Behind the ‘Force’: A history of insignia and regalia of the Army Special Forces

The origins of a post-WWII Special Forces in the U.S. Army stems from many sources. However, the concept behind the insignia largely stems from that of the Service Force (1stSSF).

The origins of a post-World War II Special Forces in the U.S. Army stems from many sources. However, the concept behind the insignia and various other regalia largely stems from that of the 1st Special Service Force (1stSSF).

The “Force” as it became known, was an international task force created out of a British Combined Operations Headquarters scheme that emerged in 1942 and dubbed “Snow Plough”. The Operations Division at the U.S. War Department in Washington, D.C. referred to it as the Plough Project or just Plough. It put Lieutenant Colonel Robert Tryon Frederick in charge of overseeing the American aspect of the scheme. It primarily involved the development of what Prime Minister Winston Churchill referred to as a snow tank (T-15 and M-29 Weasel). The tanks, and the men chosen to drive in them, were intended to operate in Norway over the winter of 1942-43.

The 1st SSF was activated on July 9, 1942 at Fort William Henry Harrison, Mont. In addition to his other duties, Frederick was made commanding officer and immediately began structuring the organization of the Force around the snow tank. This produced results similar to the “A” teams that emerged out of the post-World War II U.S. Army Special Forces. The idea was to either drop the Force from the air by parachute and gliders, or land them by sea.

However, after it was determined that an attack on Norway was not possible, Combined Operations and the Combined Chiefs of Staff handed Special Forces over to the U.S. War Department for use as a commando organization. Frederick once again restructured the organization and training of the Force to spearhead attacks and invasions in the Northern Pacific and European theater of Operations. The Force was disbanded over December and January 1945.

However, the original Force was not the only organization created during World War II that would directly influence the creation of a post-war US Army Special Forces capability. To a much lesser extent, Britain’s largely covert para-military organization Special Operations Executive (SOE) offered a strictly overt military organization of international teams known as Jedburgh to liaise with, and add firepower to resistance forces before, during and after the landings in France. Although these teams included Americans from the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the greatest influence actually came from those who led the Filipino guerilla forces, served with Merrill’s Marauders (5307th Composite Unit) or with OSS Detachments in Asia and the Pacific.

With most of France liberated by October 1944 and the Soviet Union steadily advancing towards Germany, the inevitable conclusion of the war was in sight. The Japanese had been militarily defeated, and the dropping of the atom bombs eventually marked the end of that war.

Almost immediately a so-called “Cold War’ broke out between the Capitalist West and the Communist East. In March 1946, Churchill talked of an “iron curtain” descending on Europe as if he had never noticed it dangling there since his days as an anti-Communist during the Russian Revolution. Mainstream academia will have us believe that it was a complete surprise to the Western Allied leaders that roughly 1/3 of the planet’s population had miraculously come under the heel of totalitarian Communism.

Remember the Atlantic Charter? Although not a binding agreement, Churchill and President Roosevelt sought way back in 1942 to assure the global population that the Allies, including the Soviet Union, were fighting WWII to defeat National Socialism, Fascism and Militarism in order to permit the people of the world to democratically choose their own system of government and their leaders. Needless to say, the actions of all involved made the document null and void before the ink on it had a chance to dry.

In reality, Soviets were never post-war allies with the U.S. At first they understood that the West needed them just as much as they needed the West. It is still not absolutely certain whether Stalin played Churchill and Roosevelt like a fiddle or if they, to some extent, allowed themselves to be played. Regardless, by the end of 1943, Stalin began to feel confident that he would not be deterred from biting off as much of Europe as he wanted.

As for Asia, a similar plot had also been laid out in 1943. George Crocker, the author of Roosevelt’s Road to Russia published in 1959, concluded that “In the light of our present knowledge, the course which Roosevelt followed in China policy after the Casablanca Conference of January 1943, seems incompatible with any conceivable pattern of American self-interest or even of plain common sense. It is the common practice of writers to blame General George C. Marshall and his 1945-46 “Mission” for the master blunders which opened China to Communism. Without exonerating Marshall in the slightest, it is only fair to point out that he was simply following the China line which Roosevelt had prescribed as early as 1943.” Everything in Asia rolls downhill from there.

