Five Tips From An (Olive) Green Grocer

“If one more dealer calls and complains about the ‘state of the hobby,’ I think my head my explode,” I replied to my Dad when he inquired about the magazines….

“If one more dealer calls and complains about the ‘state of the hobby,’ I think my head my explode,” I replied to my Dad when he inquired about the magazines. “What’s going on?” he asked. “Did people stop liking military history?” That made me laugh. “No Dad,” I said through a smile, “They haven’t stopped liking history.” “Well then,” he concluded, “The problem’s not with the customers.”

That evening, I recounted our conversation to my partner. She asked, “Well what did you Dad mean by that?” I rolled my eyes, “It’s simple… those who say they are 'in the militaria business' really aren’t business people!” My partner rarely takes my side of things, especially when I act self-righteous, so it was no surprise when she fired back, “Well have you shared ideas with them? Not everyone grew up in a small, family-owned business.” Crap. She was right. Even though I tire of hearing about “how tough” times are, I really should try to share some ideas to jump start slow sales.

Now bear in mind, any advice I might offer is worth the price paid… I have no formal business training, I run a very cautious small business “on the side” (much like many militaria dealers), and derive any experience from the only business for which I was solely responsible: Our family’s store during a three-year period when I was 12-15 years old. My Dad’s heart attack prematurely catapulted me into the position of the store’s “manager.”

Though I didn’t realize it at the time, Dad brags how I ran the store for those three years. I just did what I knew how to do: Order groceries, pay the bills and payroll, and make up the weekly ads for the local newspaper. All of this was done under Dad’s supervision, though he was bed-ridden. At the end of each business day, I would sit on the edge of his bed and review everything with him.

All that said, I was not a “natural” when it came to business. I made lotsof mistakes. For example, when our warehouse placed a “super sale” on Minestrone soup, I bought several cases. When I told Dad about my “smart” buy, he asked, “How many cans of minestrone soup have we sold this past year?” I instantly recognized my mistake… the local demand for this esoteric Campbell’s soup was about 2 cans a year.

Lesson 1. Don’t Allow a Bad Investment To Become an Anchor

From that simple soup debacle, however, emerged the first lesson that can equally apply to militaria. Though I had ordered 4 cases of the soup (about 100 cans), I still had to get rid of them. Dad explained to me: If you have a heavy supply of a single item, it costs money to keep it on hand—especially if the item is a slow mover.

I dumped a case of the soup in a round display basket and hung a “special” sign on it. I priced the soup at five cents less than the shelf price. Over the next two weeks, I sold about 3 cans of unwanted soup.

After a month, I asked Dad what I should do about the four cases of soup. My “sale” really didn’t move them.

He told me, “They are dead weight—blow them out.” I marked them down to a “nickel a can” (if I remember, the shelf price was about thirty-nine cents). Within a few weeks, the display basket was empty. My soup debacle was over.

The lesson? If you discover you made a bad acquisition, it is better to take a loss and move it out—fast! For example, if you bought an unissued stack of left-hand GI gloves (or Pederson device pouches, or right-side MRAP mirrors, etc), you are better off moving them out at a loss rather than become known as the guy who totes around a box of left-handed gloves from show to show. The space, time, and—quite honestly—the negative impact they have on your overall display is not worth the money you might get if you keep dragging them around for the next ten years.

Lesson 2. The Customer Is (usually) Right

Dad often reminds me of the day that a good customer bought a case of fresh peaches, only to return several days later demanding a refund for the “10 that had spoiled.” He will say, “Remember when you called and asked, ‘What should I do?’” Yes, I remember the story well. Without hesitation, Dad told me, “Give her a refund and offer her 10 free peaches.” I hated that advice, but I did as I was told.

It wasn’t until many years later, when I finally understood his advice. It became obvious one day as I was writing catalog descriptions at a prominent dealer’s office. I overhead a phone conversation during which I heard the dealer say, “By all means, I am sending you a check today. You can just keep the item.”

What had just happened? I stopped to pry into what was really not any of my business. The dealer explained, “That person is a very good customer—he might spend several thousand every month. Am I going to bicker over an item that cost him a couple of hundred? Heck no!” Just like my Dad and those peaches, the dealer knew the value of customer service. Dad always said, “It’s far cheaper to keep the customers we have than it is to replace them.”

Lesson 3. “Bad Sales are due to Bad Marketing”

The second year when Dad was out of commission was right in the middle of the “energy crisis.” Even though we felt groceries were a “recession-proof” commodity, we saw a huge drop in sales. With a family of seven, Dad couldn’t mope around saying, “Oh business is bad,” or “What’s wrong with everyone? Why aren’t they buying as much as they used to?” Just like the question about military history that he posed to me, he had to recompose himself and answer his own question, “Did people lose interest in eating?”

