forces in North Africa. In recognition of the islanders’ fortitude, King George VI awarded the “collective” medal to the island as a whole. A personal letter from George VI, dated April 15, 1942, was handed to the outgoing governor, Lieutenant-General Sir William Dobbie, in which the king expressed how it was: “To honour her brave people, I award the George Cross to the Island Fortress of Malta to bear witness to a heroism and devotion that will long be famous in history.” In response, Sir William answered: “By God’s help Malta will not weaken but will endure until victory is won.”

The emblem of the GC was incorporated into Malta’s national flag in 1943 and even today, 60 years after it was given independence in 1964, the GC still appears proudly in the top left-hand corner of the island’s red and white flag. The actual George Cross and original letter are displayed at the War Museum in Fort Saint Elmo in the island’s capital Valletta.

There are many amazing stories behind the 416 awards. Each is worthy of mention — civilian and military.

For example, 22-year-old, Barbara Harrison was working as a flight attendant on BOAC Flight 712 on April 8, 1968, when a fire broke out. The Boeing 707 was forced to make an emergency landing at Heathrow Airport and Harrison was instrumental in assisting many passengers to safety. Sadly, she succumbed to smoke inhalation and her body was found along with some passengers who she had obviously been helping. Her family will always be proud of the fact Harrison was posthumously awarded the GC on August 8, 1969, in recognition of her bravery.

Twenty years earlier the GC had been awarded to another woman in recognition for her service during WWII. Noor Inayat Khan was born in Moscow in 1914. Her family eventually moved to France, where she became a successful author of children’s books. When France was invaded by Germany in 1940, the family made its way to England, where she enlisted in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, serving under the name of Nora Baker. Speaking fluent French led to her being recruited by F (France) Section of the Special Operations Executive, SOE. After receiving training in radio transmission and given the code name “Madeleine”, Noor was dispatched to France. Unfortunately she was compromised and arrested by German security forces and interrogated. She was sent to Dachau concentration camp and executed on Sept. 13, 1944, having never divulged any information. On April 5, 1949 she was awarded the GC, joining Violette Szabo and Odette Sansom, later Hallowes, among others in the SOE to be awarded the GC.

At the same time he created creating the George Cross, King George VI instituted another award known as the George Medal, to be awarded under similar circumstances to those of the GC. Although sharing a common beginning, the GM was intended for wider distribution. More than 2,000 awards of the GM made to date; it has its own list of recipients and history.

The GC replaced the Empire Gallantry Medal, which had been instituted in 1922, and recipients holding this award were invited to have them replaced by the GC. At the time of the announcement there were 70 holders of the EGM, of which 59 elected to make the change to the GC.

The most recent GC to be awarded was another “collective” presentation made on July 5, 2021 to the British National Health Service as a whole to all staff members in recognition for services rendered during the pandemic outbreak of Covid-19. The GC will continue to be awarded for various services and, being one of those unusual British medals not to bear the image of the reigning monarch on the obverse, its design will never need to be altered. In that respect it will continue in the same way it always has.