Stalin was not completely happy with his spoils from the war, and in the February 1948 coup d’état in Czechoslovakia President Truman was forced to to react with his Truman Doctrine. The result on April 4, 1949 was the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). This Western Allied creation of a global Communist Frankenstein’s monster that ushered in the need for a new Special Forces capability in the United States Army.

was in command of the Psychological Warfare Center. Ken Joyce

This new Force would emerge out of efforts by General Dwight D. Eisenhower during WWII to establish a Political Warfare Division within his Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). The officer Eisenhower chose to take command was Brigadier-General Robert A. McClure. After the war it was McClure who continued to see a vital need to maintain a psychological and unconventional warfare capability. He was then made the Psychological Warfare Chief in Washington.

As chief, McClure established the Psychological Warfare Department of the Army General Ground School in 1950 at Fort Riley, Kan. Shortly after, in 1952, McClure moved the school to Fort Bragg. There, in May, he established the Psychological Warfare Center and set up a board with a special mission to “…conduct individual training and supervise unit training in Psychological Warfare and Special Forces Operations; to develop and test Psychological Warfare and Special Forces doctrine, procedures, tactics, and techniques; to test and evaluate equipment employed in Psychological warfare and Special Forces Operations.”

Officer of the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne). Ken Joyce

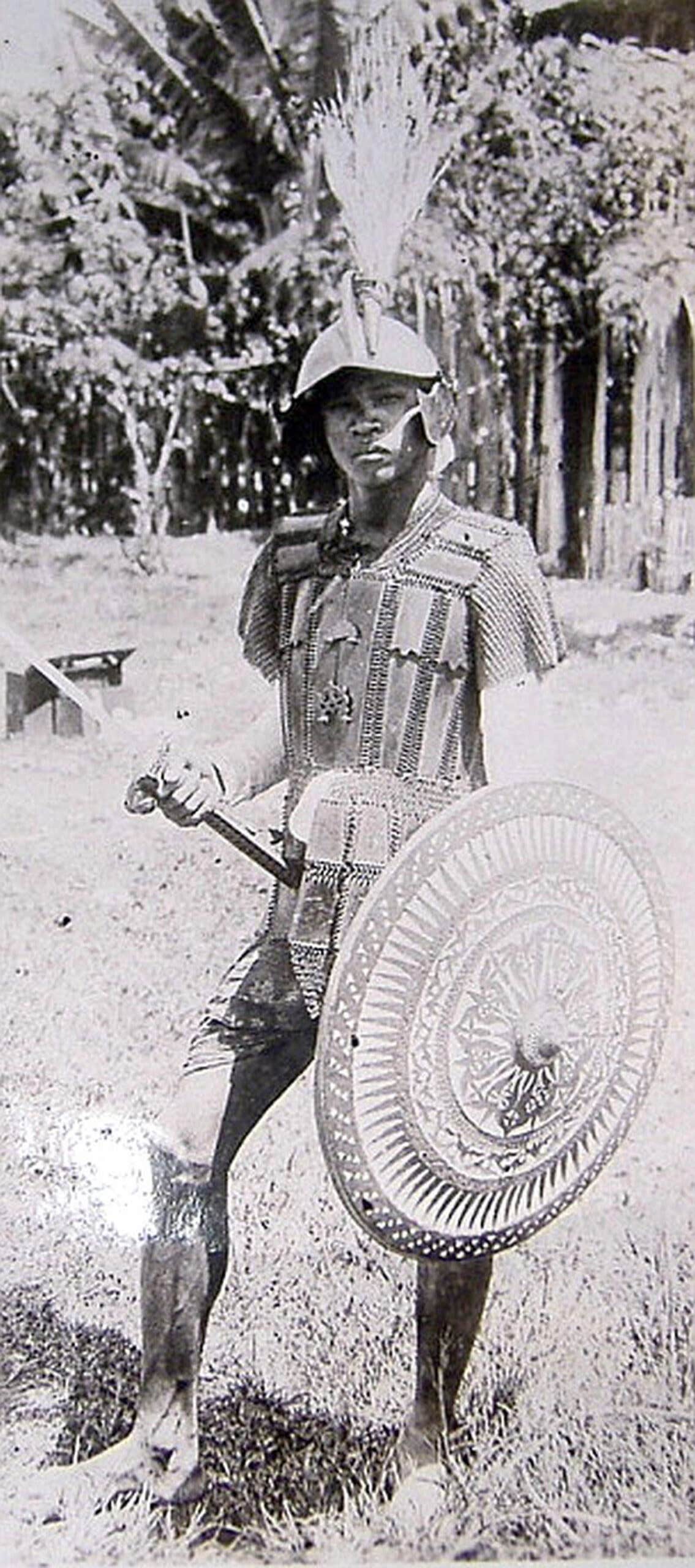

The board included Colonel Aaron Bank, Colonel Melvin Blair, Lieutenant Colonel Martin Waters, Colonel Wendell Fertig and Colonel Russ Volckmann. The main influence behind a future U.S. Army Special Forces capability largely derives from men who were active in the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign. While Bank was a Jedburgh veteran of the European theater of war, he also had experience in Laos. Both Blair and Waters served in the OSS in the China/Burma/India Theater with Waters also serving with Merrill’s Marauders. Both Fertig and Volckmann were Filipino guerilla leaders.

In order to begin their tests and evaluations, the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) (10th SFG(A)) was activated on June 11, 1952 under the command of Colonel Bank at Fort Bragg. Like the Jedburgh and Colonel Frederick’s early organization of the 1st SSF, the 10th Group was similarly formed into small teams. This was the “A” Team concept.