As with the viability of enthusiasm for military history, interest in eating rarely subsides. If our grocery store wasn’t selling as much food as we had in previous years, something was wrong with the way we were doing business. To find the solution, we had to take a hard look at our own methods.

First, we discovered a new convenience store had opened. Competition always will divert customers. But what did we do anything to counteract that? The answer will be revealed in “Lesson 4,” below.

Second, if supply had stayed the same, but demand had dropped off, the solution was simple (I learned this later in Economics 101): We had to lower the price on the supply.

I can’t begin to recount how many dealers have complained to me at shows about “bad sales.” Each time they do, I pick up any piece on their table and ask them, “How long have you had this item?” Nine out of ten times, the answer will be, “A couple of years.” And then I ask, “What was the price when you first put it on your table?” Again, nine out of ten times, they will reply something to the effect of, “Whatever the price is on that tag.”

This goes back to the soup example, but also applies if it is a quality product like a GP speedometer or a fixed loop camouflaged M1 helmet. If you have carried the item around for a couple of years, and it hasn’t sold, mark down the price! You are far better off getting money back into your hands that you can reinvest in products that you can, hopefully, sell faster and turn a profit.

As a customer at shows, if I walk past a table and recognize the same items from a year earlier, chances are I won’t stop. Nothing says, “Over-priced” like seeing the same thing on your table year after year.

Lesson 4. Loss-Leaders make Profits.

You have heard the term, but do you know what “loss-leader” means? Allow me to make another grocery store example.

You will probably remember how meat was always in the back of your local grocery store. That’s because it was the store’s loss-leader. Meat prices have always been “close to the bone.” That is, there is little, if any mark-up on meat. When we ran a special on hamburger, we generally priced it at about five cents lessthan we paid for it. That is, for every three pounds of hamburger we sold, we lost fifteen cents. And yet, the weeks during which we ran hamburger on sale were the weeks when we made the most money.

The hamburger, located in the back of the store, was the “loss-leader.” Customers came to our store with the intention of buying that “really cheap burger.” On their way to the meat case, however, they remembered they needed buns, ketchup, chips, and charcoal—all items that were not on sale. Losing 15 cents on the burger was quickly recouped by the extras people bought.

In this day of print advertising and online sales, militaria and parts dealers have to learn this simple lesson. If you want customers to look at your ad or visit your website, you better entice them.

Sales (I mean realsales, not paltry “10% off”) are good ways to get readers’ and viewers’ attention. Personally, nothing grabs my attention more these days than “Free Shipping.” I hate buying a helmet for $125 only to find the dealer is going to charge me $20 for shipping. It’s stupid, I know, but I have cancelled purchases because I thought the “shipping was too much.”

More and more dealers are figuring this out and offering free shipping. They use the “free shipping” as their loss leader. I admit, I tend to buy more than I originally intended, if the seller is offering “free shipping.”

Of course, anything can be a loss-leader, but it has to resonate with the customer. You must offer something that you know people will appreciate. Offering a “Free left-handed Glove with every purchase” probably isn’t going to generate as much business as, “Free Calendar with every $25 purchase” or something else along a more useful or rewarding line.

Which brings up another aspect of the loss leader: The best way to generate business is with sale items. Why does the Sunday paper remain the most popular print product in this day and age of computer advertising? Because of the weekly sales!

Big box stores like Best Buy, Lowes, Target, and Wal-mart all have figured this out, and yet, most militaria dealers seem oblivious: Sale items generate sales.

You can’t mark all of your items at full retail and sit around griping because no one is buying. This is militaria! If there was one item made, there were thousands of them made. That means, you probably don’t have a monopoly on the product. If it doesn’t sell, it’s because it is priced wrong.

For example, when I put my house up for sale in 2008, I was worried it wouldn’t sell. My best buddy told me, “EVERYTHING sells… you just have to find the price that a customer is willing to pay.” He was right.

After two weeks on the market, I dropped the price (below what I had paid), and it sold. Three months later, the “housing bubble burst” and no houses were selling. I dodged a bullet by lowering my price, but it gave me a LOT of money in my pocket to reinvest. Had I “held out for my price,” I would have been in a far worse state of affairs after the housing market crashed. Sometimes, taking a loss can save you a lot of money.

Lesson 5: Staying in Business Requires a Two-Prong Attack

Thirty-five years ago, I drew up a strategy to reach a new base of customers for our grocery store. Finally, after I reported the days’ activities to Dad, he asked, “Anything else?”