Colonel Bank recruited those like himself and his colleagues, including ex-Airborne, Ranger, and Lodge-Philbin Act soldiers. The Lodge-Philbin Act permitted the recruitment of men in the U.S. Army who had fled from nations engulfed by communism or who had been made stateless at the end of World War II. Their knowledge of target nations and their ability to speak the language meant that these men were invaluable. This type of recruiting quickly expanded to include men from Central/South America and Asia.

With the creation of NATO, the Soviets continued to make belligerent noises from their puppet state, the German Democratic Republic (GDR). They began to contemplate a future conflict against this alliance that had centered a significant portion of its military strength in West Germany/Federal Republic of Germany (FRG).

As tensions heightened in Europe, Stalin’s puppet in North Korea, Kim Il Sung sparked a war with South Korea in June 1950. It marked the first use of the fledgling U.S. Special Forces in Asia after the 10th Group sent a detachment to South Korea in 1953 to work with North Korean Partisans under a special Guerilla Command. A cease fire was finalized in July, and a Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) was created dividing the two Koreas.

As things went global, the assets of the 10th Group were split, resulting in the activation of the 77th SFG (A) on September 22, 1953 at Fort Bragg. Subsequently, on Nov. 22, the 10th Group was shipped to Bad Tölz and Lenggries in the FRG. At Bad Tölz they turned a former Waffen SS barracks known as Flint Kaserne into a headquarters.

With Soviet control over the GDR, Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland and Romania assured, Stalin created the Warsaw Pact in 1955 to counter NATO. Shortly after, things began to get complicated in Vietnam. The first U.S. advisors of the Military Assistance and Advisory Group Vietnam (MAAGV) had arrived in the South or Republic of Vietnam (RVN) in 1955. To accommodate the need for more Special Forces personnel, the following year the Psychological Warfare Center was renamed US Army Center for Special Warfare/US Army Special Warfare School. This was partly because in the latter 1950s the 10th Group had to peel off men to operate in Korea as well as in Vietnam. The need for men in the Asia-Pacific Theater prompted an order on June 24, 1957 for the 77th Group to send four of their detachments to Fort Buckner on the Japanese Island of Okinawa to activate the 1st SFG (A). Covert members of the 1st and 77th Groups were secretly deployed to Laos under Project HOTFOOT in 1959 to train un-uniformed members of the Royal Lao Army in counter-insurgency operations against the Communists.