I took out my notebook, opened it to the pages where I had drawn our meat case and divided into sections that I labeled, “Hams/ Chicken/ Beef/ Burger/ Pork / Kosher.” Without any introduction, I showed it to Dad.

He looked it over, and then finally said, “What’s this kosher section? That’s where we have lunch meat.” He had taken my bait!

Now animated with excitement, I explained how we could reach "a whole new audience,"’ if we put in a line of kosher foods. I showed him how we could do it by moving the lunch meat to the cheese section and reducing the pork section by one fourth.

He listened as I went on with my strategy that even involved the costs for putting in the kosher foods. Finally, when I stopped talking and looked at my drawing with satisfaction, Dad carefully asked, “How many people live in our town?” Confused by the question, I answered, “1,200.”

He probed a bit further, “How many of them do you suppose are Jewish?” I had a great plan, but never considered that out of 1,200 people, in our little Minnesota town, not a single person professed Judaism as his or her faith. I had a good plan, but it was the wrong place.

Okay, I felt pretty stupid, but Dad didn’t point out the futility of my plan. Rather, he explained, “We always have to take care of the customers we have. They might not like seeing their choice of pork reduced. On the other hand, you recognized something very, very important: You always need to be looking for new customers.”

It was easy to feel customer attrition in a small town. If someone died or moved away, that played out on the weekly receipts pretty quickly. The same is true in our hobby.

Every week, dealers complain to me about “the graying of the hobby.” So much so, I am getting pretty tired of this type of moaning. Where I used to just shrug and say, “Yeah, we are all getting old…” I now rebut, “And what are you doing to counteract that?” I get the impression a lot of dealers are waiting for someone else to do something about it.

You would be surprised how many in our hobby don’t use computers. It is a simple reflection of demographics rather than some underground movement to deny technology. Our hobby tends to be attractive to people with disposable income. Those people tend to be older, and older people tend to be less technology-friendly. Yes, those are vast, broad-brush statements, and I am sure you or someone you know is the antithesis to the remarks, but when viewed statistically, that is how the numbers play out.

In fact, for every military history enthusiast who doesn’t use a computer, there is another person out there discovering the breadth of material available online. No judgment here: The dollars in either of those customers’ pockets are equally valuable. Both customers will spend those dollars, so what do you do to make sure they spend it with your business?

Your marketing has to be two-pronged. First, you need to figure out how you are going to market to the online customers as well as those non-computer users. Second, just like my Dad advised me thirty-five years ago, “Not only do you need to keep the customers you have, you need to always be growing your base.”

To that first point—and here is where you get myadvertising—Military Trader and Military Vehicles offers a large palette of advertising options that reaches both audiences. Nick, our “advertising man on point” doesn’t want to sell you a single ad—I know from my own experience, those usually fall flat. Rather, we want to make custom programs to get your business out there. Seriously. You are not too small to advertise nor too large that you don’t need to.

When sales are flat, or even bad, nothing is more obvious then, “You need to look at how you are trying to convince customers to spend their money with you.” You might think Nick reminds you of Herb Tarleck on WKRP in Cincinnati, or that I act like Peabody’s Sherman, but we are committed to helping your business survive. We both know, that without your militaria businesses, there is no hobby.

And the lesson of the second point about keeping current customers happy while simultaneously working to replace customer attrition, is to stay active in the hobby. Give back. All sales aren’t made in dollars and cents. If people see you putting on public displays, giving evening lectures, participating in or sponsoring veterans’ activities, or any other way you can give back, this will pay off in the long run. Keeping your name in front of the public is crucial to survival.

I have a friend who regularly volunteers to Public Television’s “Road Show.” It is very expensive for him to travel to the show and give his time. Nevertheless, it has paid off immensely. He has received a number of calls after appearances—many of which have led to significant acquisitions. He gives to the hobby, and the hobby has rewarded him.

Another buddy drives his fleet of historic military vehicles to local parades in a four-county area. It costs a lot for him to maintain the vehicles and pay for the gas. But, when someone finds a half-track in a field or a jeep in the barn, they call him, because someone they know had seen his trucks in a parade.

Serving the Hobby: Our Number One Goal

While driving to see my Dad this past weekend, I heard a local radio station announce, “Our advertisers’ success is our number one goal.” That made me think.

I asked Nick, our advertising “man-on-point,” if that same philosophy applied to us. “Of course,” he said in his Minnesota-accent, “You betchya!” I figured that would be his response; his job depends on selling ads.

But what about me, the editor of these two magazines? Shouldn’t my commitment be to the readers?

I posed the question to Dad. He thought for a minute and then carefully stated, “By keeping your readers excited about their collecting passion, you areserving the advertisers. If the readers aren’t excited, they aren’t going to buy. If they don’t buy, your advertisers will lose their desire to keep trying. Then, it all begins to fall apart.” He concluded, “I don’t see how you can divide the two groups from each other—they are all your customers, and because of that, they are the most important people in your business!”

I guess, with that, thirty years after I had last worked in his grocery store, Dad gave me another “business lesson:”

Lesson No. 6. Customers are the most important people to our business.

Promote the hobby to Preserve the History,

John Adams-Graf

Editor, Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine

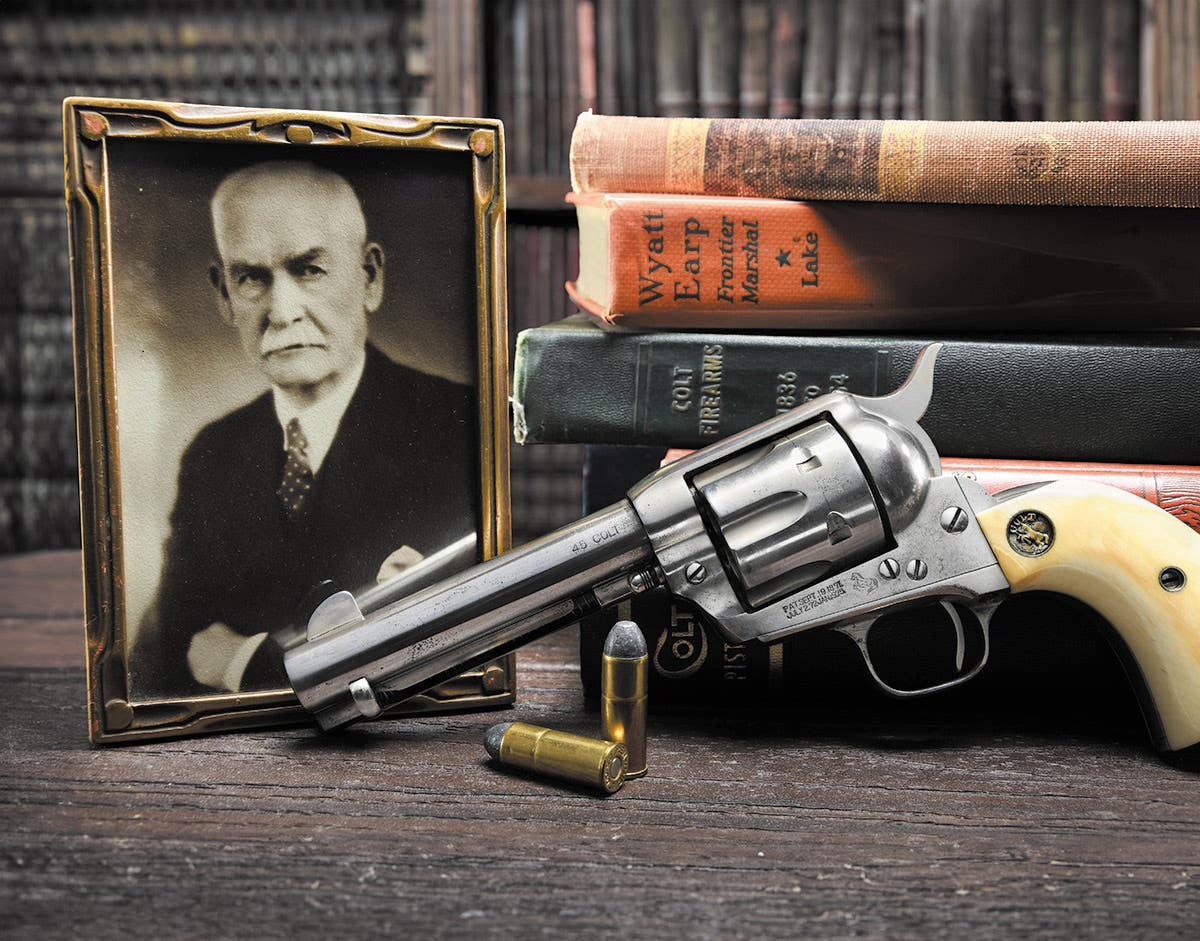

John Adams-Graf ("JAG" to most) is the editor of Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine. He has been a military collector for his entire life. The son of a WWII veteran, his writings carry many lessons from the Greatest Generation. JAG has authored several books, including multiple editions of Warman's WWII Collectibles, Civil War Collectibles, and the Standard Catalog of Civil War Firearms. He is a passionate shooter, wood-splitter, kayaker, and WWI AEF Tank Corps collector.