With things rapidly expanding, a centralized Special Forces Command was activated as the 1st Special Forces Regiment on April 15, 1960 under the Combat Arms Regimental System. A month later, on May 20, 1960, the 77th Group was re-designated the 7th SFG (A). On September 21, 1961, the 5th SFG (A) was activated at Fort Bragg. On April 1, 1963 the 8th Group was formed and, exactly a month later the 6th Group was created, followed by the 3rd Group on December 5.

Other active duty groups included 4, 14, 15, 18, 22 and 23 Groups along with 2, 9, 11, 12, 13, 17 and 24 Reserve Groups and 16, 19, 20 and 21 National Guard Groups. However, many were undermanned and most were dissolved by 1966. Those that remain today are the active duty 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10 Groups with 19, 20 Groups representing the National Guard.

The growing Communist Viet Minh insurgency in what was Indochina during the early 1960s that largely shaped and defined the early history of U.S. Army Special Forces. Unfortunately for U.S. politicians and their accepted policy of containment, the DRV shared a border with Communist China. They also sat atop thousands of kilometers of unpatrolled borders with the RVN. When the U.S. got involved in Vietnam, the Viet Minh and their military wing the Viet Cong already had the Sihanouk and Ho Chi Minh (Annamite Range Trail) supply lines running through Laos and Cambodia to the RVN.

In November of 1961, the proposed role of U.S. Army Special Forces in the RVN mostly hinged on a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) plan to train the indigenous people of the Central Highlands to defend themselves against a growing Communist insurgency as part of the Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) scheme. MAAGV then became the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) in 1962.

In January 1964 the Joint Chiefs of Staff created a top secret subsidiary command of MACV known as Military Assistance Command Vietnam Studies & Observations Group or MACV-SOG. It combined the CIA with special organizations from all branches of the service, including Navy SEALs and Marine reconnaissance units. It is claimed that they had a direct hand in orchestrating the Gulf of Tonkin Incident.

President Lyndon B. Johnson used this incident to seek congressional approval for direct U.S. involvement in Vietnam. After getting his wish, the 5th Group was assigned in October 1964 to take over all U.S. Army Special Forces operations in Vietnam. With conventional forces deployed in 1965, the 5th Group was tasked in June to create the Mobile Strike Force Command or MIKE Force. It was their job to build and defend fortified outposts/camps in combination with the CIDG program.

or MIKE Force SSI, or pocket patch. Ken Joyce

As the Vietnam War intensified, so did incidents along the DMZ in Korea. At the end of 1965, U.S. Special Operations Command Korea tasked members of Army Special Forces to create the Advanced Combat Training Academy (ACTA) near the DMZ at Camp Sitman. They trained members of the US 2nd Infantry Division in counter-insurgency and counter-infiltration tactics. They became known as the Imjin Scouts. 17.

With regard to the Caribbean, Central and South America, after the Batista regime fell in Cuba in 1959 and was replaced by Castro, the 8th SFG (A) was established in 1963 at Fort Gulick, Panama Canal Zone. It was their job to curb a growing Communist insurgency in Latin America. They established a Mobile Training Team that was deployed in 1967 to Bolivia to train their Rangers to deal with a Cuban-backed insurgency. On Oct. 9, the Bolivian 2nd Ranger Battalion captured and killed Argentine Marxist terrorist Che Guevara.

Although President Richard Nixon took the heat for Johnson’s bloody fiasco in Vietnam, signing the Paris Peace Accord in 1973, the 5th group had begun winding down operations back in April 1970. They were completely withdrawn by March 1971.

No doubt many U.S. Army Special Forces Vietnam veterans were upset by their government’s betrayal of their motto DE OPPRESSO LIBER, which roughly translated means TO FREE THE OPPRESSED. However, despite the impossible circumstances under which they operated, a situation as much the fault of the U.S. government as it was the enemy, they were still able to accomplish what they had been sent to Vietnam to achieve. They were able to hold back and defeat a communist insurgency up until the time Nixon was forced to pull the plug.

{Editors Note: This is the first of a three-part series from author Ken Joyce detailing the history and collectibles from U.S. Special Forces}.